Agile as a buzzword has been humming around the corporate world for nearly 15 years. What management board would not want to be seen as quick, nimble and alive to all possibilities when it comes to driving their business forward, especially in a period of increased competition?

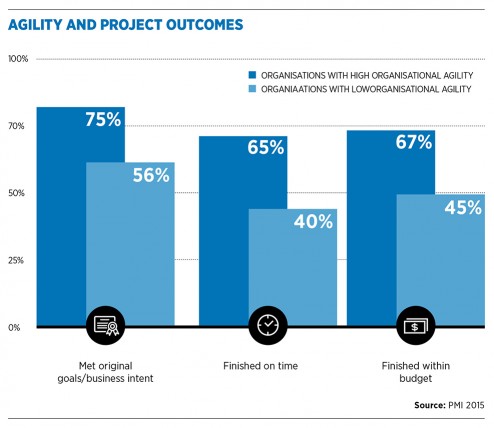

So it is not surprising agile methods are becoming more and more popular as organisations seek to respond faster and more effectively to an increasing pace of change, especially in the way they manage projects that produce new products or improved ways of working.

Originally conceived as a means of better managing software development, agile methods involve breaking a project into a series of steps known as sprints, rapidly testing work and holding daily meetings or scrums to review progress. Close collaboration among team members and with those who have commissioned the work is also an important feature of agile project management.

Agile techniques have a lot in common with well-established lean and six sigma methodologies, which are widely used in manufacturing to hone production processes by eliminating waste and making continuous, small improvements.

Agile methods involve breaking a project into a series of steps known as sprints, rapidly testing work and holding daily meetings or scrums to review progress

Although large high-tech companies such as Google, Microsoft and IBM have adopted agile to develop their products, up until now agile has been regarded as best suited to small, entrepreneurial organisations because of the high degree of co-operation and quick reworking involved in projects that use the methodology.

IBM’s vice president of rational product development and customer support, Harish Grama, is a firm believer that with the right processes, tools and discipline, larger enterprises have a lot to gain from adopting agile. “As you increase team size and distribution, even in different buildings, you need better tools that give you the same notion of putting Post-its on a whiteboard,” he says.

Organisations that have project personnel spread across different locations might have several scrums working together, co-ordinated by a so-called scrum of scrums, consisting of representatives from the other scrums. In this way groups of scrums can work independently, but still be directed centrally.

But it requires careful co-ordination. “On our current project we do cross-team planning every three months face to face. We define a backlog [list of tasks] for three months and iteration-level planning for the next iteration, so that every team knows what they are working on,” explains Sunit Parekh of ThoughtWorks, a developer of agile software tools.

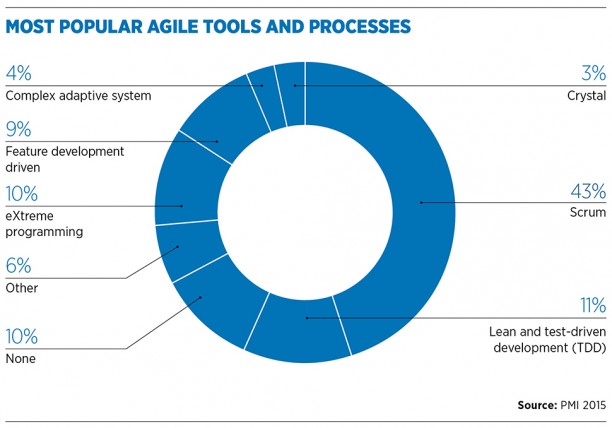

Others are more sceptical. “Scrum is the most popular agile technique, but it doesn’t scale well. And while scrum improves the effectiveness of individual teams, productivity gains fall off sharply on large projects with many teams,” observes John Walker, director of technical marketing at software company Perforce.

Nowhere is the need for more agile thinking greater than in the UK public sector, which not only manages some of the biggest IT projects in the country, but has also overseen some of its costliest failures. Many of these development programmes, such as the NHS Connecting for Health project, which was halted at a cost of £20 billion, were poorly managed and proved too inflexible to adapt to changes in technology and user-needs without incurring huge extra costs.

For some years agile techniques have been touted as an alternative to the more structured waterfall approach used on many problem projects of the past. Projects run along agile lines, proponents in the UK Cabinet Office argue, benefit from being closer to customers, having greater transparency and being more adaptable.

One measure of the government’s determination to spread the message about agile has been the recent launch of a new version of the PRINCE2 (PRojects IN Controlled Environments), the more than 25-year-old standard widely used to manage public-sector projects. PRINCE2 agile framework combines structured project management with agile project development.

The move to agile has had its successes. For example, a Department for Work and Pensions system for administering the Carers Allowance for people looking after the sick and disabled at home scored a 90 per cent approval rating from carers when it was introduced. This high score was achieved by producing an early “beta” version, testing it with users and making revisions based on the feedback that was received.

Increasingly, agile development is seen as an option for much larger public-sector projects – the GOV.UK web portal was built using agile principles – and managers see that the principles can be used much more widely than for development of software.

For example, the Ministry of Justice is using agile methods on a non-digital project that involves organising its estates team across a cluster of government departments. With the help of IT specialists, who are providing agile coaching, the project team is working on an initial “discovery” phase and identifying a small piece of the project to test in a subsequent “alpha” phase.

However, agile has not been an unalloyed success. The importance of applying agile techniques correctly is underlined by a failed project commissioned by Surrey Police. The force contracted software company Memex in 2011 to develop a system called Siren to hold criminal records and details of crimes, but the project was canned two years later at a cost of nearly £15 million.

A subsequent review by consultants Grant Thornton detailed numerous shortcomings, including the fact that although Memex had been appointed because the company was committed to agile development techniques, none were apparently applied to Siren.

“The lack of understanding of the agile approach was evident from our interviews of staff. None of the people we interviewed within the force were able to say which particular variant of agile was used,” Grant Thornton reported.

The consultants detailed a lack of communication between the developer and Surrey Police, muddled plans and a functional specification for the system that was never formally agreed between the force and Memex.

Daniel Thornton of the Institute for Government neatly sums up the situation: “Agility is not a panacea. Any project needs resources and people with experience, authority, and commitment to see it through. Agility does not guarantee these things, but it does help managers to focus on producing things of value to their customers – and when money is short, that’s more important than ever.”