Yi sees the back of her cab as more than just a conveyance; it’s a therapists’ couch, a safe space to unburden. “I want people to get out of my car smiling,” she says, steering the car beneath the tangled limbs of the trees on Singapore’s East Coast Parkway.

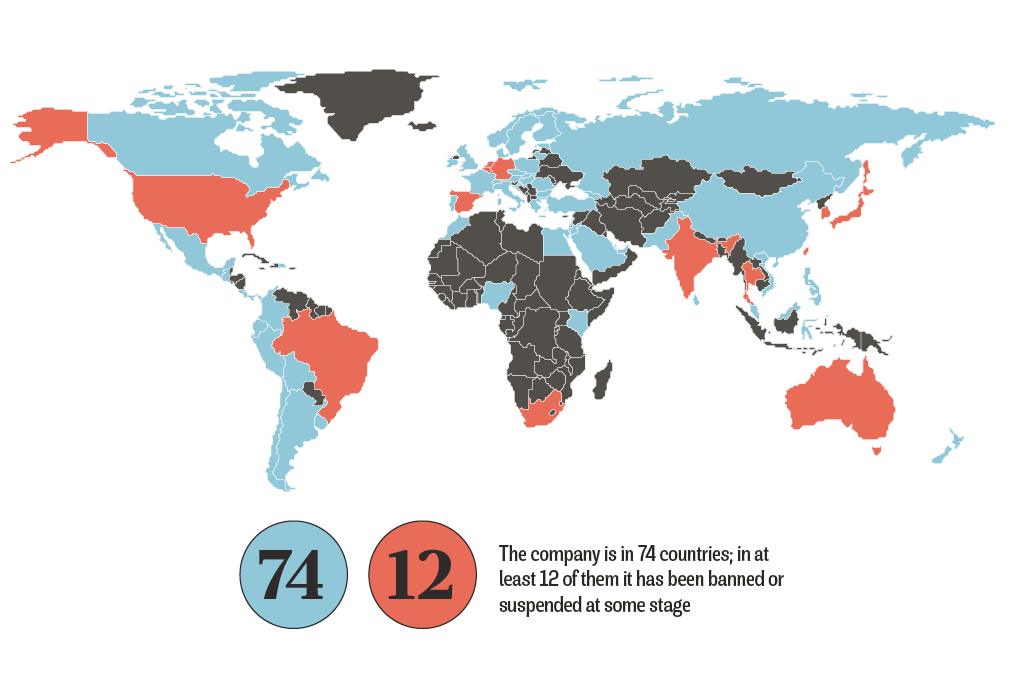

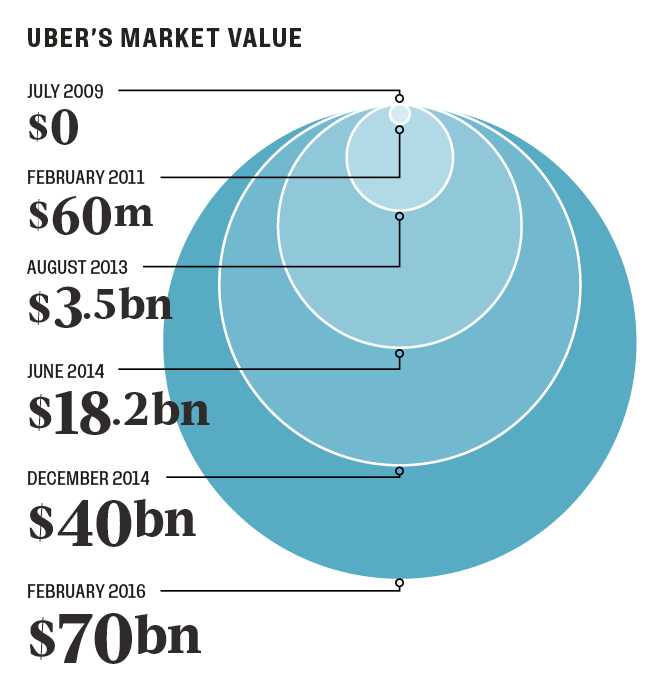

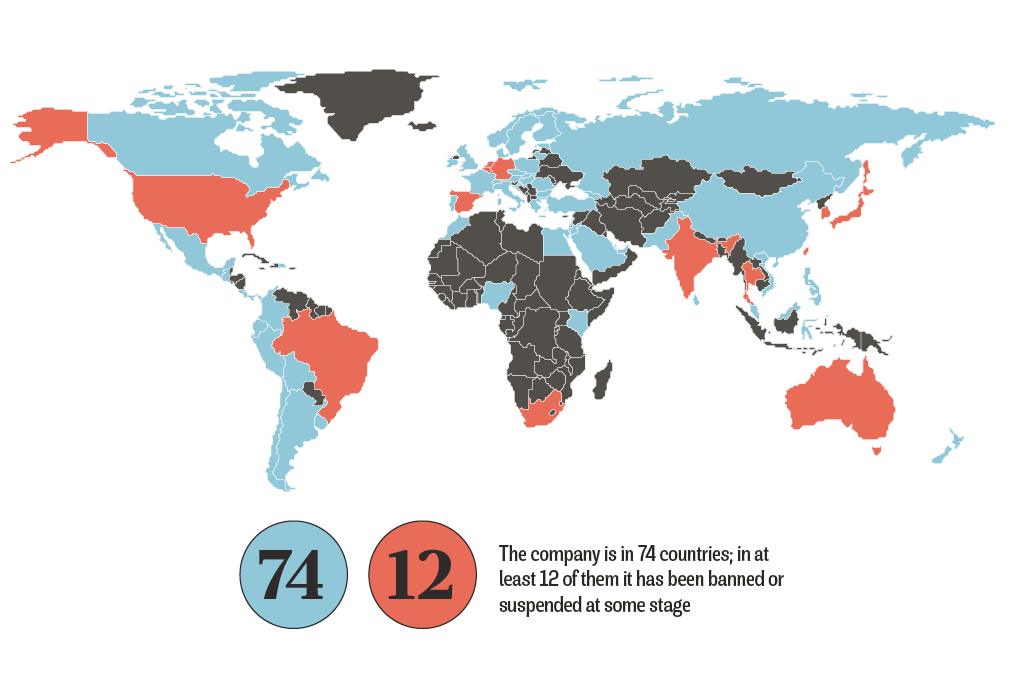

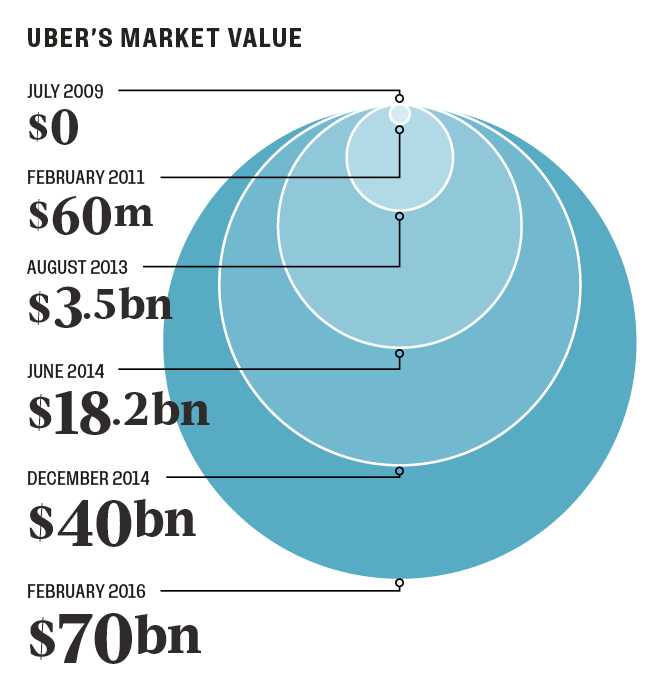

Over the past year, she has seen a few of her fellow drivers leaving the licensed sector to join Uber, the car sharing service that has grown from a venture capital-funded start up to an estimated £50 billion company in under seven years, its impact on customer behaviour marked by its transition from a noun to a verb. Uber launched in its 400th city in late March, adding Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, to its list of destinations.

There were 327,000 Uber drivers in the US as of December 2015, and the number of drivers in the UK is expected to reach more than 42,000 this year

The company’s success has been in allowing drivers and passengers to skirt the formal taxi businesses and ‘share’ space in cars, disintermediating a heavily regulated sector to offer cheaper rides and, in theory, ordinary drivers to make a few dollars on the side.

Source: Crunchbase

In many cases it has essentially become professionalised, with Uber drivers making the bulk of their income on the platform, leading to accusations that, rather than being a ‘sharing’ business, it is instead a mechanism for drivers to avoid onerous safety regulations and training, and for the company to avoid its responsibility for passengers and its ‘partners’ — who provide its service, but are not employees.

Today, from Berlin to Bangkok, it is bumping up against those regulations, and against opposition from militant taxi drivers. On March 22, Indonesia’s capital of Jakarta was brought to a standstill by taxi drivers protesting against Uber and its competitors. In a dozen markets, Uber has faced bans and regulatory action.

“This is still an embryonic, yet exploding market. Regulation does need to catch up, but it does need to be appropriate and proportionate,” says Benita Matofska, founder and ‘chief sharer’ at sharing economy consultancy The People Who Share. In fast-moving, disruptive industries, regulators often lag behind the companies that are paving the way, she says.

Matofska takes issue with Uber’s position as the standard bearer for sharing. Rather than enabling people to use cars more efficiently, the company has actually increased the number of vehicles on the road. “I absolutely take the stance that Uber is not part of the sharing economy,” she says.