News that the UK economy was growing faster than expected ahead of the June 23 Brexit vote has given a slight boost to a government staring down the barrel of a new recession.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics showed that GDP grew 0.6 per cent in the second quarter of 2016, up from 0.4 per cent in the first quarter. The Markit purchasing managers’ index, a widely-used snapshot of business activity, slumped dramatically between June and July, suggesting that the economy is heading for a sharp downturn.

Even the anaemic growth so far this year is unlikely to be fully felt by the population. New research from the Boston Consulting Group shows that the UK is poor at converting economic growth into wellbeing for its population. The company’s Sustainable Economic Development Assessment measures wellbeing across a range of social and economic indicators, from wealth inequality and employment to environmental factors and the strength of civil society. The UK is noticeably worse than many developing countries, and than other Northern European economies.

The UK is noticeably worse than many developing countries, and than other Northern European economies

“Germany is an example of a Western country – a slow growth-type country – that has still been able to turn the growth it does have into improved wellbeing for its population. You compare that to the United Kingdom, which does not do a good job of that,” says Douglas Beal, one of the authors of the report.

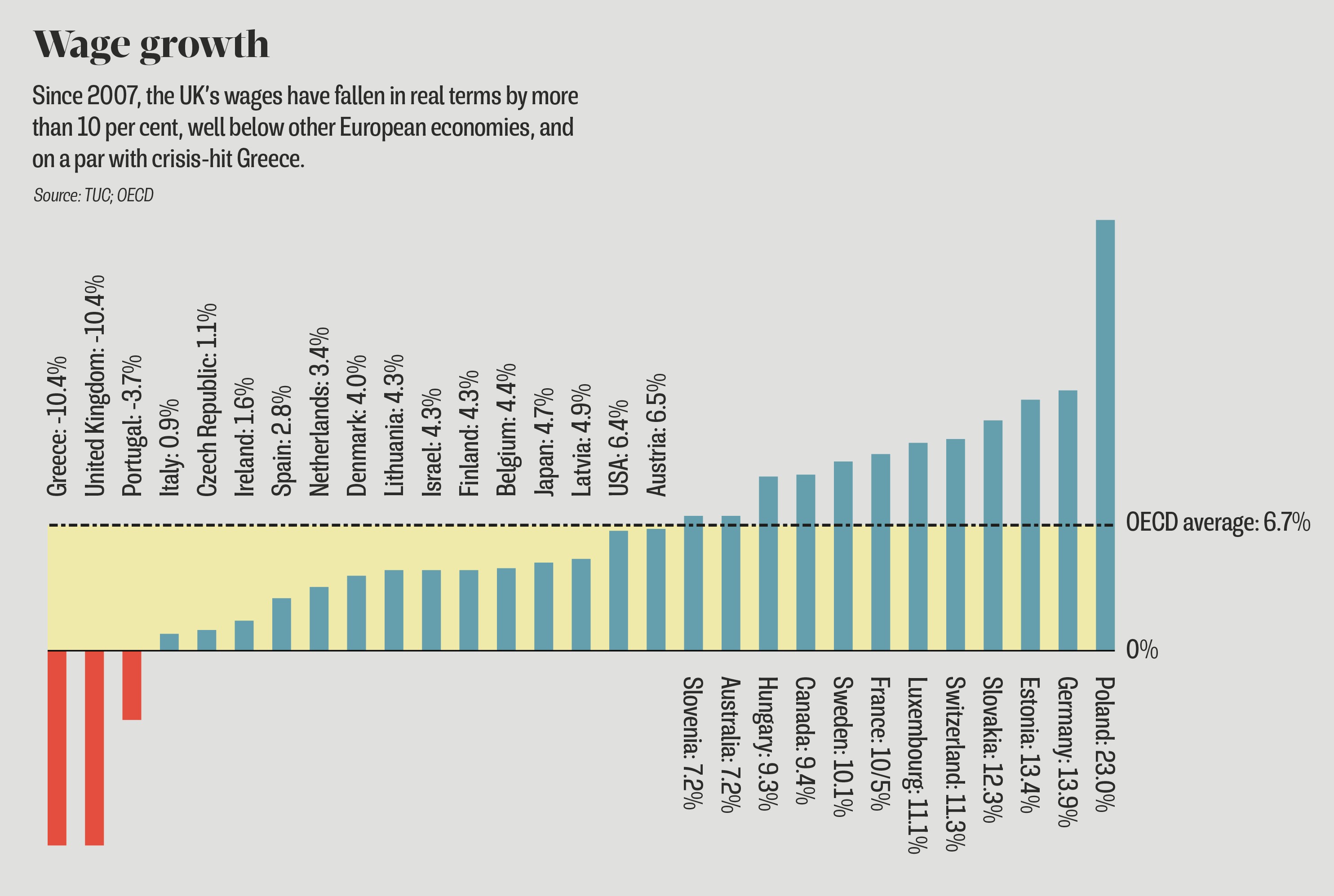

The findings reflect a grim backdrop for working people in the UK. The Trades Union Congress, using data from the OECD, says that between 2007 and 2015, real wages in the UK fell by 10.4 per cent. Within the OECD group of industrialised nations, only Greece – still in the grip of a crippling financial crisis – suffered as badly. On average, wages across the 29 countries rose by 6.7 per cent. In France, wages grew 10.5 per cent in real terms; in Germany, they rose by 13.9 per cent.

The 2016 NatCen British Social Attitudes survey shows that, after converging in the 20th century, a gulf has opened up between older and younger workers – employment rates in the under-40s are now stuck at around 65 per cent; amongst under-25s, the figure is far lower.

Employment on the whole is up, but the social attitudes survey, along with banks of other research reports, show that the shape of that employment has changed. 35 per cent of people surveyed said that they did not have a ‘stable’ job, and 4.5 million people are now self-employed. NatCen notes that: “while employment did not fall proportionately in the years after the 2008 financial crisis, many of the new jobs created… tended to be part-time or self-employed.”

Moving into self-employment, it says, could represent a positive choice – or it could be out of necessity, and in general the self-employed earn less, have fewer in-work benefits and find it harder to access pensions. For those out of work, deep cuts to services have led to falling living standards over the past six years of austerity.

These figures have implications for the economy as a whole, as consumer sectors are a major component of the country’s GDP. Politically, they show that years of chasing growth have not created broad-based prosperity, meaning that the May government may need to drastically rethink its economic models.

As BCG’s Beal says: “It’s important that governments, as they think about policy, as they think about decisions, use a broader measure of inputs.”

News that the UK economy was growing faster than expected ahead of the June 23 Brexit vote has given a slight boost to a government staring down the barrel of a new recession.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics showed that GDP grew 0.6 per cent in the second quarter of 2016, up from 0.4 per cent in the first quarter. The Markit purchasing managers’ index, a widely-used snapshot of business activity, slumped dramatically between June and July, suggesting that the economy is heading for a sharp downturn.

Even the anaemic growth so far this year is unlikely to be fully felt by the population. New research from the Boston Consulting Group shows that the UK is poor at converting economic growth into wellbeing for its population. The company’s Sustainable Economic Development Assessment measures wellbeing across a range of social and economic indicators, from wealth inequality and employment to environmental factors and the strength of civil society. The UK is noticeably worse than many developing countries, and than other Northern European economies.

The UK is noticeably worse than many developing countries, and than other Northern European economies