The first known fatal accident caused by a self-driving car occurred on May 7 when a Tesla Model S in Autopilot mode crashed into a tractor-trailer crossing a Florida highway. Investigations are under way into whether the Tesla Model S’s semi-autonomous system was to blame.

Mobileye, the technology company behind Autopilot, offered some clarification. “This incident involved a laterally crossing vehicle, which current-generation AEB (autonomous emergency braking) systems are not designed to actuate upon,” they said.

This was not the first reported accident caused by a self-driving car. On February 14, a Google autonomous vehicle collided with a bus while merging into traffic. Fortunately, this was a low-speed collision with no casualties.

As a result of the two incidents, Google has refined its software to recognise that buses are less likely to yield to traffic and from 2018 Mobileye systems will include lateral-turn-across-path (LTAP) detection capabilities.

This highlights one of the main advantages of autonomous cars – they collect and transmit data in real time, so the entire fleet can be improved as a result of the data related to any and every incident involving a driverless vehicle. And they can also react to weather and traffic conditions.

Out on the road

The latest BI Intelligence report anticipates that there will be ten million self-driving cars on the road by 2020. The market for driverless cars is expected to top £100 billion by 2021.

Volvo will start testing its driverless cars on public roads around London in 2017

Connected cars with internet access, links to other connected objects and assistive technologies include Tesla’s semi-autonomous Model S. Chief executive Elon Musk anticipates producing a fully driverless car within two years. Google’s cars cover more than 10,000 autonomous miles per week.

Mainstream car manufacturers are working on autonomous capability. In May, Fiat Chrysler confirmed a deal with Google to increase its fleet of self-driving cars. BMW recently teamed up with Intel and Mobileye, which also provides BMW’s collision avoidance systems, to work on the BMW iNEXT, BMW’s first fully autonomous car. And in 2017 Nissan’s popular Qashqai will be equipped to drive autonomously on motorways and dual carriageways.

Last year, PSA Peugeot Citroën’s prototype travelled 360 miles on a motorway from Paris to Bordeaux entirely in autonomous mode. Volvo will start testing its driverless cars on public roads around London in 2017.

The fact that the UK did not ratify the European Union convention on road traffic that requires vehicles to have a driver has enabled the government to fund driverless car trials via its £100-million Intelligent Mobility Fund.

Professor Paul Newman, who leads Oxford University’s Mobile Robotics Group, is co-founder of Oxbotica, which provides the autonomous control system for two of the UK’s government-backed driverless car projects. Its Selenium autonomy system powers eight shuttle vehicles, which are being demonstrated in Greenwich as part of the GATEway project. It will also power 40 LUTZ Pathfinder pods carrying members of the public around urban and pedestrianised areas in Milton Keynes and Coventry.

Who’s liable?

Regulation needs to catch up with technology, particularly around accident liability. The Modern Transport Bill will include changes to domestic road traffic legislation and facilitate new types of motor insurance products.

Peter Allchorne, a partner in DAC Beachcroft’s motor services division, explains that motor insurance will need to encompass traditional liability when the driver is in control and product liability when the vehicle is operating in autonomous mode.

Volvo has confirmed it will accept liability where it can be demonstrated that an accident occurred as a result of a defect in one of its vehicles while operating in driverless mode. “One can envisage evidential disputes as to whether a vehicle was defective and/or operating in autonomous mode at the point of collision,” says Mr Allchorne.

Barriers to adoption include road infrastructure. Autonomous vehicles will need to interact with street furniture and respond to potential hazards. Oxbotica is working with insurer XL Catlin. “We expect there to be fewer accidents,” says Professor Newman. “Autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles share data. So the audit can be between the vehicle, the insurer and all the other vehicles the insurer covers. Insurers will be able to identify what causes accidents and manufacturers will be able to respond.”

Although in theory fewer accidents would reduce claims and premiums, the saving could be offset by higher repair costs due to the complexity of driverless cars. Furthermore, the risk will shift from the driver to the manufacturer. Insurance brokers Adrian Flux recently launched the UK’s first driverless car insurance policy and 13 motor insurers formed the Automated Driving Insurance Group.

Andrew Joint, a partner at Kemp Little, believes the law has to decide whether to give artificial intelligence a legal status because it is replacing the person driving the vehicle and how much responsibility to place on the manufacturer. “It’s about reclassifying what we mean by driver,” he says.

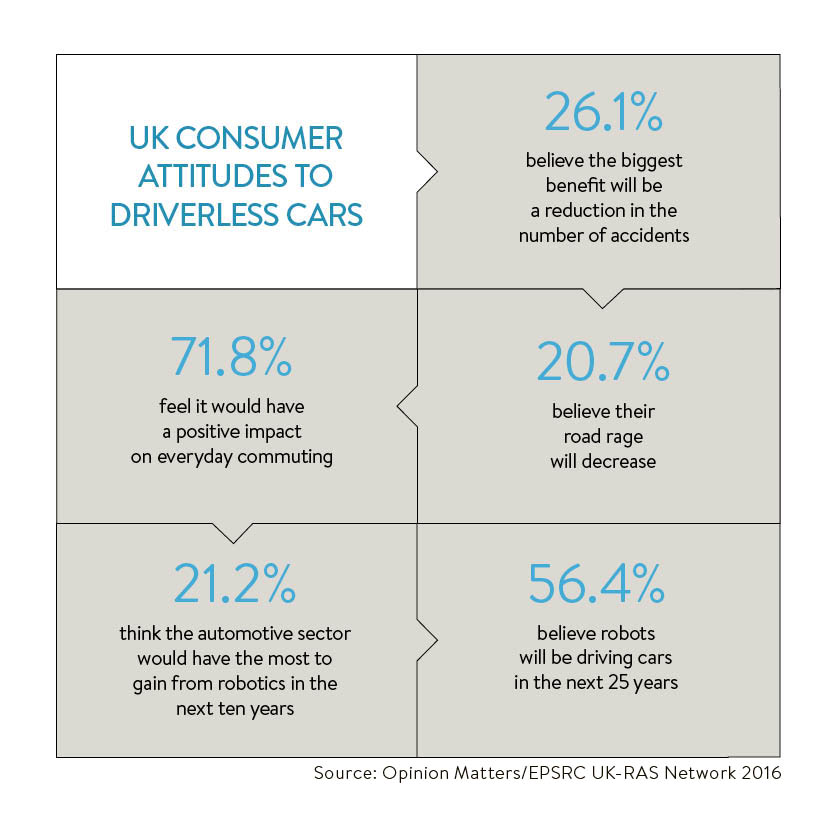

Perhaps reluctance to place their trust in an algorithm explains why people agree that driverless cars are safer, but don’t feel safe in them. A KPMG report for the Society of Motor Manufactures and Traders claims that by 2030 autonomous cars will have saved 2,500 lives by preventing 25,000 serious accidents. However, more than half of 4,000 respondents to a What Car? survey felt unsafe or very unsafe travelling in a fully autonomous vehicle.

Kevin Chesters, chief strategy officer at advertising and marketing agency Ogilvy & Mather, observes that most people have no issues about being a passenger in autonomous transportation such as London’s Docklands Light Railway, being driven by someone else, or relying on satnav or park assist. “The challenge is psychology rather than technology,” he says.

Tom Roberts, managing director at Tribal Worldwide London, believes the confusion will be resolved during the transition to driverless cars. “Rather than building systems that are designed around how humans drive, we need to reimagine the driving experience. Driverless technology isn’t there yet; for example, LIDAR machine vision does not work well in bad weather,” he says.

We may buy into autonomous cars, but will we buy them? A long-term consideration is the potential disruption to automotive manufacturing of combining autonomous transportation with the sharing economy.

Dave Leggett, editor of just-auto, a website that analyses industry trends and emerging technologies, concludes: “Car manufacturers would like customers to carry on buying cars on three-year cycles and taking out finance. However, car sharing firms like Zipcar and ride-share operations like Uber are already disrupting the market.”

Out on the road

Who's liable?