Squeezing a house through a nozzle, like a pâtissier pumping fondant cream from a piping bag, may not be everyone’s idea of cutting-edge construction. But in Dubai, it’s all part of the plan.

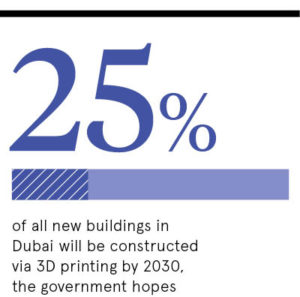

The glitzy emirate aspires to have a quarter of all new buildings constructed via 3D printing by 2030. Emaar, one of the Arabian Gulf’s leading property developers, is heralding its nascent Arabian Ranches III residential project as offering Dubai’s first such dwelling.

Profit margins in construction are smaller, meaning it is harder to introduce radical change

3D printing, or additive manufacturing, itself is not a new technology, harking back to the 1980s. Fabricating a three-dimensional model, or prototype, from a computer-aided design by adding successive layers of material is now standard practice in many industries, ranging from aerospace and architecture to medicine and high-end manufacturing.

McKinsey, the consultancy, estimates the technique could have an annual economic impact worth $550 billion by 2025.

How does 3D printing in construction work?

Construction, however, is proving a tougher challenge. It is thought that 20 commercial buildings around the world have been built using 3D printing so far, the first being by COBOD International, in the Danish capital Copenhagen, in 2017.

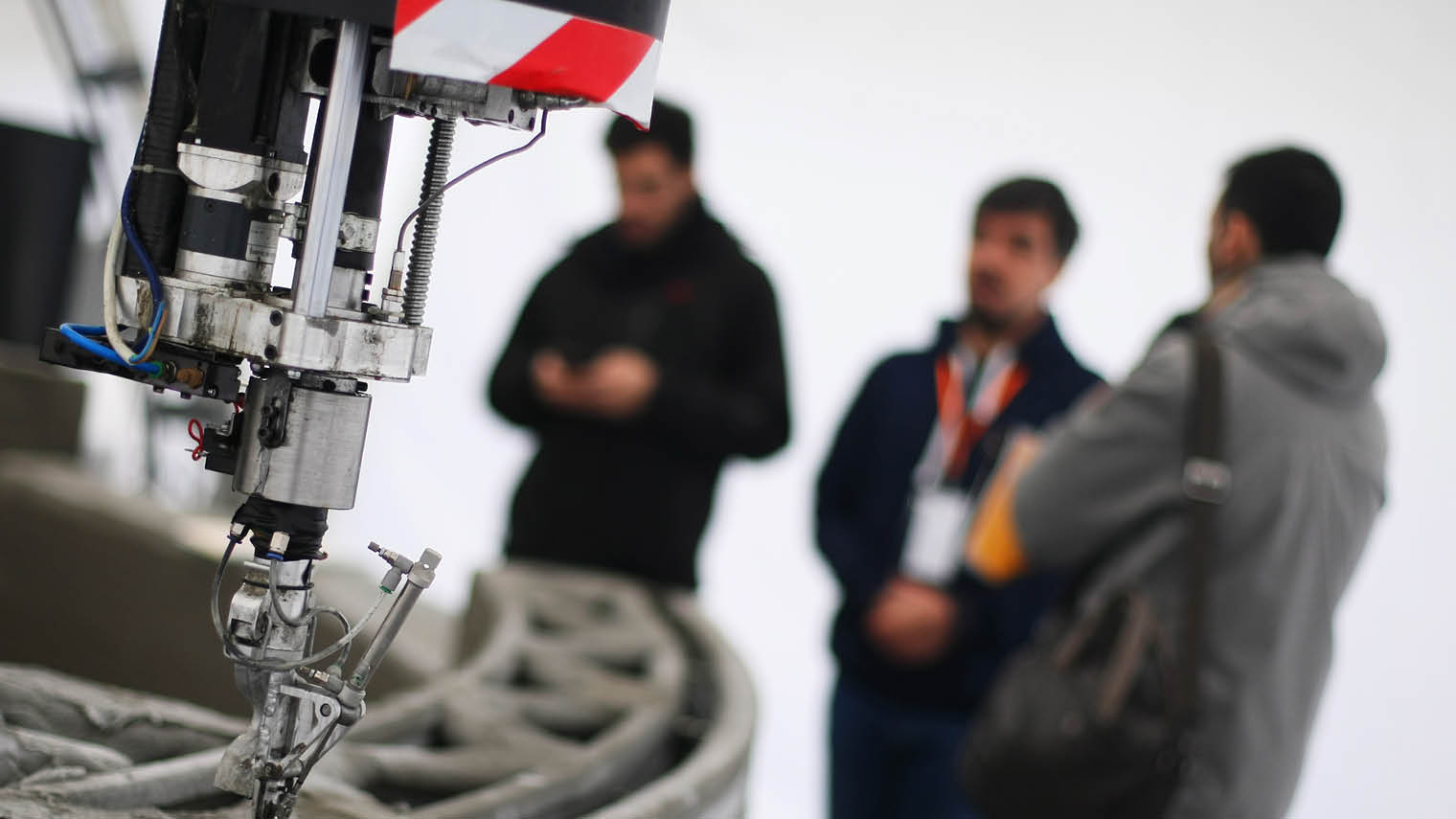

In practice, concrete is squeezed out of a nozzle attached to a computer-programmed robotic arm, either stationary or travelling along rails, in successive strips, layer upon layer, to produce the desired building structure, such as an exterior or interior wall, or component, like an archway or void.

As with many other superlatives, such as the world’s tallest skyscraper and “smartest” smart city, Dubai is adamant in its ambition to be crowned leader of high-tech construction. It already boasts the world’s first 3D-printed office and a 3D-printed drone research laboratory. The 3D-printed office is reported to have cost only $140,000 to build.

As with many other superlatives, such as the world’s tallest skyscraper and “smartest” smart city, Dubai is adamant in its ambition to be crowned leader of high-tech construction. It already boasts the world’s first 3D-printed office and a 3D-printed drone research laboratory. The 3D-printed office is reported to have cost only $140,000 to build.

Advocates claim the technique offers construction that is faster, cheaper and more environmentally friendly than traditional building methods. They point to accelerated delivery of homes, greater flexibility in design, reduced cost of construction, more efficient use of materials and higher levels of sustainability by reducing waste typical of construction, and even less noise pollution.

Specifically, industry experts identify seamless production of objects from a numerical design and access to a wide range of geometries for the final object, most impossible or very expensive to realise with traditional processing techniques, as being the prime advantages of 3D printing.

Could printing buildings save money and time?

Plus, the commercial appeal to big builders seems irresistible. According to SmarTech Publishing, a market forecaster, by 2027 the 3D-printed construction industry will be worth $40 billion.

Henrik Lund-Nielsen, chief executive of COBOD International, works with customers in Dubai. He claims the potential cost-savings in Europe or the United States, where building-site labour is more expensive, could run into billions. According to Mr Lund-Nielsen, the Dubai government’s drive will help boost 3D printing’s appeal to the construction industry as it reveals major cost-savings.

But some take a less breezy view of 3D printing’s attraction to the worldwide construction industry. Sergio Cavalaro, reader in infrastructure systems at the School of Architecture, Building and Civil Engineering, Loughborough University, is currently engaged in proprietary research into 3D printing’s application in the global construction sector.

He says the very structure of the sector itself mitigates against widespread adoption. “Inertia is higher in the construction sector than in other industries, such as automotive. It is not so vertically organised. Profit margins are also smaller, meaning it is harder to introduce radical change,” he says.

Dr Cavalaro also believes the novelty factor in owning a 3D-printed home may soon wear off. He points out: “Customers paying a premium for a 3D-printed home might not realise a profitable resale value once the technology has become commonplace.”

Having said that, Dr Cavalaro is a convert to the promise of the technology, albeit adding a caveat to its cost. “3D printing is excellent for complex shape elements, such as voids. Its advantage is that it can be used to reduce material consumption and deliver optimum components. But given the technology, it’s likely to be more expensive than the traditional method of construction,” he says.

The challenges of concrete 3D printing

Given that concrete is the prime construction material extruded in building 3D-printed structures, LafargeHolcim, one of the world’s largest concrete manufacturers and suppliers to the global construction industry, has a keen eye on the developing market.

Edelio Bermejo, head of research and development at the Switzerland-headquartered firm, describes the application of 3D printing to the industry as “emerging”, but with “huge potential”. He says: “3D printing will, in fact, open the market for more cement-based materials in construction systems and this is in line with our strategy of growing our value-added business.”

In 2016, LafargeHolcim entered into a partnership with French 3D-printing systems provider XtreeE to explore ways of collaborating on the technology.

Mr Bermejo stresses the technical challenges in deploying 3D-printing technology for residential and commercial building purposes are manifold. “The main challenges for concrete 3D printing are related to reinforcement, further understanding of material processing and properties, for example durability, and robustness of the process. The construction industry will also need to understand how to best design structures with this new technology and all will have to be reflected in design codes,” he says.

What could the impact be on construction jobs?

Construction is, typically, a very labour-intensive industry; just observe any major building site. Understandably, building workers will be wary of technology that ultimately obviates the need for skilled or semi-skilled staff. Should employees or contractors fear the impact the adoption of 3D printing across the construction industry will have on their jobs and employment prospects?

LafargeHoclim’s Mr Bermejo is sanguine, pointing to 3D printing being just one element in the overall industrialisation and digitisation of the construction industry. “As was the case in other industries, this will lead to a shift to higher-skilled workers and newly emerging job profiles along the construction value chain,” he says.

“Education and training are key for workers to adapt to this change, and digitisation can also help in this aspect. We also envisage the potential for 3D printing and digitisation to improve site safety for construction workers.”

Overall, though, concrete 3D printing is still in its infancy. But ambitious targets, like those set in Dubai, will certainly help boost the development of the technology and bring it closer to the mass construction market.