When two hacking experts demonstrated to a WIRED journalist how they could access the computer system of the Jeep Cherokee he was driving, it highlighted a worrying threat in an increasingly connected world. Through malicious code, the hackers were able to control everything from the air conditioning and music to the vehicle’s steering, brakes and transmission.

As the internet of things (IoT) takes off it will inevitably introduce new cyber vulnerabilities, says Michael Carr, technology practice leader at Argo Group. “The biggest concern with IoT is you have masses of multiplication of the attack surface. Every connected device is a point of entry into a network,” he warns.

Technology research firm Gartner forecasts that 20.8 billion connected things will be in use worldwide by 2020, up from 6.4 billion today. It also anticipates that up to 20 per cent of annual security budgets will go towards addressing compromises in IoT security.

The difficulty for security experts, corporates, IT departments and insurers is that many IoT devices are not designed with security in mind. “Up until recent times connected devices tended to be things that we took some effort to defend – desktop and laptop computers, even mobile phones and certainly servers,” says Mr Carr. “When you start connecting thermostats and refrigerators there’s a real question if those things are going to be engineered securely or if they could become the weak link.”

Data breach

The data breach at Target in 2014 offers an example of how such weak links can be exploited. The personal data of more than 100 million individuals was compromised after hackers used stolen credentials from a contractor to access the retailer’s corporate system. “They had the vulnerability not in their own system, but in the system of their heating and ventilation supply company,” explains Graeme King, senior cyber underwriter at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty (AGCS). “By exploiting that vulnerability they got in.”

As the Jeep hacking stunt demonstrated, another emerging threat emanating from a connected world is actual physical harm arising from an intrusion. Potential scenarios range from individual attacks, such as tampering with the thermostat at a food or pharmaceutical warehouse and causing spoilage of perishable goods, through to major incidents, such as taking down a power grid.

In 2014, a blast furnace at a German steel mill suffered massive damage after cyber attackers breached the mill’s control system. This, along with politically motivated attacks such as the Ukraine power grid attack of December 2015 and 2010 stuxnet attack on Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant in Iran, demonstrate these scenarios are not just the stuff of Hollywood blockbusters.

They also indicate the potential for systemic risk in a world where everything is connected. “Most cyber attacks carried out by criminals are about extracting extortion payments or stealing data to sell on,” says Mr Carr. “Criminals are typically not going to be perpetrating something that could turn into a systemic attack. However, politically motivated attackers might be much more interested in causing systemic damage because their motivation isn’t monetary, except maybe to wreck the economy of the country or region they were attacking.”

Last December’s cyber attack on Ukraine’s power grid and subsequent blackout demonstrate the emerging threat emanating from a connected world

Supervisory control and data acquisition systems used by industrial and utility companies are typically not connected to the internet, a practice known as “air gapping”. But this defence could be obsolete in the future. “One of the hot uses of IoT is sensors that allow you to manage power usage more optimally,” says Mr Carr. “That means you have sensors on the power meters of homes and businesses talking to the power generation stations.”

However, the ongoing concern for the vast majority of businesses will continue to be data protection and business continuity, says Joshua Goldfarb, vice president and chief technology officer of emerging technologies at cyber security and malware protection firm FireEye. “One of the biggest risks organisations face these days is the theft of sensitive confidential and proprietary information,” he says. “Theft of data can cause brand damage, loss of revenue, lawsuits and fines for violating privacy laws.

[embed_related]

“It is a risk that can be mitigated in various ways. But what people sometimes forget is that attackers are continuously evolving. Lately they’ve been doing quite a lot of attacks to compromise user credentials, allowing them to masquerade as a legitimate user.”

Making millions

Making millions

Cyber crime is set to be worth $2.1 trillion by 2019, according to Juniper Research. In addition to data theft, 2016 has seen the proliferation of cyber extortion. The cryptolocker gang is understood to have made more than $30 million in 2015 using relatively simple ransomware.

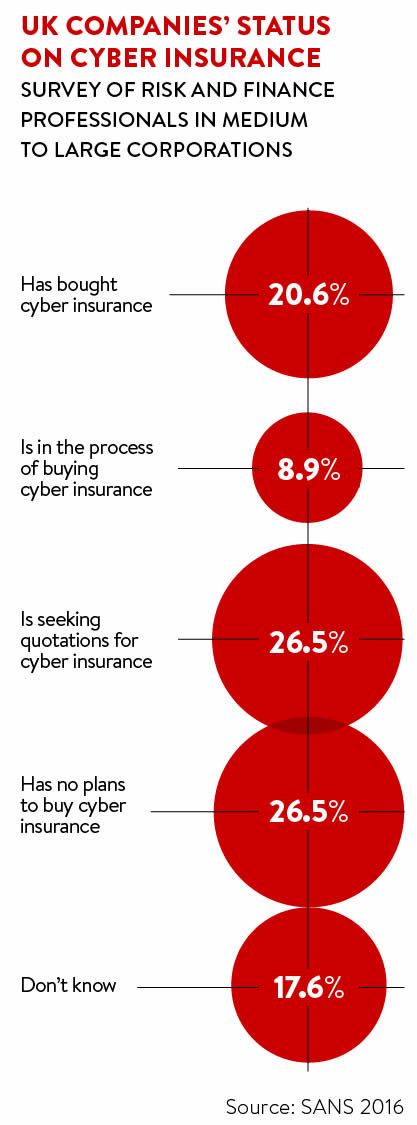

“The insurance industry in the UK is ready for this, but the clients are not yet buying the product in their droves. Had there been widespread uptake of insurance to date we would have had a much bigger handle on the scale of this problem. An insurance policy would probably help an awful lot of these companies, enabling them to identify where that threat is coming from, plug the gap, restore the data and secure their systems from more of the same,” says Mr King at AGCS.

Cyber insurance providers will continuously need to adapt their products and services to the changing threat environment

The impending European Commission’s General Data Protection Regulation and headline-hitting data breach exposés will continue to drive greater demand for cyber cover. Mr King says: “That’s when you’ll see the real upswing, as media headlines start causing people embarrassment.”

Cyber insurance providers will continuously need to adapt their products and services to the changing threat environment. If one of the objectives of future cyber attackers is to cause property damage, bodily harm, pollution or widespread power outages, it could mean insurance claims are made under more traditional classes of business, including commercial and residential property, motor, environmental, business interruption, general and professional liability, and accident and health.

While some cyber products offer cover for physical damage, this is not yet widespread and currently cyber exposures are not being priced into other insurance policies. “You either need to start adding cyber to all classes or introducing cyber exclusions and expanding cyber policies to encompass physical damage and bodily injury,” says Argo Group’s Mr Carr.

Insurance buyers may well prefer the former. The latter is preferable from an insurer’s perspective, as with the first scenario there is a possibility that a single piece of malware could end up triggering coverage for six different contracts for the same insured. “Whereas if all the cyber stuff was in the cyber policy, I’d at least be prepared to manage my total exposure – I don’t think the industry has figured this out yet,” Mr Carr concludes.

Data breach