As the bright lights fade on the sporting carnival that was Rio 2016, you wonder what the founder of the Games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, would have made of it. The host nation of the 31st Olympiad does not exactly embody the spirit of fair play, enshrined in de Coubertin’s Olympic Charter.

The Games shone the world’s spotlight on a country in the midst of its biggest corruption scandal, economic recession and a political crisis that has seen its president impeached and more than half its congress under investigation.

At the centre of the storm that has rocked Brazil is the widespread corruption uncovered during Operação Lava Jato or Operation Car Wash. It is alleged that executives at state-controlled oil company Petrobas accepted bribes in return for awarding construction contracts at inflated prices, and channelled funds into the accounts of Petrobas executives and politicians, which funded the electoral campaigns of senior Brazilian politicians.

Huge loss to the state

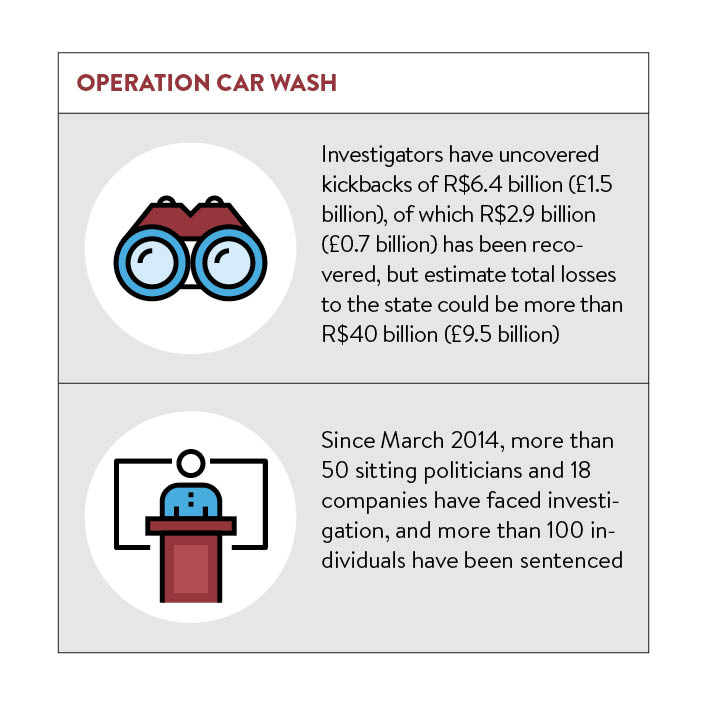

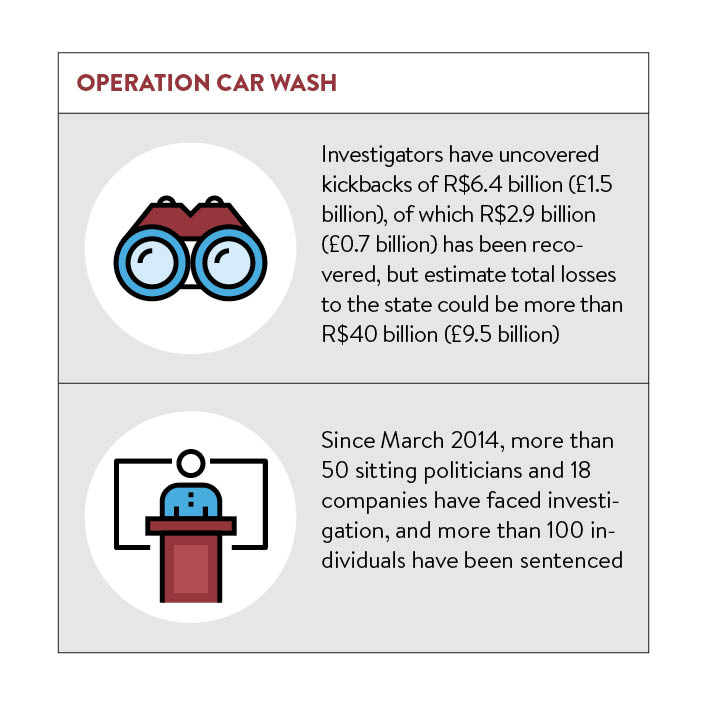

Investigators have uncovered kickbacks of R$6.4 billion (£1.5 billion), of which R$2.9 billion (£692 million) has been recovered, but estimate total losses to the state could be more than R$40 billion (£9.5 billion).

Since March 2014, more than 50 sitting politicians and 18 companies have faced investigation, and more than 100 individuals have been sentenced, including the former treasurer of Brazil’s governing Workers’ Party, João Vaccari Neto, and Renato Duque, Petrobras’s former head of corporate services.

The speaker of Brazil’s lower house of congress, Eduardo Cunha, and the former president Fernando Collor de Mello, who was impeached in 1992, have also been accused of corruption.

To top it off, Dilma Rousseff was impeached as president in August and removed from office following claims of budgetary manipulation.

Set up to tackle the high-level corruption, Brazil’s Ministry for Transparency, Monitoring and Control was itself tainted by the brush of corruption and the minister for transparency forced to resign.

Brazil took the biggest tumble in Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index. Ranked in 76th place in the list of 168 countries, its score, on the scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (squeaky clean), fell from 43 points in 2014 to 38 in 2015.

While all this may look bad to the observer, Isabel Carvalho, partner in the São Paulo office of international law firm Hogan Lovells, insists that what is happening in Brazil is a good thing and demonstrates a clean-up taking place.

The B in the BRIC list of developing countries, Brazil has the eighth biggest economy in the world. It is not unique in the region for tolerating corrupt practices, but its problem is deep rooted.

One reason for the prevalence of corruption, says Naina Patel, a barrister at London’s Blackstone Chambers, is the high level of bureaucracy and regulatory hurdles for doing business, resulting from the large state apparatus that has sought to be an engine of the country’s growth and development.

At the heart of this corrupt culture is the immunity of lawmakers and ministers for most acts of corruption

Alberto Luzarraga, partner and co-head of the Latin America practice at international law firm Linklaters, adds: “Historically, the governing bodies of Brazil have had an overly large influence on the economy, particularly on the exploitation of natural resources and the awarding of corresponding development rights.”

The country has moved from dictatorship and military rule to democracy within the last century, but has not developed the institutions to control corruption, says Mr Luzarraga.

Also at the heart of this corrupt culture, observes James Ramsden QC, barrister at 39 Essex Chambers, is the immunity of lawmakers and ministers for most acts of corruption.

This immunity, explains Peter Van Veen, director of the business integrity programme at Transparency International, means there is little motivation for senators and others to give up political roles. If they do, they risk coming under the spotlight of prosecutors. “Politics has become a bit of a refuge for the corrupt,” he says.

Protests

Lack of enforcement has also been a factor, adds Mr Luzarraga, though this is slowly changing. The trigger for Brazil’s clampdown came in the run-up to its hosting of the 2014 World Cup. Hundreds of thousands of citizens took to the streets in protest over the cost of preparing for the football tournament, as the cost of living rose.

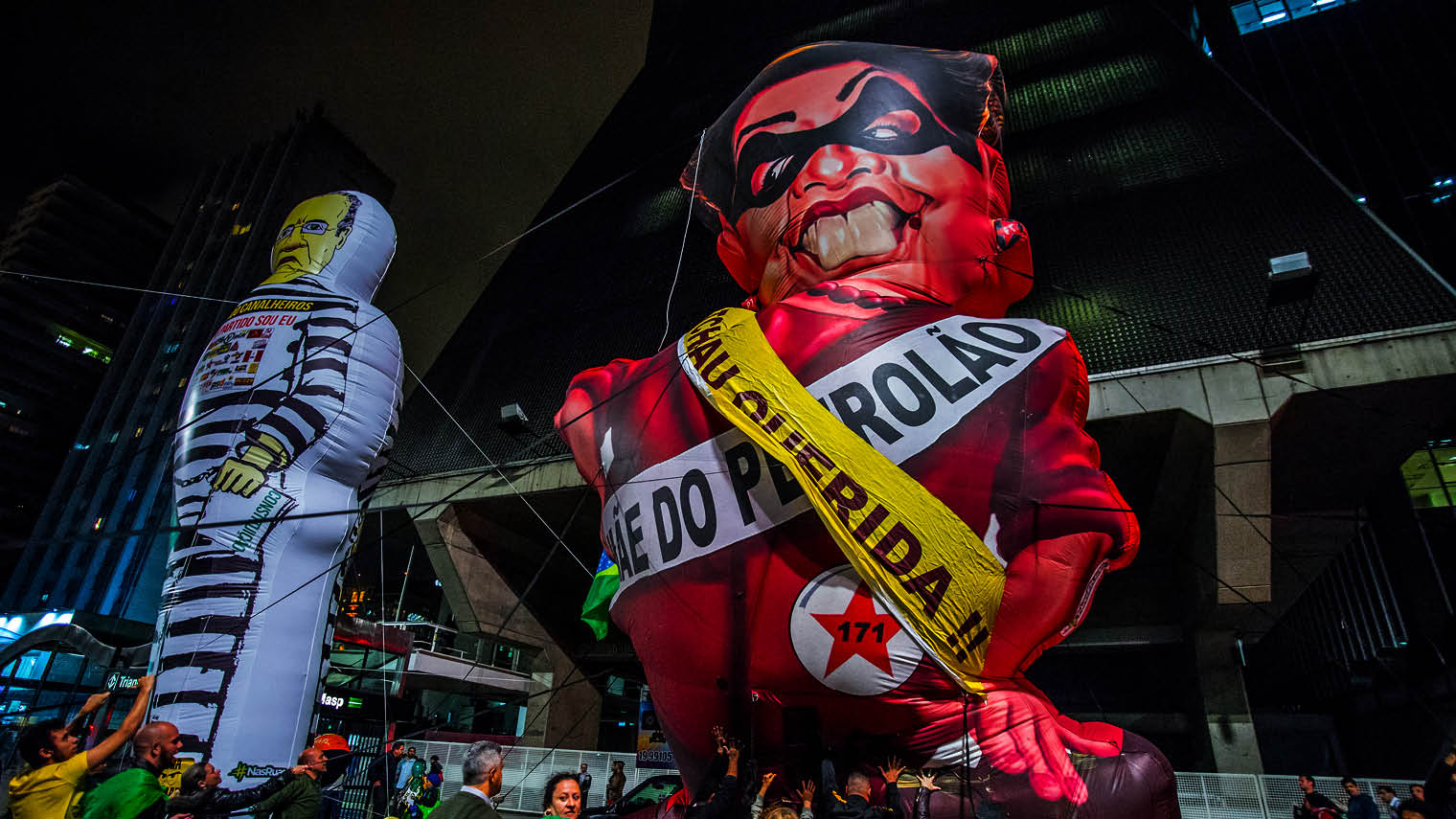

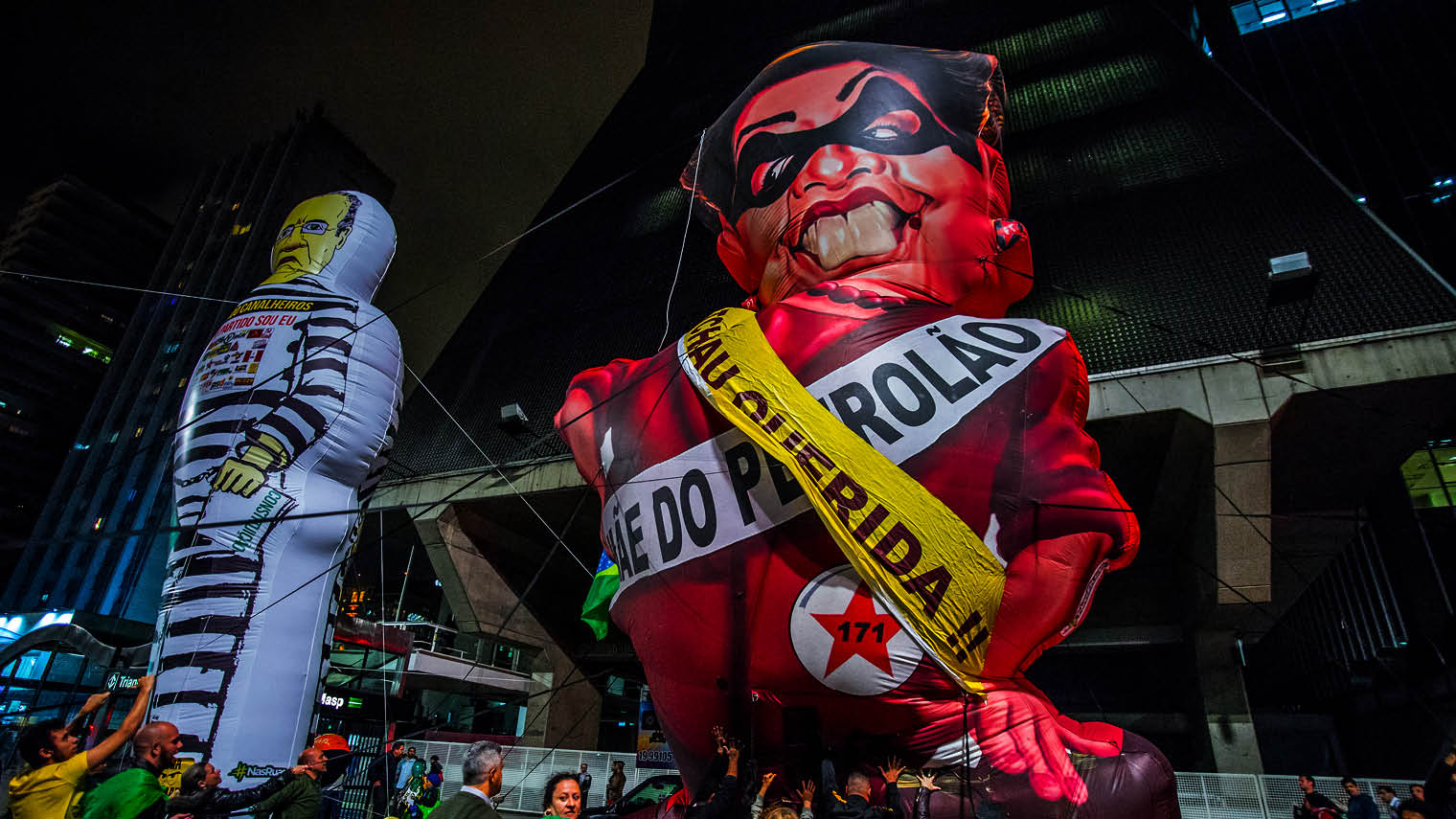

Giant balloons depicting Dilma Roussef and former president Inacio Lula Da Silva during protests in Sao Paulo in April

The protests turned into a call for a wider clean-up and led to the passing of the anti-corruption law that holds companies responsible for the corrupt practices of employees and introduced leniency agreements, which have been used to great effect during Operation Car Wash.

Ms Carvalho observes: “The anti-corruption law was the only good thing to have come out of the World Cup. Losing 7-1 to Germany was a disaster.” The new enforcement regime in Brazil, she says, is changing how people are looking at doing business there. “Due diligence has become much more stringent, and corruption has become a big topic in every mergers and acquisitions transaction.”

With the scale of the Car Wash investigation and the efforts of intrepid prosecutors, who are bringing US prosecutor-type standards and tactics to the country, Brazil “is a test case of what it takes to bring a country out of a cycle of corruption”, says Lance Croffoot-Suede, a partner in international governance and development practices at Linklaters.

While there have been no allegations of corruption in relation to the bidding process for Rio 2016, construction firms that have built some of the venues have come under the glare of the Car Wash inquiry. And, adds Mr Van Veen, alleged kickbacks tainted every construction deal during the 2014 World Cup.

Corruption and sport

The organisation of large sports events, as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) report, Preventing Corruption and Promoting Responsible Business Conduct when Organising Sporting Events, points out, carries high risks of corruption because of the complex financial arrangements required, often under tight schedules.

The Olympics is not alone in courting sporting scandal. FIFA, the world governing body of football, remains mired in the fallout of allegations of wrongdoing in the bidding process for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups, and the International Association of Athletics Federations has been rocked by revelations of corruption by its officials to cover-up widespread doping.

There is general agreement that all the sporting bodies implicated need to clean up their acts, both in relation to their governance, transparency and accountability, and in the way they organise global events.

Though efforts are being taken to address some of the most egregious wrongdoing, Nick De Marco, a sports barrister at Blackstone Chambers, says that until steps are taken to establish independent scrutiny and review, the various reforms of sporting bodies “will be only trifling and scandals will repeat themselves”.

More positively, he adds: “Increased pressure from the public, sports fans, politicians and law enforcement agencies means such radical change in the administration of sport is now firmly on the agenda.”

James Ramsden QC, a barrister at 39 Essex Chambers, agrees the outlook will remain bleak until an overarching sports regulator is in place.

“This could form an extension to the existing Court of Arbitration for Sport, but have powers of investigation and oversight in relation to each sport’s governing body that currently submits to the court’s jurisdiction,” he suggests.

Crispin Rapinet, Hogan Lovells’ global head of investigations into white-collar fraud, calls for the development of an international model of best practice and industry guidelines on adequate procedures.

Indeed, the OECD has already produced the Good Practice Guidance on Internal Controls, Ethics and Compliance, which it says provides a set of measures that are fully relevant to sports organisations and can stamp out corruption.

KICKING OUT CORRUPTION IN WORLD FOOTBALL

A bigger deal than even the Olympics, football’s World Cup is the most lucrative sporting event in the world. According to FIFA, the 2014 Brazil World Cup generated £3.1 billion through broadcasting rights, marketing, ticket sales, hospitality and licensing rights, and raked in £2 billion profit for FIFA.

FIFA Head Quarters

The corruption scandal that has engulfed world football’s governing body has revealed the ugly side of the beautiful game. Following investigations into allegations of corruption surrounding the bidding process that controversially awarded the 2018 and 2022 World Cups to Russia and Qatar respectively, 30 FIFA officials and associates were charged over involvement in accepting millions in bribes and kickbacks over more than 20 years.

What happened, says Alex Kelham, managing associate in the sports business group at law firm Lewis Silkin, was the result of the huge amount of money involved in the commercialisation of the sport. “It became a victim of its own success and provided an opportunity for unscrupulous people to exploit and slice off money on the side,” she says.

And it was allowed to happen, because those who administer the multi-billion-pound sport and hand out the lucrative contracts, says Nick De Marco, a sports barrister at Blackstone Chambers, also regulate the sport.

Darren Roiser, partner in investigations, fraud and compliance at King & Wood Mallesons, adds that FIFA’s status as an unincorporated association under Swiss law means it is not subject to the same corporate governance requirements as, for example, UK limited companies.

The beleaguered organisation is making efforts to clean up, reforming its corporate governance rules and introducing a new four-phase bidding process for the 2026 competition.

What is required, says Crispin Rapinet, global head of investigations into white-collar fraud, at international law firm Hogan Lovells, is a complete culture change and enforcement regime, coupled with greater transparency and accountability, and independent scrutiny of the organisation’s operation.

Huge loss to the state

Protests