From space probes to prosthetics, jewellery to jet engines and concrete to kidneys, the question must be asked: is there nothing that cannot be 3D printed?

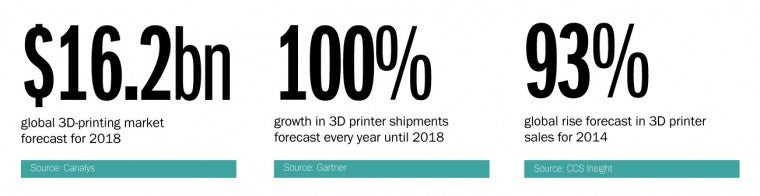

The global market is large and growing, forecast to reach $16.2 billion by 2018. In the UK, government support is standing up to be counted, with £14.7 million announced for a new 3D-printing hub in Coventry.

However, despite the fact it is now more than 30 years since Chuck Hull invented rapid prototyping in 1983, for many, a whiff of alchemy still clings to the world of 3D printing.

Predictions for uptake among the general public remain the stuff of guesstimates. The same poll that found one in ten British adults were prepared to buy into the concept to the tune of £500 each for a 3D printer also discovered four out of ten admitting they had no idea what to do with one.

Business uptake, on the other hand, is on a clear and dramatic upwards trajectory, according to Terry Wohlers, president of Wohlers Associates, publishers of the annual Wohlers Report. “Interest and excitement surrounding additive manufacturing and 3D printing are at an all-time high,” he says. “Corporations, government agencies, researchers and others are investing in the technology in ways not seen in the past. Many are trying to understand where it is headed and how they fit in.

“Some of the biggest companies and brands in the world, such as Adobe, Airbus, Amazon, Autodesk, Boeing, GE, Google, Lockheed Martin and UPS, have made some level of commitment.”

COMMERCIAL ACCEPTANCE

A barometer of UK commercial acceptance, the technologically conservative construction industry is now engaged. An agreement announced between architects Foster + Partners, contractor Skanska, plus Buchan Concrete and Lafarge Tarmac, allows use under licence of pioneering 3D-printing technology developed at Loughborough University.

Simon Austin, professor of structural engineering at the School of Civil and Building Engineering, outlines the breakthrough potential in real applications. “It opens up possibilities of great variation in geometry and performance of concrete building components,” he says. “This is because the price of each one is roughly the same, unlike moulded parts where it is proportional to the number cast from a single, expensive mould. Geometry is ‘free’.”

Rather than looking to 3D print whole buildings or houses, as trialled on a 24-hour turnaround basis in China, the consortium is focused on components such as novel, complex façade panels for high-end projects. Professor Austin is positive but measured in his assessment of roll-out potential. “By 2020, we should see examples of 3D printing applied in a variety of projects around the world, but it will still be niche,” he says.

Some of the biggest companies and brands in the world have made some level of commitment

On commercialisation, his cautious optimism is echoed by Martin Clarke, director of the World Concrete Forum, who says: “The new consortium will open eyes to possibilities. Questions need to be answered, but the prize is very high and credible solutions will be found. I am not convinced, though, that 3D portable machines will be on building sites rather than in permanent precast production facilities.”

CONSUMER PERCEPTIONS

At the other end of the scale, pursuing localised and personalised distributed manufacturing, sits one-of-a-kind 3D-printing platform Kwambio.

Previewed at 3D Printshow London, the platform will allow consumers to customise and personalise designer models, without file transfer, for up to 200 different products, from practical household items and pieces of jewellery, to art and decor. With a few custom clicks, users can bring a design to life in their own home, 3D printing results on the kitchen table.

With more than 1,500 subscribers, 42 per cent in the United States, already signed up to free beta-test the service and future user-fees estimated at between $2 and $15 an item, chief executive and a founder of Kwambio, Volodymyr Usov, attributes its popularity to a combination of customisation, convenience and security.

“No two people are the same and so it should be with your products,” he says. “The main benefit is customisation. Then, as we focus on owners of 3D printers, the second benefit is convenience. Thirdly, while you can have a ‘factory’ at home, you need design skills to make something printable. Those who design 3D models are not willing to post their files on the web, because of piracy. That’s why we consider security the third benefit.”

Also in the personalised production market, though centralised, is Makie Dolls of London, which 3D prints via selective laser sintering (SLS), melting a “dust” of high-quality nylon into the desired shape, layer by layer.

The dolls are finished manually and, interestingly, the marketing points to a consumer perception-gap tension between DIY artisan chic and industrialised automation, describing them as being assembled “by hand with love”.

In development terms, we are perhaps in the “teenage years” of 3D printing. Markets are yet to be made (literally) and there is a sense in which the industry is walking the talk of the consumer.

COMMERCIAL ACCEPTANCE