When Josh Krichefski became chief executive of MediaCom, Britain’s biggest advertising-buying agency, earlier this year, he introduced a rule that banned internal e-mails after 7pm and at weekends to improve his team’s work-life balance.

Rick Hirst, UK chief executive of Carat, says his agency has launched an initiative called Phone Hotel where employees are encouraged to deposit their work phones before going on holiday to ensure they switch off from work.

And Barney Ely, a director at Hays Human Resources, a division of the FTSE 250 recruitment firm, reports that some companies will now shut down their e-mail servers out of hours or automatically delete e-mails when staff are on holiday.

These are just three examples of how businesses are trying to help employees cope with the demands of the “always-on” workplace.

Challenges

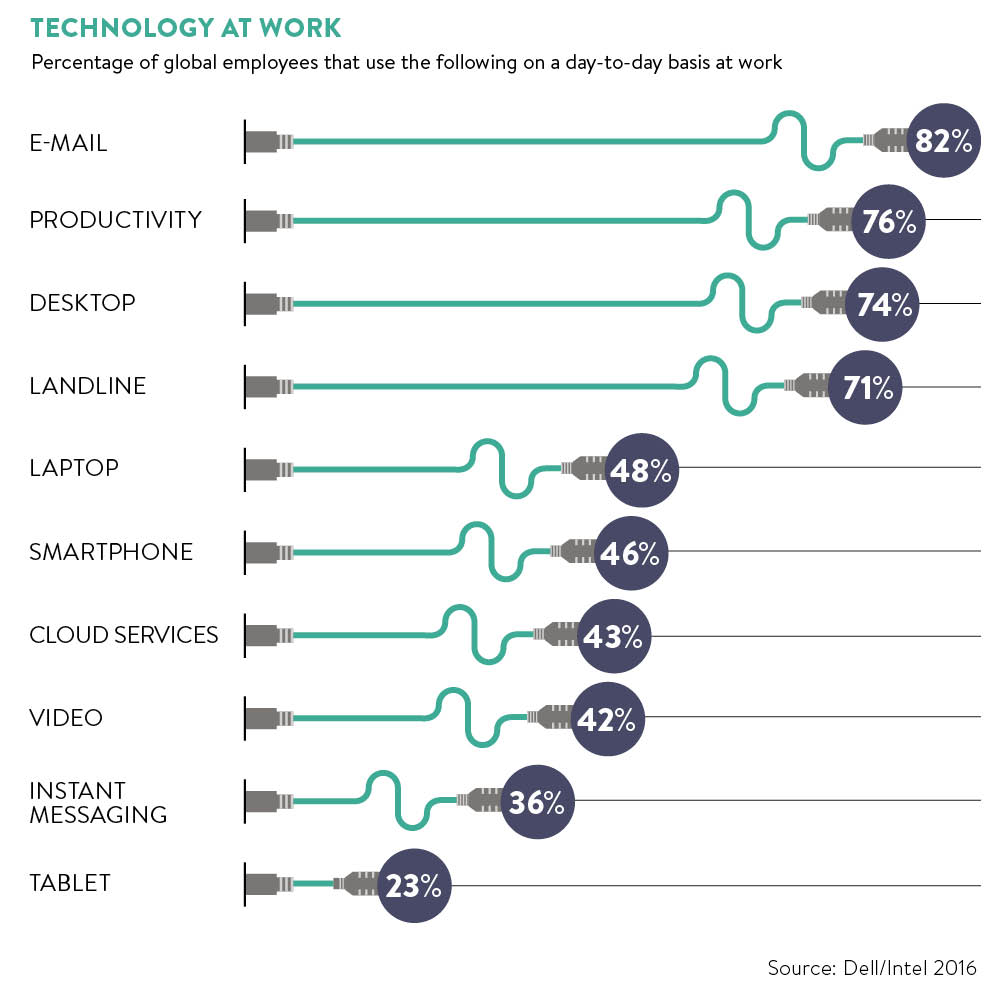

Mobile technology, super-fast broadband and software tools such as Facebook Workplace, Slack and Yammer have already transformed our working lives, by improving efficiency and making it easier to work flexibly on the go and from home.

The pace of change will only increase in future because of further breakthroughs in technology. The challenge for employers is to embrace these opportunities while protecting their staff from the risks.

Technology has brought many benefits, particularly the rise of cloud-based software that has improved collaboration and sharing.

Kathleen Saxton, chief executive of recruitment firm The Lighthouse Company and founder of executive mindfulness practice Psyched Global, says: “We utilise many of the new services, especially Slack for allowing our team to read all the latest non-sensitive information about a client, WeTransfer for creative work files of candidates, Zoho for booking Psyched [psychotherapy in the boardroom sessions] and all the video conferencing you need to ensure everyone can be in critical meetings.”

Mr Hirst, whose agency uses Office 365 software for collaborative working, says: “My big hope is that these tools attack the legacy of presenteeism [in the workplace].”

It is very important that people maintain perspective and give themselves time and headspace on a daily basis

Taher Behbehani, chief digital and marketing officer of BroadSoft, a cloud-computing software business, says demand for more flexible, remote and collaborative working has come from a groundswell of digital natives – a new generation that expects to use the latest smartphone and apps from any location, at any time, and using any device.

However, one of the downsides of this easily accessible, always-on mobile world has been people working excessive hours inside and outside the office.

Mr Ely says: “Employers should ensure that performance and productivity are not measured by being constantly accessible, and that being seen to be permanently available doesn’t replace the importance of doing a good job.”

Some staff still find it hard to take a break because of “FOMO” – fear of missing out.

Mr Krichefski concedes: “It is very difficult to ‘switch off’ these days with mobile phones and social media notifications constantly pinging.” But he warns: “If we do not proactively manage this, it can create stress and other mental health issues. It is very important that people maintain perspective and give themselves time and headspace on a daily basis.

Solutions

MediaCom uses an app, called Blend, to help staff and their line managers to discuss the right work-life blend to enable appropriate working rules of engagement for the individual. Mr Krichefski says: “It is used as a great framework for the discussion. It works to formalise that blend for each individual.”

A lot of companies have launched wellness initiatives to inspire staff and avoid the risk of “burn-out”, as Mr Hirst puts it. “We can’t expect our people to be productive when tethered to the office 24 hours a day,” he says. “They need separation from their ‘CrackBerries’ to rest their brains and bodies.”

Maintaining a healthy work-life balance is a particular problem for senior executives, according to Ms Saxton.

She cites a report from earlier this year by the Chartered Management Institute which found the majority of UK managers spent an extra 29 days annually working outside office hours, more than cancelling out their annual holiday entitlement. “This is where the trouble starts,” she says, recalling how one client with two small children recently confessed to her he was working an 80-hour week and had not had an uninterrupted bathtime with his family in four years.

Some executives extol the benefits of a “techno Sabbath”, a period of 24 hours or longer, usually over a weekend, where they will log off.

Mr Hirst says: “On a personal level, I’m trialling some initiatives where I’m physically removing technology from my vicinity for defined periods of the day so that I can think. I know others who create a folder in their e-mail that automatically collates all messages on which they were just a ‘cc’. We have to change the perception that a day spent responding to e-mail is a good day’s work. It’s not.”

Part of the problem is the continuous stream of information that many people face in the workplace, according to Mr Behbehani, who says companies are introducing siloed, enterprise messaging apps and other tools to act as a filter.

Work does sometimes require people to be contactable at unusual hours, but Ms Saxton’s recommendation is to tell clients “if it really is that important, they can call me on my home line”. That makes people reappraise the urgency of their call. “Reminding each other we are humans appears to be the most successful boundary setter I am aware of,” she says.

Generational divides

Mr Ely says different generations may have different priorities and expectations about flexible working and their own work-life balance.

Millennials, those who came of age after 2000, “may come to expect a blurring of work and home life, and take it in their stride, while the older generations may be less willing to give up their personal time for an always-on culture”, he says. That is a reason why employers must be wary of imposing a one-size-fits-all policy, Mr Ely believes.

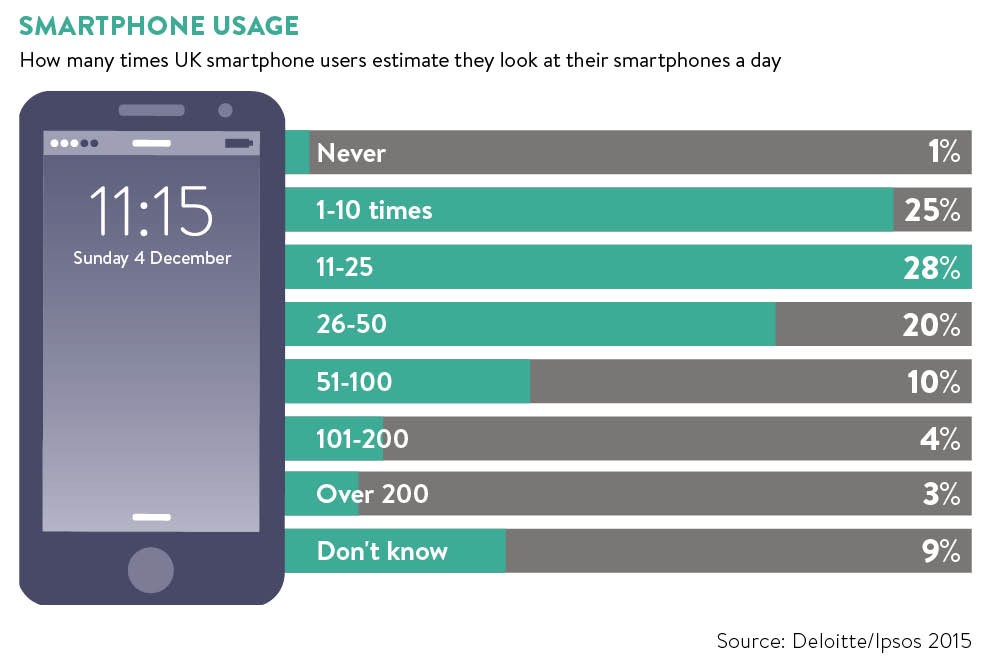

Arguably, it is millennials who grew up with the internet and need the most help in setting boundaries about work, managing stress and switching off their smartphones.

Ms Saxton points to the Mental Health at Work Report 2016, a survey of some 20,000 workers by the charity Business in the Community, which found only 17 per cent of 18 to 29 year olds described their mental health as very good, compared to 32 per cent of 50 to 59 year olds.

She says many organisations have been better at managing the physical health of their employees through gym subscriptions, exercise classes and health checks than investing in mental wellbeing.

When The Lighthouse Company polled more than 600 UK media executives for its 2016 New World Talent Survey, over half of respondents said their organisation could do more to provide “mentally stimulating” services such as coaching or positive psychotherapy sessions. Ms Saxton says too many companies have only addressed this need “after a tragic incident within their business or a pattern of red flags”.

When employers look for best practice, Silicon Valley is seen as a role model because fast-growing companies such as Google and Facebook have fostered a culture of relentless innovation within an environment that offers flexible working, wellness initiatives and other perks such as free food.

Sceptics say complimentary meals at all times of the day encourage staff to work long hours in the office. However, Mr Hirst sees benefits after a recent visit to Google where he spent time in its communal eating areas. “I saw something that the bean counters wouldn’t be able to quantify – lots of connections, conversations, ideas, friendships,” he says. “They are the building blocks of a successful, performance culture.”

In an increasingly digital and automated workplace, we must not forget the human dimension.