In the biscuit aisle of a whole foods market in North London, a tub of Livia’s Kitchen moreish Raw Millionaire Bites sells for £4.99.

Though the packaging is emblazoned with what the sweet treat doesn’t include – refined sugar, gluten or dairy – Olivia Wollenberg, the founder of the popular food brand and the author of a new book of the same name, will tell you that from a business perspective, it’s far more important what actually is included in her products.

“I always tell people that, yes, my products are ‘free from’ and you’ll find them in the free-from aisle, but it’s more important what the products are made with, ingredients you can actually pronounce, and that they taste better than the conventional alternative.”

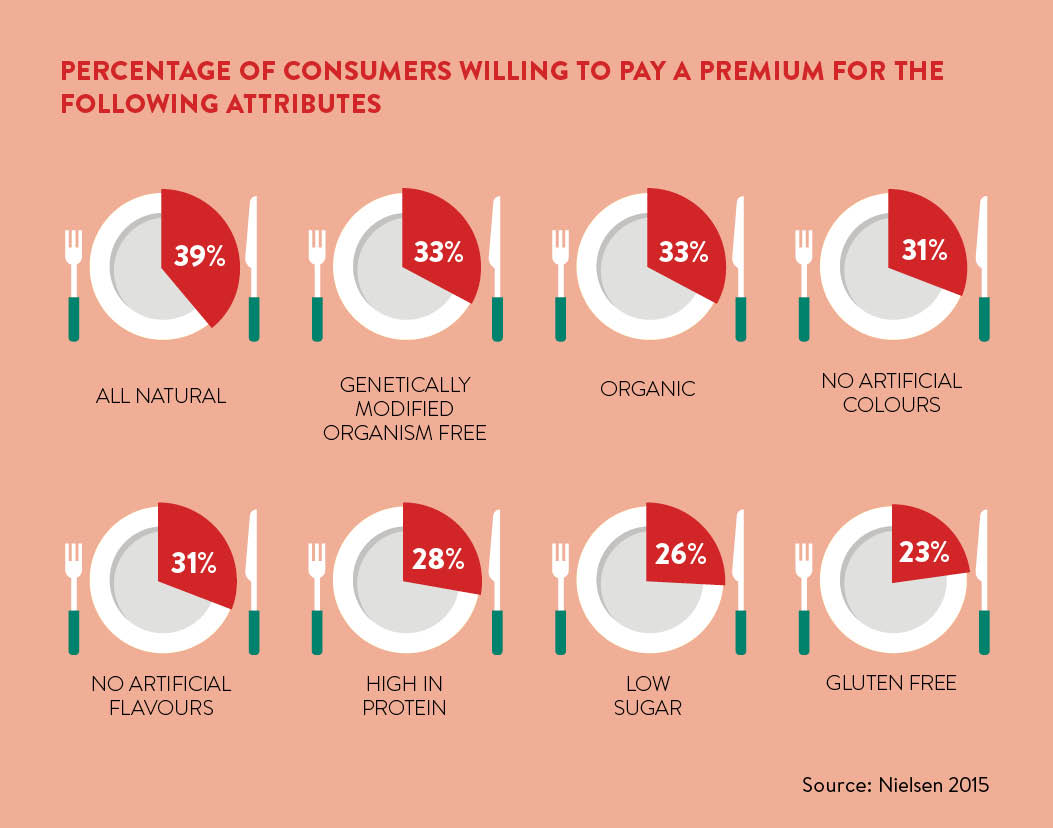

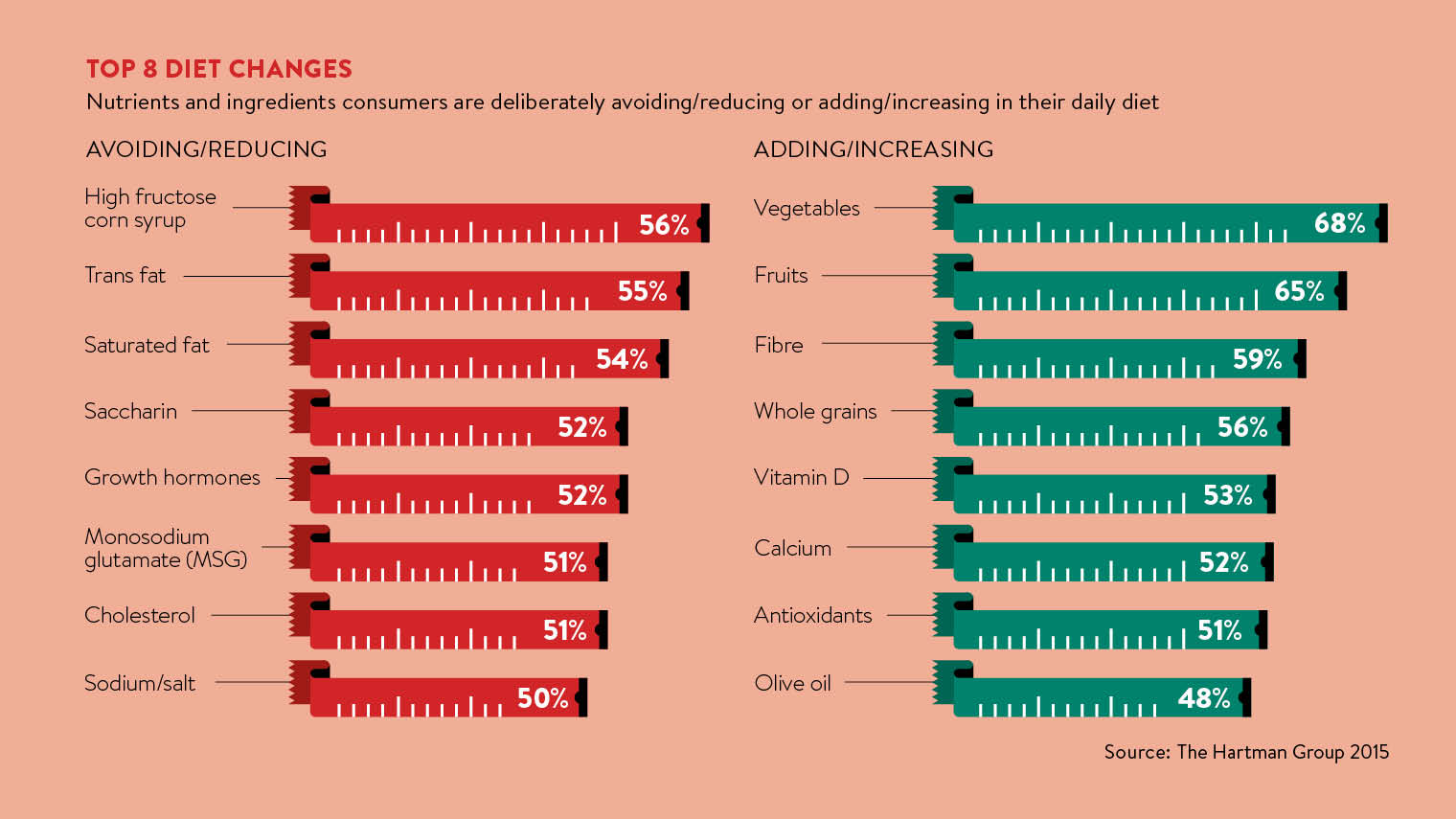

Click here for the full infographic

The ‘wellness’ market

Livia’s Kitchen is just one successful example of the hundreds of brands saturating the so-called “wellness” market in the UK. Research from industry analyst Mintel released in January found that the value of the free-from food sector reached £470 million in 2015, with a projected growth of 43 per cent by 2020. With the most commonly avoided food categories including red meat, gluten and dairy, the report noted that 37 per cent of respondents reported that they or a member of their household avoid a certain food group due to either medical or lifestyle reasons.

With so much enthusiasm for wellness trends across the UK, it seems a promising destination for food industry players seeking new opportunities and added value. But there are risk factors associated with trying to cash in on a market segment that, in many ways, is defined by trendiness, aspiration and the constant search for the next so-called superfood. How can you ensure a safe investment when the very definition of wellness changes so quickly?

Though people trying to watch what they eat in the name of health is nothing new, it’s essential to understand that the current wellness trend is different from its predecessors, says David Jago, a food sector analyst at Mintel. He says the two main differences – an emphasis on “real foods” and the role of social media – are essential for new players to understand if they want to resonate with the current market.

“First there’s been quite an important shift away from the negatives of healthy eating and much more towards the positives. There is much less focus on fat free, very low calorie, sugar free and much more focus on naturally better-for-you ingredients,” says Mr Jago. “The other thing that’s really changed is the influence of social media and connectivity. These ideas spread much quicker, products become available more quickly, consumers are reading about it more than they used to. So the influence of bloggers in this space is really important, particularly if you’re talking about millennial consumers.”

Ms Wollenberg’s brand, which she describes as “sweet treats and desserts with a nutritious twist”, is a perfect case study of what happens when a brand resonates with wellness consumers both online and off. After winning a business grant, she started selling her healthy crumble in Selfridges in 2014 and then quickly expanded to a wider range of non-refrigerated products with a longer shelf life, which she says were easier to scale.

Around this time, she began promoting her brand’s journey on a blog and Instagram, where she has nearly 100,000 followers. Now present in leading premium and health food retailers, she hopes to expand to mass-market supermarket chains in the near future. As her rapid success has proven, there is room for significant growth in the sector and that it’s not just limited to a tiny niche.

[embed_related]

Unpredictable tastes

Lauren Armes is the founder of Welltodo, a media company turned consultancy that works with wellness brands and startups that are trying to break into the industry. Having last month hosted the very first Business of Wellness Summit in London, which was attended by 500 in the industry, Ms Armes says there is no doubt that wellness is big business. However, there is a serious need for market players to understand the customers they are dealing with are willing to do more work and research to find what’s right for them than in other sectors.

“We’re seeing a number of venture capital and private equity firms that are honing in on this space, and really specialising,” says Ms Armes. “Meanwhile, consumers really want to feel empowered to decide what’s best for their bodies. For new brands there is an interesting strategic battle happening between educating the consumer around your product’s benefits without becoming so preachy you move away from the joyous aspect of wellness. Consumers don’t want one size fits all – they want to dictate their own journey.”

Indeed, while social media influencers certainly have a large sway over what gets popular and what doesn’t, it can still be very difficult to predict what a majority of consumers will take up. For example, leading British wellness bloggers Hemsley & Hemsley predicted that bone broth, which aids digestive health, would take off in 2015, but as Euromonitor reported: “This failed to appeal to the wider UK consumer base in the same way as breakfast smoothies, and certainly saw little uptake in packaged food and beverages.”

Ms Armes says this proves industry hopefuls must be aware of the line between consumers, who are purists and will go out of their way for an ingredient or product, and ones who simply want to integrate more easy, healthier products into their lives. It’s the latter group that will lead to mass market successes, such as coconut water, which is reportedly worth £100 million in the UK.

Consumers don’t want one size fits all – they want to dictate their own journey

“In terms of the scalability of a product like bone broth, it can be quite difficult because similar to cold pressed juice, it’s best consumed when made fresh,” says Ms Armes. “It also has quite a niche benefit that people don’t necessarily understand yet. That’s very different from something like coconut water, which has really taken off because the marketing message that it’s a better form of hydration than a sugary sports drink is easier to convey.”

Another potential risk factor is the wellness backlash, a marked media trend in recent months with columnists, specialists and even the parody Instagram account Deliciously Stella poking fun at “clean eating” and “wellness” bloggers such as the hugely popular Deliciously Ella, who extols the virtues of avoiding certain foods.

As The Sunday Times Magazine columnist India Knight wrote earlier this year: “An increasing number of young people are adopting restricted ways of eating for no other reason than fashion. If you look at what normal people eat, a chasm opens up.”

In order to be successful to a broad base of consumers, wellness absolutely has to taste delicious

However, Mr Jago doesn’t see this commentariat as posing much of a threat to the fundamental shift in attitude that has happened around wellness. He says: “Some of [these trends] will be faddish, but the fact is that the consumer is much more open to a much wider range of ideas and range of ingredients and their benefits than ever before. They’re curious and they’re prepared to investigate.”

Ms Wollenberg, who is as much a businesswoman as she is a blogger, says that for market players looking to get involved, the key is thinking differently and not forgetting, in order to be successful to a broad base of consumers, wellness absolutely has to taste delicious.

“You can come in and say, ‘I’m doing a raw cake company’, but there are so many people who are doing raw cakes – what is it that’s different about yours?” Ms Wollenberg asks. “You also need to spend a lot of time in making sure and developing a product which tastes as good, if not better, than its original version.”

The 'wellness' market