One of the biggest threats to our health is cardiovascular disease or CVD. It is the number-one cause of death globally, but many of the biggest risk factors for CVD come from our lifestyle choices. According to the World Health Organization, most cardiovascular diseases can be prevented by addressing risk factors, such as tobacco use, unhealthy diet and obesity, physical inactivity, high blood pressure, diabetes, and raised lipids.

An American Journal of Cardiology study on the value of even minimal exercise in decreasing risk for CVD found that running, even for just five to ten minutes a day, is associated with markedly reduced risks of death from all causes of cardiovascular disease.

In the last ten years, doctors have increasingly called for greater use of statins, the most common preventative medicine against CVD. The clamour reached a crescendo after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the body responsible for clinical guidelines, recommended patients be prescribed the drugs even if they only have a 10 per cent risk of developing CVD in the next decade.

But the challenge of motivating healthy lifestyles remains. Fitness apps for smartphones have proved to be among the most popular technology for encouraging a healthier lifestyle. From MyFitnessPal to the NHS’s Stop Smoking app, there are now easy ways to motivate and monitor a heart-healthy lifestyle.

For example, one of the main risk factors for stroke is atrial fibrillation (AF) because the irregular heartbeat caused by AF makes the blood flow more turbulent, which can sometimes cause a small clot. If this travels to the brain, it can cut off part of the blood supply and cause a stroke.

HOME MONITORS

Traditionally patients have been diagnosed with AF in hospitals or clinics, but a company called AliveCor recognised the potential for people to screen for AF at home, and developed an app and mobile phone attachment to detect the condition by monitoring the patient’s heartbeat.

Matthew Fay, a GP with a special interest in cardiology and former national clinical lead for AF, currently runs a service using these products to detect arrhythmic cardiac disease, irregular heartbeat or abnormal heart rhythm, with symptoms including palpitations, dizziness, fainting, shortness of breath and chest discomfort. His is so far the only service in the UK to use the mobile app and attachment.

Fitness apps for smartphones have proved to be among the most popular technology for encouraging a healthier lifestyle

The biggest strength of having a mobile phone attachment, he says, is that people very rarely go anywhere without their phone, so the device is usually to hand.

He has had plenty of success using the device and, in one particular case, his patient had experienced symptoms for 17 years, seen three cardiologists in two countries and was told she was mentally ill by one doctor. She was diagnosed with dysrhythmia or irregular heartbeat within five days of using the attachment.

However, as Dr Fay points out, he uses the smartphone technology only on specific cases of patients with intermittent palpitation suggestive of cardiac dysrhythmia. At the moment, he says, wearable technology is unproven in clinical trials, has no cost-effectiveness evidence for health systems such as the NHS and is unlikely to cover large enough populations to make a difference to society’s present cardiovascular disease burden.

“Ultimately prevention of cardiovascular disease is relatively simple and ultimately quite boring,” he adds. “It’s a shame we do it so badly, with such devastating consequence.”

INTERNET OF THINGS

The most common wearable technology for exercise at the moment is the activity tracker. Popular models include the Jawbone, Fitbit and the Nike FuelBand. The devices often work by transmitting information directly to the internet or other devices. This is known as machine-to-machine communication or the internet of things. They may link to a mobile device, such as a smartphone or tablet, where activity and energy consumption, for example, can be monitored or compared.

But such devices are not without their challenges. Tom Dawson, founder of UK wearables development company ResCon, says there are three main issues developers need to deal with when designing wearables.

Firstly, he says: “Before we even start, there needs to be motivation from education, cultural change and sometimes crisis.”

Second is the concern that people will start to focus on the tech at the expense of using their own knowledge and experience. “People cannot rely on wearables or apps to reduce their CVD risk. In the end they need to be relying on themselves. Wearables and apps need to be tools to enable a positive change in lifestyle and subsequently performance in day-to-day life,” he says.

And echoing Dr Fay, Dr Dawson says the third issue is getting over the lack of interest in healthy living.

Wearables are unlikely to be a solution for everyone and are only likely to have a short-term benefit. Dr Deborah Lupton, a sociologist who researches self-tracking and digital health technologies at Australia’s University of Canberra, points out that most people who buy apps and wearables are already interested in voluntarily managing their own health and don’t use the apps or devices for long.

In the end, intuition is sometimes the smartest “app” we have for monitoring our own health. “We need to remember not to invest all our trust and faith in digital devices, and incorporate information from various sources, including how we feel, when monitoring and assessing our health,” she concludes.

WEARABLE TECHNOLOGY TO HELP YOU GET FIT

MEASURING ACTIVITY

Fitbit manages two major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) – inactivity and obesity. The device is not specifically targeted at people at high risk of CVD, but like other activity trackers, it is one of the most commonly used wearables on the market.

The company’s latest update, the Fitbit Force, was launched last October and features an OLED display that shows time and daily activity.

The Fitbit device is worn like a watch or bracelet and transmits real-time information about how much the wearer exercises and sleeps, among other measures of activity. Users can read data about how healthy their lifestyle is by logging into the Fitbit website or the mobile app.

Last May Fitbit held a reported 50 per cent share of the wearables market, selling more than a million bands in the first quarter of 2014.

STEP-BY-STEP MONITORING

The pedometer was dreamed up by Leonardo da Vinci, but wasn’t realised until 1780 when a watchmaker created the first mechanical device that could count steps and measure walking distances.

Popularised in 1960s Japan, the main flaw with the pedometer is inaccuracy. Also cheaters could simulate exercise by tapping or hitting some devices against hard surfaces, thus faking a higher level of activity.

Nowadays it’s common for multifunctional devices, such as smartphones and iPods, to do the job of the old single-function device. Phones contain hardware called an accelerometer, which measures force of movement and relative change in the height of the device to detect a step. Some devices use a co-processor, and combine a compass and a gyroscope with an accelerometer, to improve accuracy.

LISTENING TO YOUR HEART

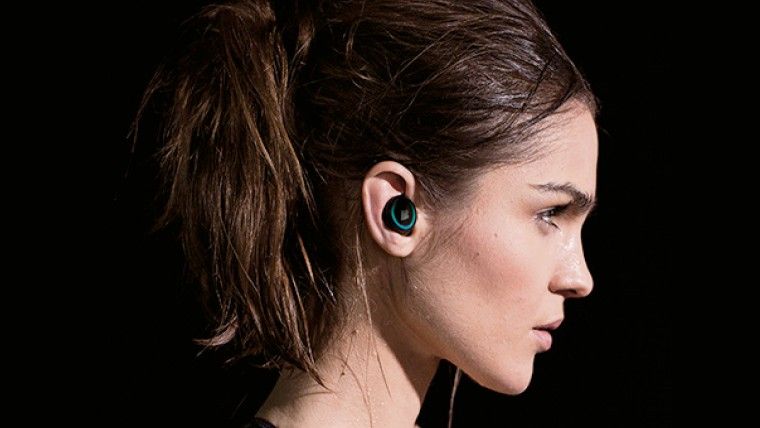

Ever heard the blood pulsing through your ears after a run? The ears are one of the best places on your body to measure heart rate and the designers of new “smart” ear buds have created wearables to do just that.

Smart ear buds sit in your outer ear. From their snug position, they can monitor your pulse and send information back to an app. You can then analyse data about how your heart rate changed during a run, and get the lowdown on distance, calories burnt and how hard your heart worked. They also double as headphones to play music.

LG and Intel both produce smart ear buds. The LG model, HeartRate, offers bespoke in-ear training updates, and the Intel version, co-produced with SMS Audio, is battery free. Another model, produced by Bragi, has four gigabytes of storage space on the device for music files.

TAKING THE PRESSURE

Whether it’s a preventative measure or a way to manage your own health, wearing a blood pressure monitor is now easier than ever. Gone are the days when subjects would be wired up to bulky monitors and checked using huge nylon cuffs.

Wireless blood pressure monitors are now available to use at home and some models can be used for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring as you go about your day. They work by monitoring blood pressure from a device worn on the arm or wrist, and transmitting it wirelessly via Bluetooth to an app on a mobile phone, tablet or computer where you can read and analyse the results. You can even share the results with your doctor.

High blood pressure is a significant risk factor in developing CVD, so monitoring the effectiveness of new medication or a better diet might reassure people that lifestyle changes are having the right effect.