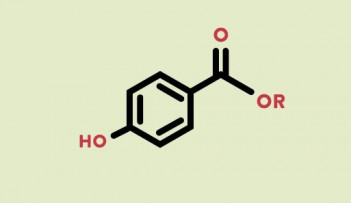

Butylparaben doesn’t quite sell the dream like Scarlet Desire or Wild Ruby, but every day minute traces of the chemical are applied to billions of lips as a constituent of lipstick.

It is a member of the parabens, a clan of chemicals with extraordinary, but approved, presence across beauty products, foods and medicines.

Critics are concerned that parabens could have an effect on estrogen levels and lead to endocrine disruptions that could, in turn, derail the body’s delicate balance of hormones.

Chemicals are all around us, safe and highly regulated according to some; an unnecessary evil to others. But broad acceptance of their everyday role in consumer lives is being challenged as evidence mounts over their desirability in our food and health chains.

The impetus for change comes largely from a public increasingly conscious of their chemical intake

The US retail giant Walmart, which owns ASDA stores in the UK, is pushing suppliers to remove or restrict the use of eight hazardous chemicals from household cleaning, personal care and beauty products.

On the company’s “wanted” poster are butylparaben and triclosan, used in toothpaste clothing, kitchenware, furniture and toys. Safe limits of this gang of chemicals have been set by the US Food and Drug Administration, but the impetus for change comes largely from a public increasingly conscious of their chemical intake.

Calls for tougher regulation

Scientists argue that the presence of a chemical is no automatic cause for alarm, and that trace levels are quickly metabolized and pose no threat. They have a wealth of evidence to debunk danger claims. But for many, the risk feels too great.

Margo Marrone, a pharmacist who founded The Organic Pharmacy, says parabens and phthalates, used in a spectrum of supermarket shelf products and to make plastics more flexible, have been linked to breast cancer and other conditions.

“These hormone disrupting chemicals are absorbed when applied to the skin and can accumulate in the body disrupting our delicate hormone system and propagating hormone related cancers such as breast, ovarian and prostrate,” she adds.

Ms Marrone is not alone in wanting tougher regulations on chemicals as an evidence base grows for their exclusion from the manufacturing chain.

A recent study found that a group of 100 teenage girls experienced a 45 per cent reduction in the level of dangerous chemicals in their body after they took a three-day break from certain cosmetics that were thought to affect hormone levels in young women.

We are exposed to chemicals throughout our daily life and we don’t fully understand the interaction and their impact.

Research leader Dr Kim Harley, of the University of California, Berkeley, says teen girls were likely to have more exposure at a crucial time of their reproductive development, adding: “We know enough to be concerned about teen girls’ exposure to these chemicals.”

The charity Breast Cancer UK (BCUK) echoes the concern, explaining that a group of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC), found in anything from kitchen products to flame retardant in furniture, can promote higher levels of estrogen, so stimulating cell division and increasing the chances of mutations that lead to cancer.

EDCs mimic estrogen and bind to the same receptors triggering a chain reaction that can lead to breast cancer, BCUK claims.

“We are exposed to these chemicals on a daily basis and exposure over a lifetime can be chronic. EDCs can have an impact at fairly low levels and there is increasing research, though more needs to be done, on the cocktail effect with other drugs, giving them an even bigger impact,” says BCUK chief executive Lynn Ladbrook.

Professor Susan Schantz is conducting major research into the impact of chemicals in consumer products at the leading-edge Beckman Institute, University of Illinois. The work, focusing on a range of chemicals that stabilise products and preserve their shelf lives, will go a long way to providing conclusive evidence of their benign or harmful nature.

She says: “Research is growing that suggests pre-natal exposure to phthalates can affect neural development in children, so those with higher pre-natal exposure have been shown to score lower on certain cognitive tests in later childhood.”

Exposure levels vary, often daily, depending on our consumer habits and the jury is out on the health jeopardy caused by mixtures of chemicals, Professor Schantz adds.

An increase in exposure

Chemicals cannot be avoided in daily life and they appear naturally in some foods. But pressure groups are advising a move to organic food, natural cosmetics and avoiding the use of plastics for food storage and microwaving.

Clare Oxborrow, senior food and farming campaigner at Friends of the Earth, says: “It is a hugely complex area, and we are exposed to chemicals throughout our daily life and we don’t fully understand the interaction and their impact.”

“We do know a number of them have worrying properties and have been linked to hormone disruption effects that can go on to cause cancer and other hormone-related diseases. And we know these kinds of illnesses have been increasing over the last few decades with the increased use of some of these chemicals.

“It is very difficult to say this specific chemical is linked to this specific cancer or disease, but there is a general exposure increase and we have always taken the view that a cautionary approach to protect human health and the environment is best.”

The Organic Trade Board, which represents 130 firms, supermarkets and independent retailers, such as Green & Black’s, Yeo Valley and Rachel’s Organics, says the age of organic consumers has shifted from the over-40s to the 20 to 30-year-old age group.

“They are younger and are more interested in where their food is coming from and there is generally more interest in clean, healthy living,” says Catherine Fookes, campaign manager. “No one really knows what these chemicals will do to us long term with the cocktail effect, so we promote a healthier lifestyle and all that goes with it.”

According to the government’s watchdog Food Standards Agency, strict controls protect the public: “There are rules in place which control the risks to consumers from various chemicals in foods. These include contaminants occurring in the environment and through food processing or substances, such as additives, which are added to food for a specific purpose such as food preservatives or sweeteners.”

The corporate world has responded to growing concerns and significant efforts are being made to research chemicals and develop alternatives, while regulators insist that safety checks and procedures are robust enough to protect the public.

5 CHEMICALS IN THE DOCK

01 BISPHENOL A

Found in plastic food and drink packaging, it can leach into food and liquids, and human exposure is widespread. A 2004 survey found detectable levels in 93 per cent of 2,517 urine samples from people aged six and older. Concern has been raised about its impact on behaviour and infant development.

Source: US National Institute of Health

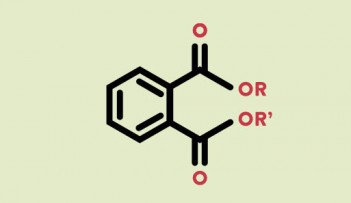

02 PHTHALATES

Additives used in scented products and plastics, such as shower curtains and PVC flooring, these have been linked to child development issues in observational studies. They have also been indicted as a cause of lower libido rates in men and women.

Source: ChemTrust

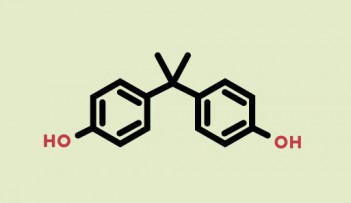

03 PARABENS

Used in cosmetics and food products as preservatives, they have an ability to mimic naturally occurring estrogens involved in breast cancer, it is claimed. Recent research implicated low levels of parabens as having hormone disruption potential.

Source: Environmental Health Perspectives/BCUK

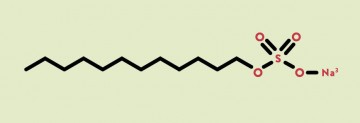

04 SODIUM LAURYL SULFATE (SLS)

Found in personal care products such as soap, shampoo, bodywash, toothpaste and industrial detergent, SLS has been blamed for skin irritation with strong adverse reactions in some people. It is being investigated for connections with premenstrual syndrome.

Source: American Journal of Toxicology/SLSFree

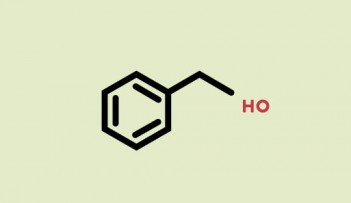

05 BENZYL ALCOHOL

Used in personal care products and cosmetics as a stabiliser and fragrance enhancer, and as an anaesthetic ingredient in over-the-counter medicines, it has been blamed for skin irritations including itching and hives.

Source: Cosmeticsinfo.org/Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology

CASE STUDY: THE HONEST COMPANY

Organic products have been championed by a wide range of celebrities, but actress Jessica Alba went a step further by establishing The Honest Company, selling a range of beauty products.

Organic products have been championed by a wide range of celebrities, but actress Jessica Alba went a step further by establishing The Honest Company, selling a range of beauty products.

But the harsh reality of business has impacted her vanguard action, and lawsuits have been brought alleging some products were not completely natural and its sunscreen was not effective.

The actress turned chief executive has faced claims that a detergent product contains significant levels of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS).

Ms Alba, who has starred in Hollywood movie hits, has vigorously defended her line and the company issued a statement following the claims, denying the presence of SLS, stating: “We stand behind our laundry detergent and take very seriously the responsibility we have to our consumers to create safe and effective products.”

If organic and natural companies take on established firms across a range of products and become a threat to reputation and profit margins, then the reaction will be fierce.

Organic sales in the UK are growing and, after a 12 per cent sales dip following the 2008 recession, organics posted a 4.9 per cent growth last year compared with a 0.1 per cent dip in non-organic sales, according to the Organic Trade Board.

The Soil Association’s 2015 Organic Market Report recorded a 20 per cent rise of organic beauty product sales to £44.6 million and, backed by the Mintel’s 2025 Trends report highlighting that 42 per cent of UK consumers prefer natural and organic products, the landscape appears primed for a series of startups and initiatives.

It is still a fraction of the market – the UK beauty and personal care market generates more than £17 billion in business annually – but, as Ms Alba and The Honest Company are learning, performing on the big stage comes with high levels of scrutiny.

Organic firms have to ensure they practise what they preach and that they comply with the rigorous testing employed by established non-organic companies.