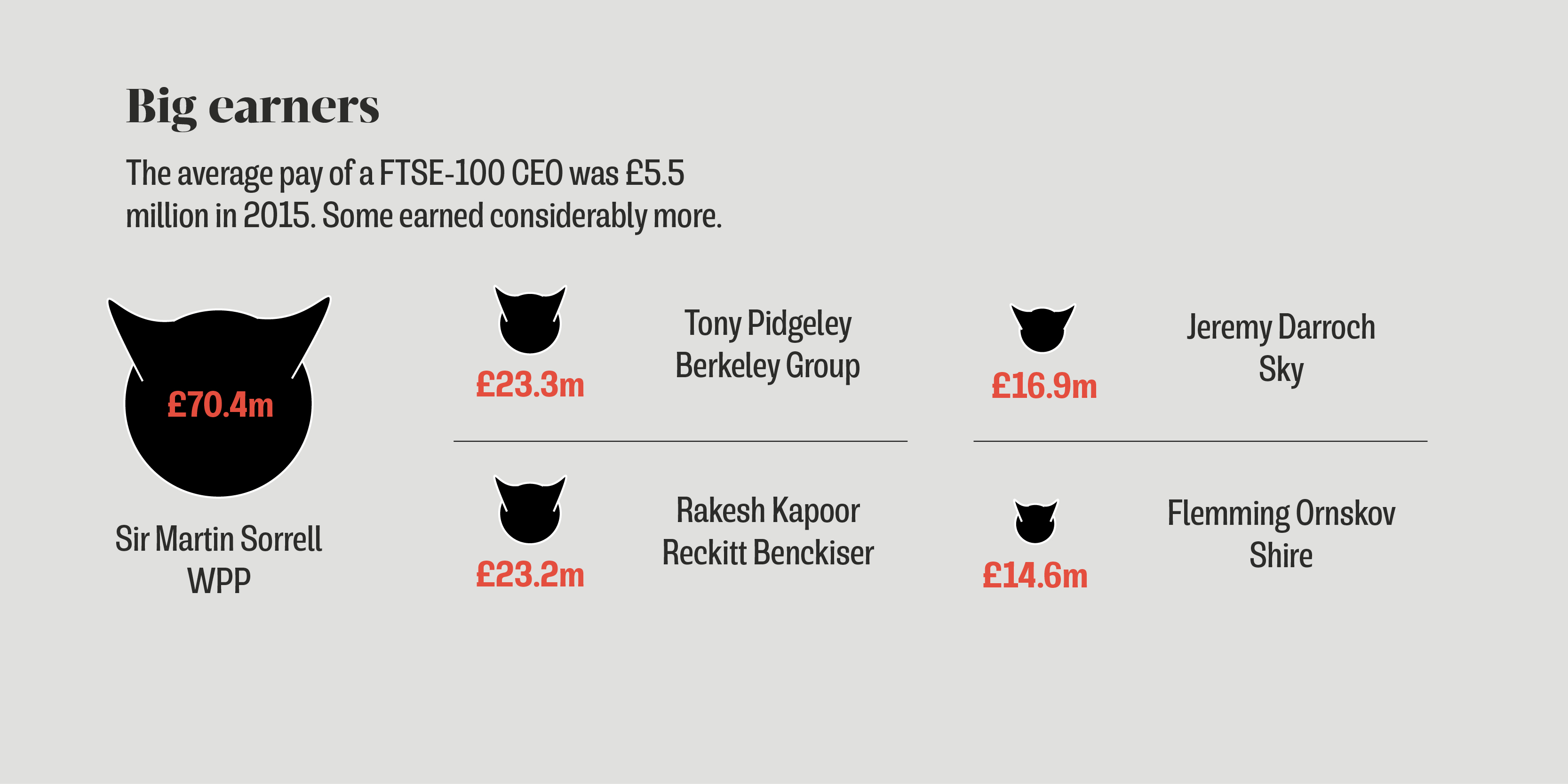

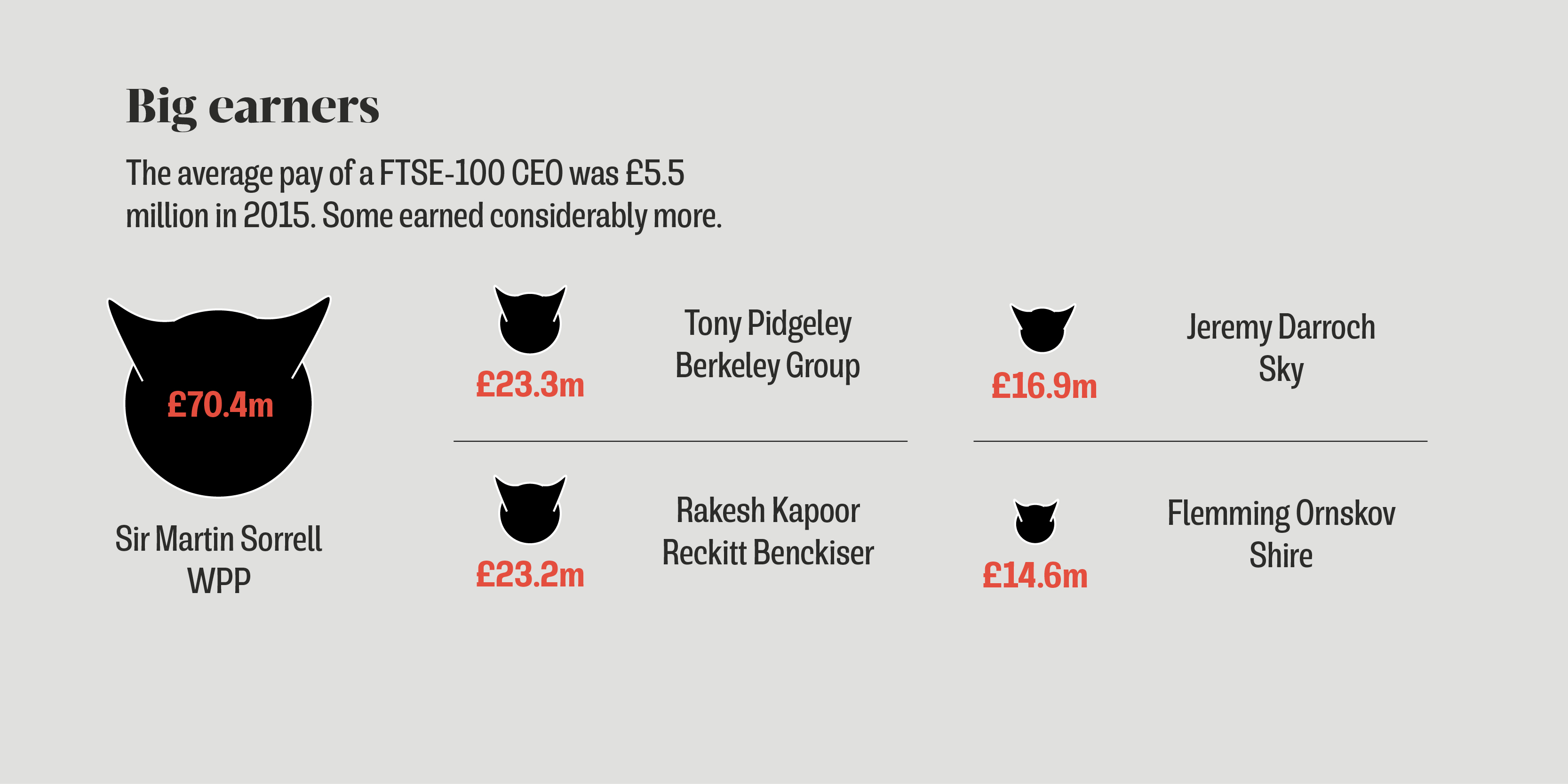

The CEOs of the UK’s largest public companies received a 10 per cent pay rise in 2015, vastly outstripping that of ordinary workers, according to research from the High Pay Centre, a think tank that monitors boardroom pay. The pay packets of FTSE 100 bosses rose to an average of £5.5 million, in 2015, while corporate profits fell by 19 per cent.

High levels of executive pay are hardly new, but the new figures – coming as they do, hot on the heels of the collapse of BHS and the pressure on its billionaire former owner, Sir Philip Green – crystallise the challenge for a government that is trying to pitch itself as a force for social equality and justice.

Prime Minister Theresa May, during her brief and successful campaign for the Tory leadership, promised to push through boardroom reforms, including putting workers on company boards, and making shareholders’ votes on executive pay legally binding. Currently, shareholders can express their views on how much companies’ top brass get paid, but their votes are only advisory. Other measures under discussion include the compulsory publication of the ratio of boardroom remuneration to shop-floor pay.

As boardroom pay rises, figures from the Office for National Statistics show that average wages across the country rose by around 2 per cent, after falling consistently since the financial crisis. Analysis in July by the Trades Union Congress showed that in real terms – i.e., taking into account inflation and rising living costs –wages in the UK have fallen by 10.4 per cent since 2007. In Europe, only Greece, which is still locked in a brutal economic crisis, experienced a similar drop.

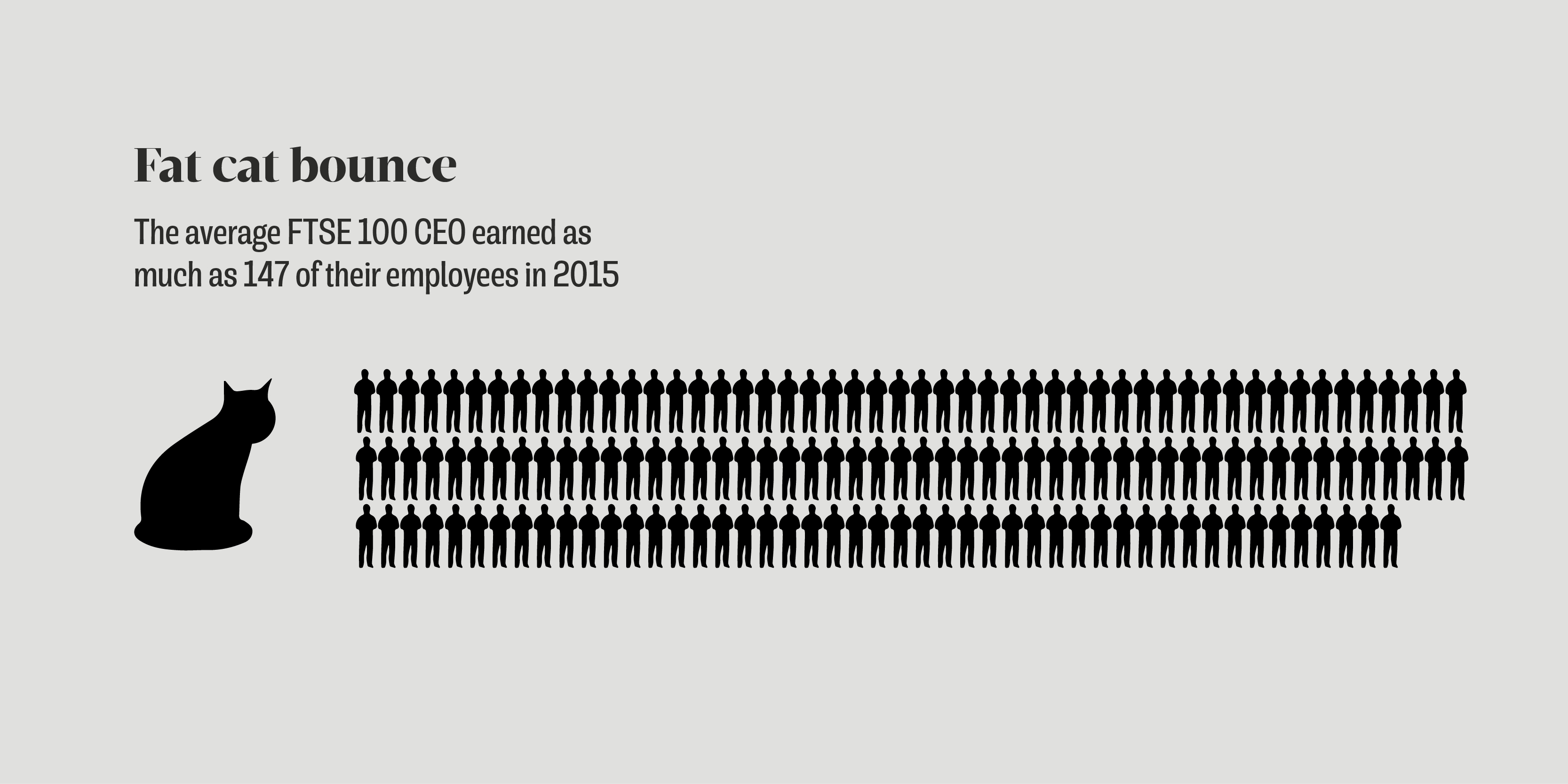

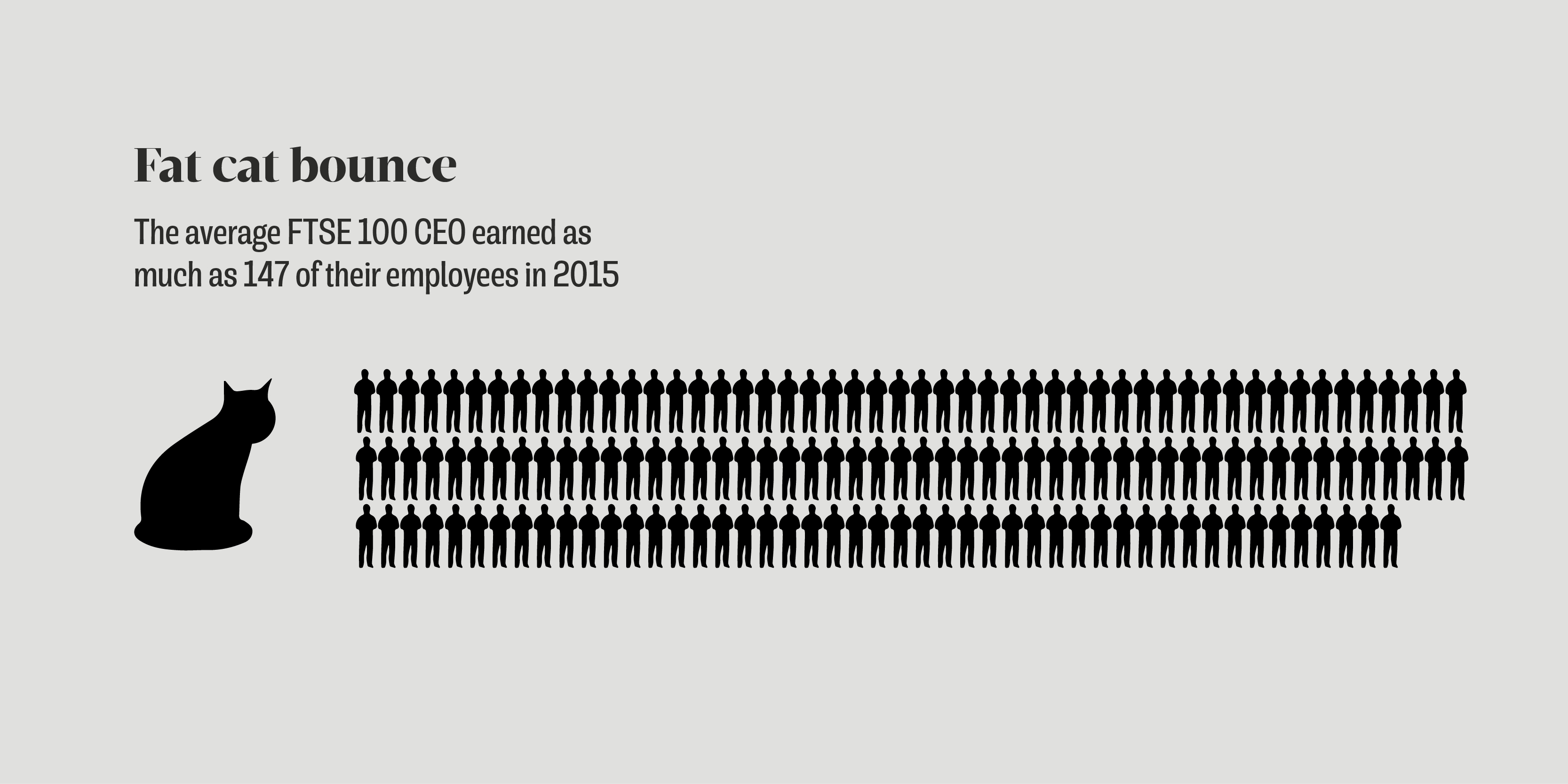

The average FTSE 100 CEO earns as much as 147 workers, according to the High Pay Centre’s research. While inequality is a growing global challenge, the gulf in remuneration between executives and ordinary employees, particularly in listed companies, is far greater in Anglo-Saxon economies, and in the UK in particular. How, then, did Britain get to this point?

“The short answer is that from the 1980s the political class prioritised capital over labour. The latter saw their rights and relatively stable working life disappear which countered, at least for while, stagnating profits – to the advantage of investors,” says Lorraine Talbot, professor of company law in context at York Law School.

“Executives are employees, but they have always been entwined with investors and mechanisms were put into place to ensure that this latter allegiance overrode all others. These mechanisms included high executive pay which was aligned with share performance and the promotion of shareholder value as the defining goal of business.”

High executive pay tells us that profits are being delivered to shareholders and employees here and overseas are paying the price, hence inequality and poverty

As executives’ incentives and continued employment were directly linked to the narrow profit goals of shareholders, they were encouraged to reduce costs – meaning wages – and pursue profits through financial engineering. Investments in productive capacity suffered.

“Examples of this [are] using company money to repurchase shares, investing in financial companies, or selling assets to create profits – like Philip Green. High executive pay tells us that profits are being delivered to shareholders and employees here and overseas are paying the price, hence inequality and poverty,” Talbot says.

Reforming shareholder capitalism

The pay gap, then, is not just due to the greed of “fat cats”, whose lifestyles and jaw-dropping pay packets make them easy fodder for newspapers, and a convenient shorthand for inequality. It is the entire premise of shareholder capitalism and the ideologies that support it that need to be reformed.

“This has operated with a self-perpetuating mechanism that has boosted executive pay packages and bonuses, and has contributed to a radically increased gap between what the average worker earns and what the average CEO earns. It is this kind of overall calibration of the model that has led to the increasing gap,” says Andreas Kornelakis, senior lecturer in international management at Kings College London.

“It requires a radical rethink of what companies have to offer, what to expect business to do in contemporary society. Is it just high profitability – that’s the narrow understanding, giving back high dividends and stock prices to shareholders?

“Or is it that companies need to take a long-term view and incorporate a larger set of objectives, including environmental and financial sustainability, including satisfying other stakeholders including employees; including treating consumers in a fair way, and more broadly contributing to prosperity in wider community and society? That requires a radical refocusing.”

Voluntary measures, and “corporate social responsibility” initiatives are unlikely to deliver the level of change needed to truly reform the existing system, according to Kornelakis.

“What we have seen is that if business is left to its own devices, it does not recalibrate itself towards these aims,” he says.

Companies have shown themselves adept at ducking regulation too. When the EU capped bonuses at banks after the financial crisis in an attempt to reduce bankers’ incentives for taking risk, many companies simply found loopholes, restructuring their pay packets to meet the letter, not the spirit, of the law.

Outside of the banking sector, most initiatives in the UK have been voluntary, and focused on transparency – apparently in the hope that forcing companies to report on their inequities will shame them into reform.

“For the last 30 years the government has viewed disclosure as the answer to all corporate governance problems and it drives me mad,” Talbot says. “It is a manifestation of neoliberalism and an aversion to regulating business. It assumes that more information will allow the market to address its own problems. It’s sort of based on Judge Brandeis’s famous adage that ‘sunlight is the best disinfectant’ but as I often say to students, only a pre-feminism man could think that it was sunlight that did the cleaning.”

Low pay nation

What is startling about the UK’s acute low pay problem is that it is not the consequence of low employment. In fact, the unemployment rate is back to pre-financial crisis levels of less than 5 per cent.

“You look at Greece, and you’ll see that employment’s fallen. But in the UK, employment’s risen, and real pay has fallen,” says David Spencer, professor of economics and political economy at the University of Leeds. “From an economics point of view, you’d expect higher employment to feed through to higher pay, but it’s just not happening.”

Self-employment, involuntary part-time work and irregular forms of work, such as zero-hours contracts, have all increased. This has combined with cuts to in-work benefits, feeding through into poverty for people in work, as well as those out of it.

This not only demonstrates the flaws in the UK’s current economic model – research released in July by the Boston Consulting Group showed that the country is poor at translating its economic growth into wellbeing – but also highlights a real risk for continued growth.

Survey after survey shows that workers in the UK feel insecure, stressed and demoralised, which is feeding through into lower productivity. At the same time, household finances are stretched to breaking point.

For a consumer-focused economy, this is bad news.

Households can only go on spending so much. Once their savings are zero and they can’t borrow anymore, that’s when their spending stops. And the economy will stop.

“If you look at drivers of growth at the moment, there’s no growth being driven by exports. The budget deficit is falling, so the government is not contributing to growth, indeed it’s restricting growth through reduced spending. The major source of growth in the UK is coming through higher household consumption. How are households spending more? They’re running down savings,” Spencer says.

“Households can only go on spending so much. Once their savings are zero and they can’t borrow anymore, that’s when their spending stops. And the economy will stop. When you bring Brexit into the mix, that’s not good.”

Initiatives like the new living wage, which will effectively bring minimum wages up to £7.85 across the UK, and £9.15 in London, only impact a small number of workers at the very bottom of the ladder. What is needed could be a significant shift in policy, and a break with the fiscal consolidation approach taken by the Cameron government.

Lowering VAT, increasing income tax thresholds or even ‘quantitative easing for the people’ – essentially handing out cash to households – have all been put forward as solutions by economists. All would require a quite fundamental change of gear by the current Tory cabinet, but business as usual is not really an option.

“It’s difficult to come up with mainstream proposals,” Spencer says. “There’s a rhetoric, and then there’s the question of whether there’s the policy to back it up.”

Reforming shareholder capitalism