Getting into Atmeh was simple. Pay a smuggler and scramble over the hills and farmlands, or take a single-track road down to a river where small boats were dragged back and forth using ropes; smuggling fighters, food, weapons and journalists into the Syrian warzone. Then make your way to the small, nondescript area set among the olive trees.

To this day there is a large camp of displaced people in those trees. It started as a makeshift place to hide during 2012, when northern Syria was wrestled from government control by the rebels and the seesaw fighting and government bombing campaigns forced thousands of people to flee. Back then, nobody thought the war would last much longer.

Firas al-Absi was in Atmeh too. A Saudi-born Syrian jihadist with big ambitions, he came to build his own empire. The power vacuum of the war allowed men who had previously lacked agency in a rigid, hierarchical society to get a taste of power. Hundreds of small katibas — fighting cadres — were created. Their leaders were not strategists, they were farmers or teachers. Each gathered a collection of men and began to fight, becoming the king of his own small domain. Firas was no exception, but his aims were larger.

[tweetThis text=”They were dealers in violence, and able to exploit the naivety of foreign arrivals in Northern Syria”]

Firas, who had previously met with al-Qaeda leader Abu Musab az-Zarqawi in Afghanistan, began to build an army of jihadist fighters in this small corner of the Syrian countryside. Many of them were from Belgium and England. Through groups such as Sharia4Belgium and the followers of radical British preachers like Anjem Choudary, he recruited young men who came to wage war in the country.

Jihadist scholars have long seen Europe as a soft target. US security policies in the post-9/11 years made the country difficult to access. Attacking Europe came with the added incentive of further polarising often fractured societies by preying on and recruiting marginalised Muslim youths in these countries — a strategy first tabled by Osama bin Laden’s acolytes in 2007.

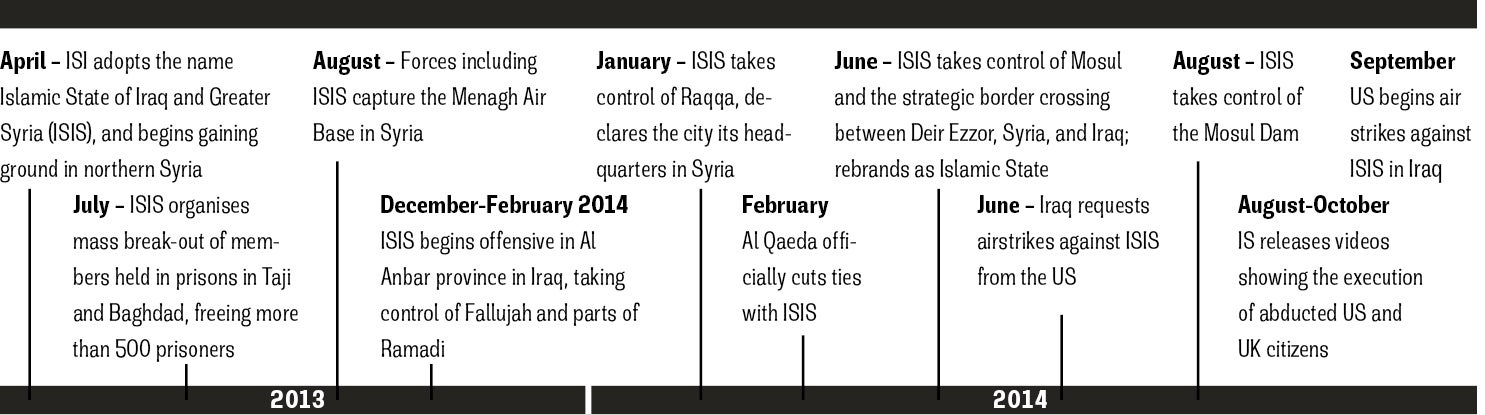

ISI Timeline of terror

2004-2013 timeline

Over the coming years, this small army would go on to dominate world headlines, helping to bring the Syrian civil war to the West and the West back into Iraq and then into Syria. The public executions of American and British hostages would be first, at the hands of a British jihadist, Mohammed Emwazi — the so-called “Jihadi John” — masterminded by Firas’ older brother, Amr al-Absi. Attacks on the streets of Paris and Brussels followed.

Richard Barrett, a former British intelligence officer who now specialises in counter-terrorism at the Soufan Group, tracked the Absi brothers. “They were dealers in violence, and able to exploit the naivety of foreign arrivals in Northern Syria to capture the Belgian ‘franchise’,” he says.

The battle with the so-called Islamic State is as much one of symbols and words as it is one of airstrikes and boots on the ground — on both sides. The death of Emwazi in November 2015 was celebrated at the highest levels of government in the US and the UK; when Amr al-Absi was killed in March 2016, it passed without comment. This rhetorical war has fuelled a narrative of a “clash of civilisations” and increased the divisions within European society, creating a feedback loop of ostracisation and radicalisation. The path of Firas al-Absi, his brother Amr, and the men they led and worked with, is the story behind the realpolitik, rhetoric, and violence.

Raising the flag

“He was a good person and had a brave heart,” says Abu Ahmed, who fought with Firas al-Absi in the early stages of Syria’s civil war. Firas was uncompromising in his religious beliefs but had a reputation for fairness. From an early stage, he was intent on internationalising the conflict. Recently obtained IS personnel files show Firas was recruiting foreign fighters as early as April 2012, long before it burst into the international consciousness.

On July 19, 2012, Firas’ men raised al-Qaeda’s flag over the border crossing with Turkey at Bab al-Hawa in northern Syria, causing a rift with other rebels. The leader of the local Free Syrian Army group said at the time: “al-Qaeda is not welcomed by us.”

That same day Firas’ men kidnapped two journalists, John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans, as they crossed illegally into Syria near Bab al-Hawa. The journalists’ stay was brief and violent; they were rescued a week later by the FSA. In interviews after the fact, they described as many as 15 Britons in the group that held them.

The following month, FSA units took back the border crossing. Firas was killed. Five months later, the commander of the rebel group responsible was assassinated in retribution.

As Firas was fighting on the border, his brother Amr was running a jihadist group in Homs, the city in western Syria that was for years the chaotic heart of the struggle for the region.

In 2007, Amr had been detained in Syria’s Sednaya Prison, where he had developed a reputation as a hardline Salafist. A jihadist who knew Amr from their time in Homs said that his years in prison had done nothing to enhance his understanding of religion, yet everything to worsen his extremism and coarseness. He was released in 2011, under Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s amnesty of Islamist detainees.

Amr was incensed by the death of his brother. He combined Firas’ group with his own and began to grow their ranks. Houssien Elouassaki, Sharia4Belgium’s now-deceased former leader and an admirer of the brothers, came to Syria and became Amr’s second-in-command, helping to open their ranks to Belgian and Dutch volunteers.

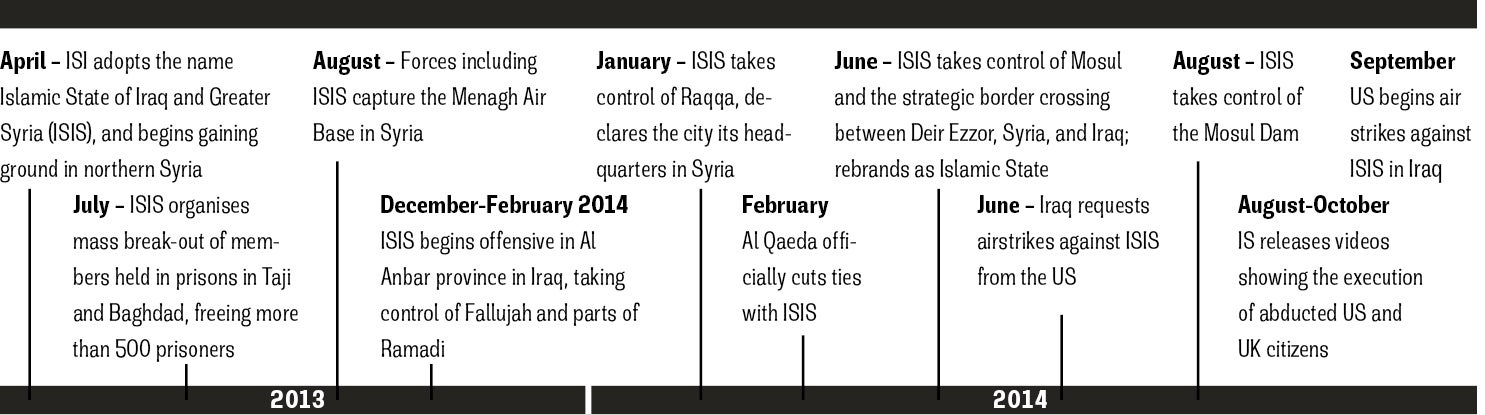

2013-14 timeline

‘The Beatles’

The group became a lightning rod for foreign jihadists looking to join the fight in Syria. That year, Mohammed Emwazi, a young Kuwaiti-born British citizen, would land in Atmeh and fall in with Amr. Emwazi would go on to shock the world when he was unmasked as “Jihadi John’.

Emwazi later coaxed two of his friends from West London — Alexanda Kotey and Aine Lesley Davis — into joining him in Syria. Together, they, along with a British fighter who remains unknown, became the jailers macabrely dubbed “The Beatles” by their captives. The group quickly began taking hostages. On Thanksgiving 2012, John Cantlie and fellow journalist James Foley were driving to the Turkish border from Binnish when masked men grabbed them. A Syrian source said his early inquiries into their abduction resulted in terrified Syrians telling him that “this was Absi and his men, don’t ask me about this again”.

This was only the start of their torment, which would end fatally nearly two years later for Foley and continues to this day for John Cantlie. The group kidnapped British aid worker David Haines and his colleague four months later in the same area.

IS rises

In early 2013, Haji Bakr and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leaders of what is now known as IS, slipped into Syria from Iraq. At the time, they were still working under the auspices of al-Qaeda’s Iraqi offshoot, the Islamic State of Iraq. They met with Amr al-Absi, attracted by his cadre of foreign fighters.

By the middle of 2013, Bakr and Baghdadi had control of most of northern Syria. Amr pledged allegiance to Bakr and Baghdadi in secret, according to IS leaks released by the insider Twitter account @wikibaghdadi.

The account of their meeting also claims that Amr was the one who pushed Baghdadi to formulate a plan to create an “Islamic State,” or caliphate. For his loyalty, Amr was rewarded with the title of Emir of Aleppo, the highest position in the city and its environs. It was in this role that he orchestrated and supervised the kidnapping of dozens of foreign hostages and then detained them in the Aleppo hospital complex, which they converted into a jail. The kidnapping of foreigners reached epidemic proportions in the country; “The Beatles” were responsible for at least two dozen of them.

Conditions in the prisons run by Amr were brutal. Abu Safiya al-Yemeni was held for 70 days, under Amr’s direct orders: “I was working in a hospital in Aleppo. IS asked us to go and speak with Abu Atheer, a young man who did not seem to be wise, and with them there was a Sharia judge… He was the wali of Aleppo, a kid.” he said after his release. A foreign hostage also said after his release that a senior person, likely Amr, visited the cell they were held in several times, personally overseeing their detention.

As Amr’s star began to rise, so too did the flow of foreign jihadists, to his ranks. Najim Laachraoui, a young Belgian of Moroccan descent, was one of them. He left his home in the suburb of Schaerbeek, Belgium, for Syria in February 2013, joining Amr’s group. He subsequently returned to Europe several times before building the bombs the Paris attackers used in November 2015, finally detonating himself in Brussels Airport last month.

In all, at least nine of the attackers in Brussels and Paris are known to have spent time in Syria in the years prior to the attacks. Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the Belgian-born mastermind of the Paris attacks, went to Syria in 2013 and became linked with Amr al-Absi, and subsequently to Mehdi Nemmouche, the militant who attacked the Jewish Museum of Belgium in 2014. Nemmouche, while in Syria, tortured the foreign hostages held under Amr’s command.

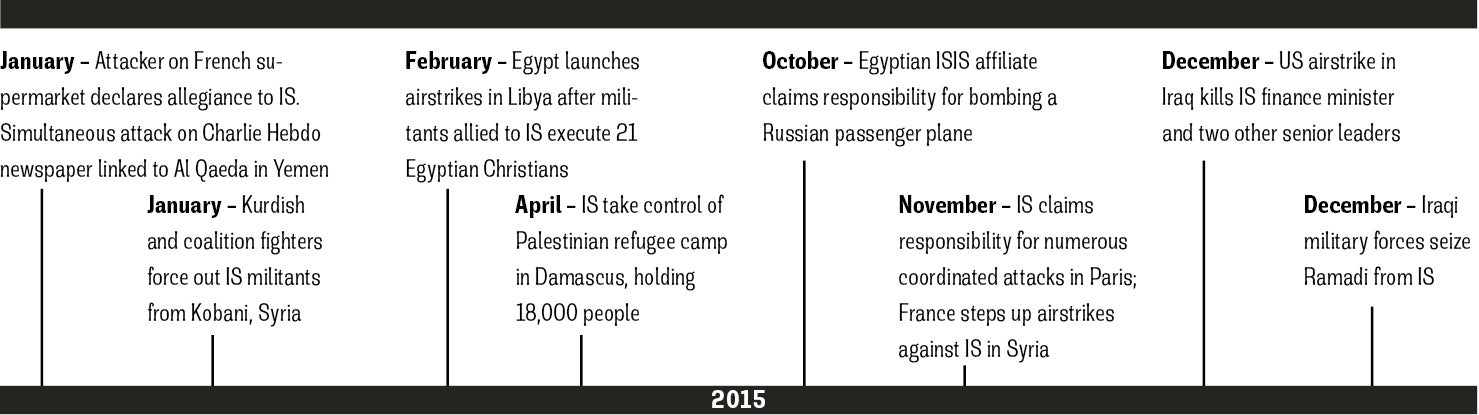

2015 timeline

‘The Chaos’

In early 2014, the Syrian rebels, tired of the group’s brutal and repressive rule, fought back against IS. A bloody battle dubbed the Fitna, or “the Chaos,” saw other rebels take up arms against IS, which was, by this point, operating as an independent entity in Syria.

Zawahiri, al-Qaeda’s leader, soon denounced IS and the groups severed ties entirely. Amr and his men remained loyal to Baghdadi, a move that caused some friction in his ranks but ultimately brought legions of young, foreign fighters who could be manipulated into attacks on western targets.

In June 2014, Baghdadi announced the formation of the caliphate and declared himself its caliph. Then the group pushed into western Iraq. Within weeks, they had forced thousands from their homes and taken huge swathes of territory as the Iraqi security forces melted before their onslaught. At the pleading of the Iraqi government, and concerned about a complete takeover of a country they had previously occupied, the United States began carrying out airstrikes in Iraq.

In the course of the Fitna, Amr and his men abandoned their makeshift Aleppine prison, killing around 300 Syrian prisoners as they departed. Amr told his men to “leave no one alive in the prisons”.

They did, however, keep their precious cargo of foreign hostages, who were moved firstly to a prison outside of Aleppo for safekeeping. They were then handcuffed in pairs and transported on the back of trucks full of dates to a prison outside of Raqqa, a city in eastern Syria that would become the IS capital. “The Beatles” stayed with the hostages.

With Aleppo no longer under IS’ control, Amr was put in charge of media work and installed on the Shura Council, the governing body for the increasingly powerful militant group. This position would give him ample opportunity to wreak havoc in the coming months.

“It was a tribute to Amr al-Absi’s ability as an organiser and negotiator that he was able to at least aspire towards a role as kingmaker;” says Barrett. “The Islamic State leaders saw both the challenge that he might pose if he sided against them and the opportunity he provided if given enough political freedom. By offering him the media role, IS cleverly tied him into its agenda without providing him military resources.”

By the summer of 2014, only the American and British hostages were still in captivity — both countries refused to pay ransoms to the group. In July, US special forces raided a compound in an attempt to rescue the men, but found only DNA samples and empty rooms.

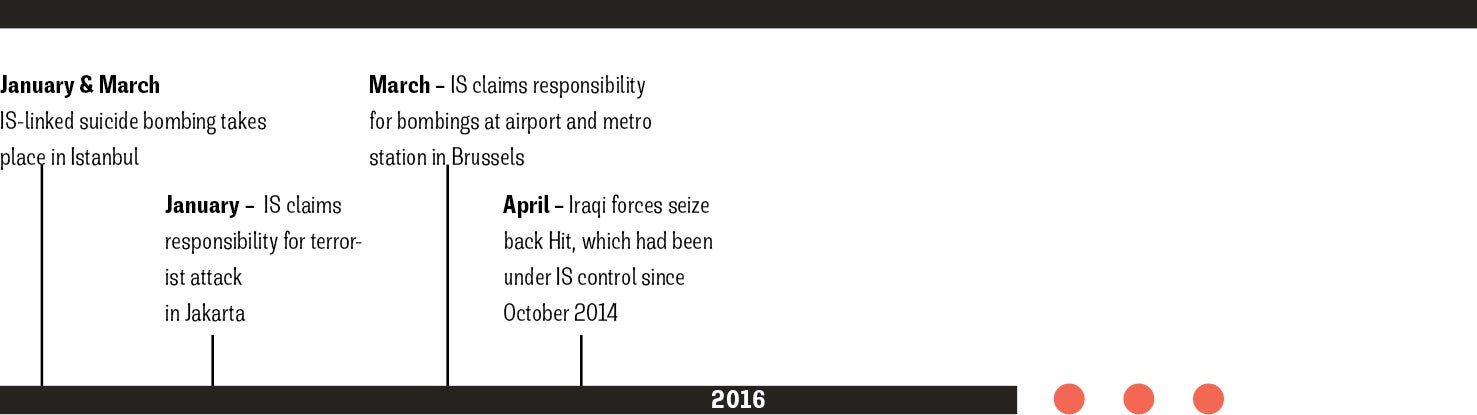

2016 timeline

‘Jihadi John’

Revenge came quickly and brutally. In a perfectly manufactured media campaign, IS beheaded James Foley on video in August 2014. Mohammed Emwazi was the executioner, though he remained masked and unidentified at the time. Amr, in his role as head of media, oversaw the video’s production and release.

For the first time the Syrian Civil War and the goals of IS reached the living rooms of ordinary citizens across the globe. The image of a British jihadist executing an American citizen in the desert in Syria was dripping with symbolism.

President Barack Obama was forced to respond, and respond he did. A fortnight later American reporter Steven Sotloff was executed in a similarly gruesome video and the British aid worker David Haines was threatened. Britain too, reacted by stepping up its military commitment in Iraq.

The search for the identity of “Jihadi John” began; the media and security services became obsessed with identifying the man holding the knife. As three more Western hostages — Haines, Alan Henning, and Peter Kassig — died at his hands before the year was out, his identify remained secret.

Through the winter of 2014 more videos were released: John Cantlie was spared Foley’s fate only to be forced to recite IS propaganda on film; Muath al-Kasasbeh, a Jordanian pilot shot down over Syria, was burned alive in a horrific act of retribution; the Japanese hostages Kenji Goto and Haruna Yukawa were executed in January 2015; and the young American aid worker Kayla Mueller was killed in February.

The image of a British jihadist executing an American citizen in the desert in Syria was dripping with symbolism

All of these videos were released under Amr al-Absi’s direction as head of the media council. Not long after, he was promoted to Emir of Syria, a role which saw him become a more shadowy figure with fewer interactions with outsiders.

The surviving hostages began to release details of their ordeal at the hand of these foreign jihadists and eventually Emwazi was named, his life picked over in detail and his path to radicalisation scrutinised down to the smallest detail. Meanwhile, the Paris and Brussels attacks were being planned. Many of those involved began to travel to and from Syria and Europe undetected, easily evading local security forces. A jihadist named Ride Hame was arrested in France in the summer of 2015 and confessed he was returning to Paris with orders to attack public places and gatherings – Abdelhamid Abaaoud’s name came up often in his interrogation.

On November 12, 2015, the news broke that “Jihadi John” had been killed in a targeted drone strike in Raqqa. British and American politicians and the public were jubilant. The following night, Abaaoud and his accomplices attacked Paris, killing 130 people.

Amr al-Absi was killed in an airstrike in Aleppo on March 3, 2016. He was 36. He had helped create IS in Syria; he had masterminded the kidnapping and public execution of Western hostages, overseen the media strategy that dragged the US and UK into the war, then brought that war to their doorsteps by recruiting and directing the men who attacked Paris. Outside of a few short news reports, though, his death barely registered.

Three weeks later, the remainder of the Paris terror cell he had helped to recruit struck in Brussels. Najim Laachraoui, Amr’s former colleague, was among the bombers, detonating himself at Brussels airport.

By recruiting foreign fighters and showing the world IS’ brutality, Amr wanted to create chaos and deepen divisions within European society. The desperate struggle of security services to close IS’ ratlines to and from Syria, and police raid after police raid in the Muslim quarters of European cities, show how just effective that strategy has been.

Barrett warns that the circumstances on the ground in Syria remain such that others could easily take up Amr al-Absi’s mantle: “Absi lives on an as an example of how individuals can still find opportunity in Syria to build personal power bases and – if they succeed – carve out broader influence.”

Additional reporting by Paul Mutter

Key figures

Amr al-Absi

Born: c.1979, Saudi Arabia

Died: March 2016, Syria

A member of the IS Shura Council of leaders and the mastermind of the group’s campaign of kidnapping and public execution of Westerners, Amr al-Absi was at the heart of a network of foreign recruits, several of whom would go on to commit atrocities in Europe. Saudi-born al-Absi ran the group’s media arm, and was promoted to Emir of Syria before dying in an airstrike in March 2016.

Firas al-Absi

Born: Unknown, Saudi Arabia

Died: August 2012, Syria

The older brother of Amr al-Absi, who would go on to become a senior figure in IS, Firas ran a rebel group in Syria in the early days of the civil war. His extremism led to a split with other, less radical rebels and eventually he was killed in fighting with the Free Syrian Army. His death enraged his brother, who combined Firas’s group with his own, eventually growing it to include many foreign fighters.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi

Born: 1971, Iraq

The leader of the so-called Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi — born Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim al-Badri — remains a remarkably mysterious figure. Believed to have studied theology before founding a militant group in the early 2000s, he rose to become leader of the al-Qaeda affiliate Islamic State of Iraq in 2010. In 2013, ISI split from al-Qaeda and rapidly took over large areas of Iraq and Syria.

Haji Bakr

Born: c.1960, Iraq

Died: January 2014, Syria

Abu Bakr al-Iraqi, or Haji Bakr, was a senior officer in the Iraqi military under Saddam Hussein, but joined the al-Qaeda-led insurgency after the US invasion led to the removal of Ba’ath Party figures from the armed forces. Bakr became military strategist for IS after it split from al-Qaeda, and was reportedly responsible for bloody internal purges in the group. He was killed in a battle with a Syrian rebel group in 2014.

Mohammed Emwazi

Born: 1988, Kuwait

Died: November 2015, Syria

A naturalised British citizen, Mohammed Emwazi joined Amr al-Absi’s fighters in Syria. He appeared in several carefully choreographed and grisly videos where he executed Western hostages, earning the tabloid nickname “Jihadi John”. Once identified, his history sparked a degree of panic in Western capitals, highlighting the threat of domestic radicalisation. He was killed in a drone strike in Raqqa.

Portraits: Matt Ward

ISI Timeline of terror

Raising the flag