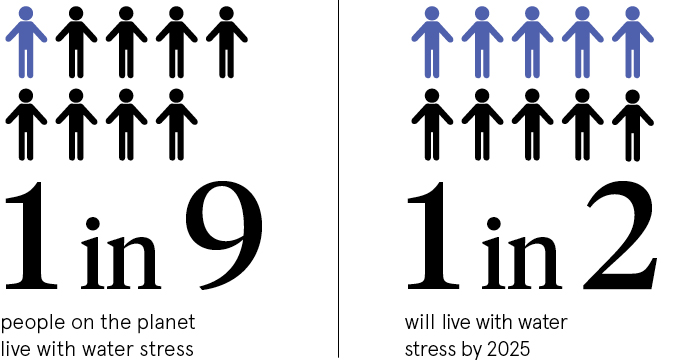

For many, water scarcity is a problem in the post. By 2025, one in every two people on the planet will live with water stress.

For one in nine, the problem is already here. The World Health Organization estimates 844 million people lack basic drinking water; some two billion use a source contaminated with faeces.

International attention has not translated into what is required – thoughtful, sustainable investments

In response, the United Nations made water and sanitation a matter of human rights, declared and defined, in 2010.

Human right to water put centre stage

Justly, if belatedly, the human right to water has therefore been shoved into the spotlight on the global stage. As the climate change drama unfolds, however, gaps between awareness and action persist, says World Resources Institute analyst Samantha Kuzma.

“The UN officially recognises equitable, safe drinking water and affordable sanitation as human rights, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) ambitiously challenge us to provide this right to all,” she says. “Yet international attention has not translated into what is required – thoughtful, sustainable investments.”

Numbers are huge and shortfalls significant. A 2016 World Bank study estimated annual costs of providing water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services to SDG standards could reach $114 billion, three times current investment levels.

Urgency unabated, the UN continues upping the ante, declaring 2018 to 2028 an international decade for action on water.

Boosting human rights requires action not just talk

Making pledges, though, is one thing, delivering on them often another. So, whose responsibility is it to fulfil this promise of the human right to water? Does it fall to governments, the private sector or maybe transnational partnerships?

Water is a team game, albeit a political one, says Ms Kuzma. “The first step is establishing political will to make change happen,” she says. “Pressure must come from all – investors and financial institutions, diplomats, private companies, and citizens – both impacted and not.”

Big as the challenge may seem, success can be bigger. Following devastating famine in the 1980s, the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia invested heavily in grey and green infrastructure to provide almost 30,000 people with clean water. Irrigated land now totals one thousand times the area in the mid-1990s and Tigray, once the poorest region of Ethiopia, has been self-sufficient in food production since 2007.

Rwanda is in turnaround too, transformed since the dark days of brutal civil war. Now almost three in five people have clean water and two thirds of the population a decent toilet.

Two threats to water access: infrastructure and resources

Essentially, water challenges fall into two categories, explains Richard Munang, Africa regional climate change co-ordinator with the United Nations Environment Programme. “First are water infrastructure challenges, where the key issue is an inability to harness and distribute water from its sources,” says Dr Munang. “Second are water resource problems, where dwindling surface and subsurface sources are the issue. From the climate change perspective, our main focus is on water resource trends, especially in Africa.”

With a warming of 2 to 4C, the region will experience 60 to 80 per cent reduction of surface run-off by 2100 and groundwater recharge rates down between 30 and 70 per cent.

While policy might be the biggest driver of change, it is more a question of implementation and a joined-up holistic approach than new frameworks, argues Dr Munang. “Water policies need to reconcile and be implemented in synchrony with environment and forestry policies to ensure these ministries align their resources – financial, technical and technological – in restoring water-catchment sites,” he says.

Human rights issues around water are by no means confined to rural communities, however.

At 55 per cent already, the proportion of the world’s population living in urban areas is forecast to hit 68 per cent by 2050. Building urban water resilience is therefore key, says Mark Fletcher, global water leader at Arup.

“Many cities and towns are in low-lying coastal locations, so flooding and loss or deterioration of water supply is a direct threat to human life, as well as the economic, social and environmental life of these communities,” he says. “Local authorities need to safeguard their citizens from climate-related risks, arising from either too much, too little or contaminated water.”

Conflict is also a threat to the human right to water

When it comes to water, not all threats to human rights are climate related; conflict is another critical factor.

In eastern Ukraine, shelling and gunfire is a daily reality, with conflict ongoing since 2014. Along the 500km frontline runs critical water infrastructure, which is regularly hit and damaged, affecting supply on both sides.

Campaigning under the banner of Protect Water Ukraine, Czech-based NGO People in Need (PIN) is working there with transnational partners to protect this infrastructure and help alleviate the suffering of civilians, ensuring vital supplies to schools, kindergardens and hospitals.

The initiative forms part of WASH efforts supported by the UK Department for International Development, European Commission’s Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations and Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Ania Okinczyc, country director for PIN in Ukraine, outlines the scale of the challenge: “Last year, on average, water infrastructure along the frontline was damaged every three days, with some 135 incidents in 2017 alone. This year, over four million people are at risk from outages and loss of supply.”

To make matters worse, Ukraine’s centralised heating systems need water to operate. So, as temperatures drop below zero this winter, hundreds of thousands of people will struggle to keep warm.

With fighting parties unable to agree a ceasefire, however, fixing damaged water pipes, filtration and pumping systems is not just a matter of engineering, but civilian protection too, concludes Ms Okinczyc. She says: “Since 2014, twenty-five water workers have been injured and nine killed trying to make vital frontline repairs.”

From climate to conflict, Ethiopia to Ukraine, the problem of water is simultaneously global, yet local, and the solution the same. Responsibility is shared, risk is not. However, were water to become the next big human rights success story, that is something we could all drink to, literally.