If you’ve watched a sci-fi movie in the last 30 years, you’ll know what the future of money is – because no one ever pays for anything. From Arnold Schwarzenegger’s cab ride in Total Recall to Luke Skywalker getting a drink at a scary spaceport bar, nary a shekel changes hands. Which isn’t, it turns out, lazy scriptwriting – it really is the future of seamless payments.

Obsessed with removing the distressing, time-consuming and purchase-squashing horror of pulling a £10 note from your pocket, a host of digital startups, tech labs and major banks are looking to revolutionise every aspect of anteing up. They are turning to biometrics, data, artificial intelligence (AI) and even bio-implants to ensure you can leave your house, step into a driverless taxi and grab breakfast from your usual coffee shop without even thinking about payments. Indeed, the main reason for interacting with the smartphone or wearable banking app will be to manage your personal portfolio.

So dramatic are the anticipated changes that Francisco Gonzales, chief executive of Spanish banking giant BBVA, predicts the next 20 years will see an entirely new financial ecosystem being created, going from 20,000 analogue banks today worldwide to no more than several dozen digital banks. He predicts that diverse niche businesses will exist, but will be tied into the digital banks for the so-called banking rails that underpin transactions.

Predictions versus reality

Of course, nothing is as simple as this. For a start, cash is stubborn. The working man’s tax haven, hard to track and easy to spend, is outperforming predictions of its demise. In 2015 it was still the most popular form of payment, accounting for 48 per cent of all transactions, compared with 24 per cent for debit cards and 10 per cent for direct debit. 2015 was, however, the first year cash slipped below 50 per cent of all transactions. With just 34 per cent of payments expected to be cash by 2024, what will take its place?

Jesse McWaters, project lead of disruptive innovation in financial services at the World Economic Forum, predicts three key systemic changes: the triumph of the “default card”, the card that consumers use in online and mobile payments; expecting this to be a debit card, he predicts the death of the credit card; and he expects digital currency systems to modernise the payments infrastructure.

What this doesn’t account for is the surge in innovation in financial technology (fintech), with challenger banks and new service providers hoping to use predictive technology and AI to overhaul lending, and introduce sweeping changes.

“The biggest change we’ve seen recently is that for the first time in 350 years, banks are interested in their customers’ experience – customers used to have to go to the bank, now the bank has to come to them,” explains Phil Cantor, iGTB’s head of digital. “In time, technology will help restructure the way banks work with customers completely. Right now, if I need a loan to pay an overseas supplier, that’s at least two departments at my bank. What customers need is a bank that can keep them liquid so they can order money into an account when they need it and pay it back when they have it.”

Mr Cantor points to Square, the payments platform now offering loans to its merchants without them even requesting one, basing the loan offering on the transaction volume it sees the merchant processing and repayment directly out of the transaction stream.

Taking lending a step further

Moving corporate banking closer to this fluid lending, iGTB recently launched sanctions screening, an AI which offers a natural-language contextual search of social media to identify high-risk clients, along with a wearables extension of its corporate banking digital enterprise platform CBX, offering the complete spectrum of transaction banking and aimed initially at the Apple Watch.

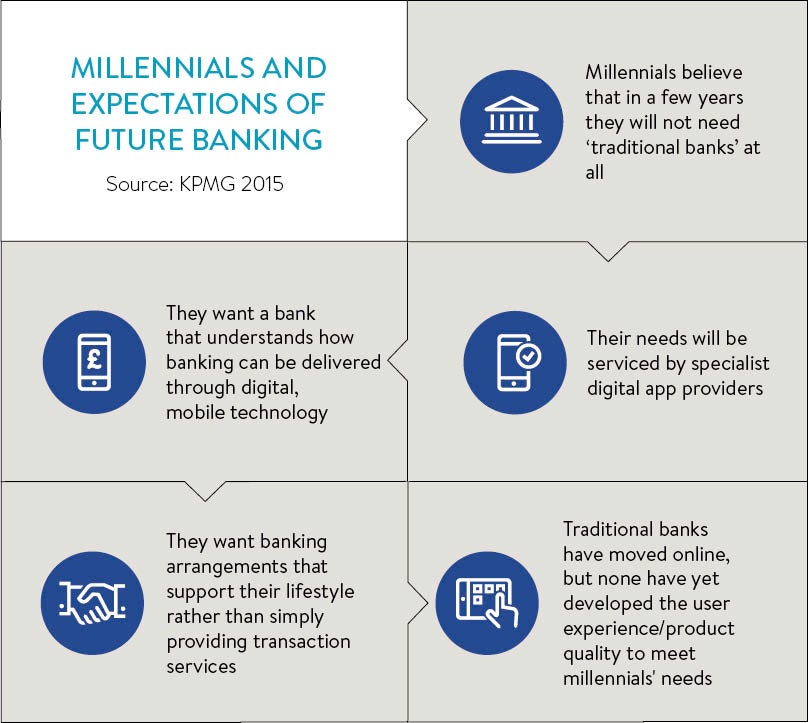

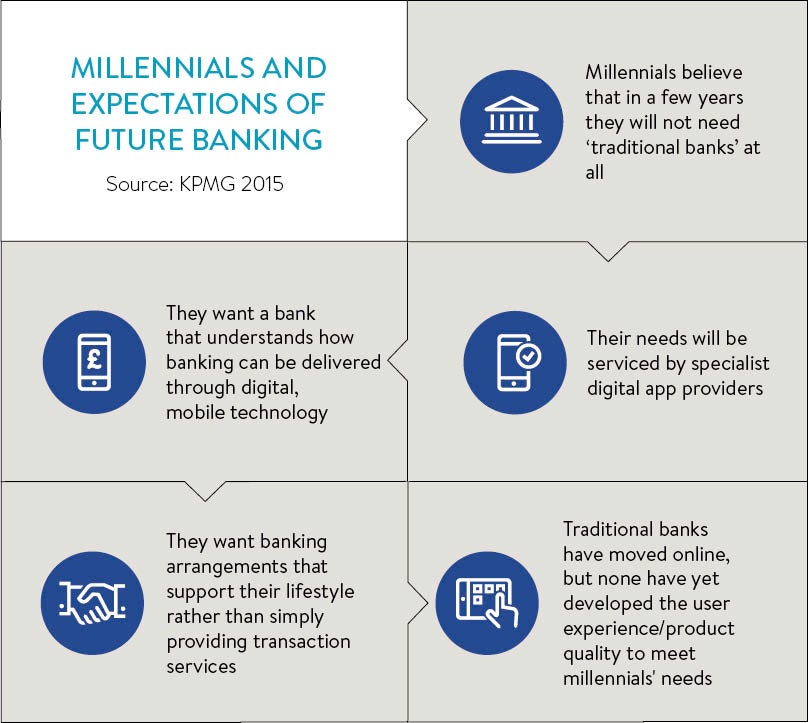

This kind of broad interface offers trusted banks a chance to move from traditional bank to bona fide consumer brands, argues Andy Masters, head of savings and wealth at KPMG. In the short term he envisages a near future where mainstream financial services brands such as Barclays would use technology that already exists to bring together all their pension, savings, borrowing and cash account values from any provider on the same smartphone app. Slightly further out, he predicts machine-driven financial planning advice, which will view assets and liabilities, understand a customer’s risk attitude, and recommend strategies in real time and prompt customer action.

“There are data privacy concerns, of course, but if you’d suggested ten years ago that private companies would issue people with a device that measures their health on a minute-by-minute basis, there would have been a big brother outcry,” says Mr Masters. “Then along came the likes of Fitbit. It needs an under-the-radar approach like the Fitbit, but banks could become the mobile equivalent of the old AOL home pages.”

[embed_related]

Barclays bPay wristbands and its imitators are hoping to become the Fitbit of money, taking advantage of contactless to conduct small transactions without needing a wallet. Taking contactless far afield, Paul Makin, head of digital financial services and financial inclusion at Consult Hyperion, shows how mobile and contactless can work even in the difficult environment of a refugee camp.

Consult Hyperion is working with the Department for International Development on payments for refugees in Syria. Charity field workers carry toughened Android tablets that sync with credit card-sized payment cards on to which charities can send weekly payments – payments that used to be made in bundles of cash carried around war zones in vulnerable trucks. In a wi-fi area these tablets upload and download information so that, when taken into an unconnected camp, cards can be topped up and spending recorded. The charity can then reimburse merchants.

Biometrics making payment possible anywhere

“Financial futures really are about financial inclusion or they won’t work,” Mr Makin argues. “Right now, for instance, Apple is leading the charge on biometrics with its fingerprint lock on the iPhone. Actually fingerprints are only really useful for young office workers. If you’re a manual worker, if you’re really dehydrated, if you smoke or if you’re over 50, fingerprints are far less reliable.”

Ian Pearson, futurologist at forecasting consultancy Futurizon, suggests fingerprints with 64-bit codes imprinted may help. He’s also keen on gesture recognition or heartbeat monitoring. “It needs to be fluid and unfakeable, which is tricky to guarantee,” he says.

The blockchain is essentially a huge multi-user digital ledger that, at the moment, can’t be erased or altered and records every transaction permanently

One solution, Mr Pearson suggests, is quantum money, using bleeding-edge quantum computers to issue currency that can’t be copied, which would make it possible for any of us to create our own payment system, using anything from time to bandwidth to supply value. There’s also the much misunderstood blockchain – the technology behind the infamous Bitcoin – which many see as the future of both payments and identity.

The blockchain is essentially a huge multi-user digital ledger that, at the moment, can’t be erased or altered and records every transaction permanently. Many banks, including BNY Mellon, are exploring ways in which the properties of the blockchain can be leveraged, explains Dominic Broom, BNY Mellon’s head of treasury services in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “The blockchain concept can be applied to any digital asset, such as security, bonds, loans and collateral, and could therefore be used in a number of different areas,” he argues.

Brian Forde, MIT Media Lab director of digital currency, goes further, predicting a new capitalist revolution. “Cryptocurrencies and blockchain are the open protocol of payments, the SMTP [simple mail transfer protocol] of money,” he says. “People talk about Uber and Airbnb as disruptive, but they’re intermediaries just like the incumbents. The blockchain actually disrupts the disruptors.

“Capitalism took off in countries such as the US with most small-business owners borrowing against their home. Where people don’t have a formal property title, like in Egypt, all this capital is tied up. If you have a property title put on the blockchain, even if there is then a government that no longer respects the title, it’s on the blockchain – the government can’t say you never owned it. In Egypt, that unlocks $400 million in capital.”

Which may sound a little bit like science fiction, but at least it suggests there’s someone paying for something.

CHALLENGER BANKS

Francisco Gonzales, chief executive of Spanish banking giant BBVA, may be predicting that 20,000 old-school banks will dwindle to several dozen digital banks in the next 20 years, but the evidence from the burgeoning challenger bank scene suggests otherwise.

Francisco Gonzales, chief executive of Spanish banking giant BBVA, may be predicting that 20,000 old-school banks will dwindle to several dozen digital banks in the next 20 years, but the evidence from the burgeoning challenger bank scene suggests otherwise.

Born out of the financial crisis of almost ten years ago, challenger banks range from the relatively traditional Virgin Money, which purchased Northern Rock’s viable assets, to punchy startups such as Tandem, the UK’s first mainly mobile bank. Although undermined by recent reports that five of the biggest of the roughly 40 challengers were being run by former Royal Bank of Scotland executives, business has boomed. Aldermore and Shawbrook Bank have lent more than £10 billion combined, and both have floated successfully.

Many are primarily lending vehicles. Shawbrook and Aldermore are specialist savings and lending banks, though some, such as Metro Bank and OakNorth Bank offer high street checking accounts. And it’s not just UK-based banks that Brits are choosing. Berlin-based Number26 is a Europewide mobile-only full service bank, with a huge reach among UK millennials.

“Normally you have to sign up to a bank account on paper – with ours you can do it on a mobile phone in around four minutes,” explains co-founder Valentin Stalf. “Our customers log in to our app at least every two days so we can constantly react to what customers need.”

OakNorth’s chief executive Rishi Khosla isn’t sure technology is crucial to good challenger banks and pitches human contact over the algorithm. “We always make sure a real person decides on any loan taking all factors into consideration,” he says. OakNorth’s lending is largely to smaller businesses, a sector that has struggled to get loans from established banks since the 2008 crash.

The drop in lending by UK banks and building societies has prompted the growth of crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending, with almost $80 billion raised worldwide, according to data from industry watchers Preqin. The sums are still relatively small in the UK; one survey by online marketplace Funding Options found that just 18 per cent of loans to UK small businesses were supplied by crowdfunding, peer-to-peer lending and rich individuals.

“Peer-to-peer lending is looking increasingly like a bubble – there are some 1,800 platforms around the world,” warns Kamel Alzarka, chairman of the insurgent Falcon Group, which lends to mid-cap companies, a sector that has struggled with banking support. “At the same time banks are lending less – challengers will only grow.”

Predictions versus reality