At the tender age of 87, Michelangelo said “I am still learning”, making him a poster child for lifelong education.

Learning has come a long way since Renaissance Italy, but educators and administrators still face the same concerns in equipping students from school to university for the world of work; except today’s world is faster and more automated, with flexible patterns of employment.

Joe Fuller, a Harvard Business School professor who co-leads the school’s initiative Managing the Future of Work, explains that future employment is going to be much more variegated than it is today. “People will have lots of different types of working relationships,” he says. “Most companies today are made up of full-time and part-time employees. Expect to see a significant increase in gig workers.”

Survey highlights need for curriculum shake-up

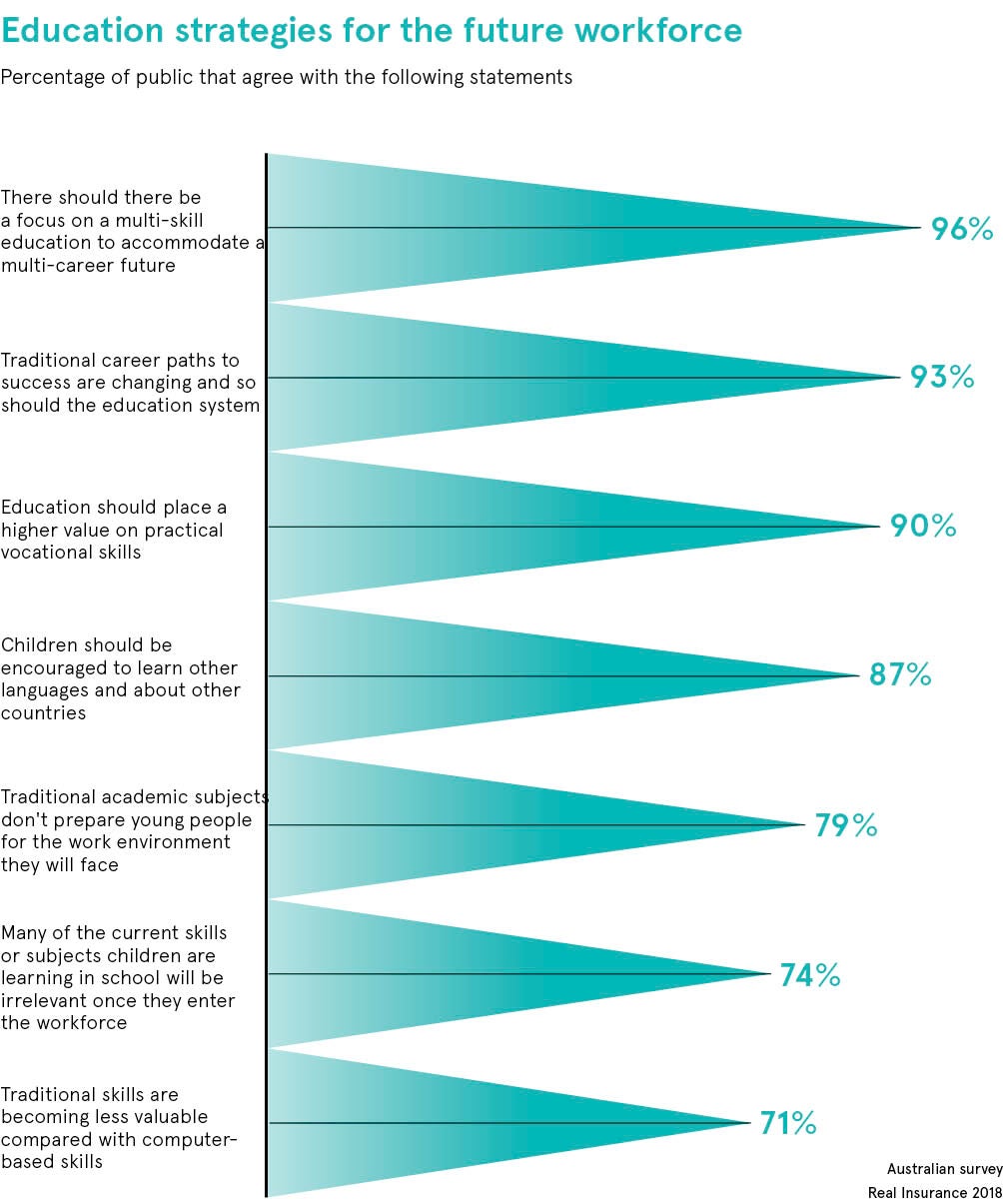

Many education stakeholders are calling for a shake-up of organisation and curriculum to meet 21st-century needs. In a recent Australian Future of Education survey, undertaken by Real Insurance, 42 per cent of respondents said the current school curriculum is inadequate, 23.2 per cent said basic literacy is lacking and 30 per cent are not confident children are being prepared for future jobs.

It’s about blending technology with the right curriculum design

The survey concluded that few Australian parents are confident in the school curriculum and worry about how well the education system aligns with the needs of future workplaces.

Those surveyed also indicated discomfort with the adoption of virtual classes or teachers. Garry Falloon, professor of digital learning at Sydney’s Macquarie University, says fears of technology taking over classrooms and the increasing role of tech in the workplace highlights the importance of balance. “It’s not an either-or scenario,” he says. “It’s about blending technology with the right curriculum design.”

Education is slow on the technological uptake

It is also about place. Classrooms today look very similar to the classrooms pupils’ parents learnt in, but with some new tech added. Joe Williams, executive director of America’s Democrats for Education Reform, says: “With some exciting exceptions, public [state] schools are one of the few institutions in modern life that have not seen radical changes spurred by technology.”

Yet, educators are expected to teach skills and problem-solving for jobs that don’t exist for 65 per cent of the children starting school this month when they come to seek employment. As times change and market needs evolve, educational subjects come in and out of vogue, while others are threatened with abandonment. Classics is a good example, though Jeremias Prassl, associate professor in the Faculty of Law at Oxford University and author of Humans as a Service, reminds us: “Latin is useful, it is a language. Computer programming is also a language.”

There are fears and opportunities to be explored, says Professor Prassl. “It’s not just the negative of losing jobs. The history of work tells us technology makes work more interesting, more productive. It’s not just the destruction and substitution of jobs, but the creation of new types of jobs. It’s a question of agency. The future of work is not something that happens to us; we have a say in this, whether it is as individuals or through the agency of groups,” he says.

Educators must be flexible and future-focussed

Professor Prassl, whose book examines work in the gig economy, warns of the innovation paradox, in that while innovation in the gig economy is reliant on modern technology, as far as work is concerned, it also uses a business model that is ancient.

He explains: “We need to be quite careful not to confuse the positives of technology with technological exceptionalism. Is it actually true we need separate skills? Many tasks will be automated; we need to understand the processes, how they work.” This understanding seems to be accepted in many countries.

In Singapore Ng Chee Meng, minister in the prime minister’s office and, until recently, the minister of education for schools, stresses the need for “21st-century competencies such as critical and inventive thinking, and soft skills such as communication and cultural awareness”.

Educators in New Zealand are promoting what they call the future-focused principle and the need for educators to be future-oriented and adaptable. Dr David Parsons, associate professor at Massey University in Palmerston North, explains in a New Zealand Ministry of Education presentation: “The curriculum encourages students to look to the future by exploring such significant future-focused issues as sustainability, citizenship, enterprise and globalisation.”

Essential skills will still need a human to teach them

Sarah Weir, chief executive at the UK’s Design Council, questions who will build the human connections that are at the core of such skill areas: “Can robots teach collaboration, creativity and disruptive thinking? I don’t think so.”

She adds: “Imagine a school class with children fully engaged and immersed in working together to solve real-world issues. They are self-driven, collaborative, coming up with new ideas and throwing out the ones that don’t work. They think creatively and apply this across their entire life. Surely it’s important for our young people to have the skills they need to design their future, drive the economy and solve the global challenges they face in the future?”

Professor Prassl believes forecasting underlying skills is not necessarily a new challenge. In his own discipline of law, he says: “The law always changes and as legal educators we need to focus on transferable skills, such as legal thinking and writing. We need to focus not just on the content, but how we go about teaching it. Do you emphasise the passing on of knowledge or the critical interrogation of the subject? One of the joys of education is that it is never static.”

Survey highlights need for curriculum shake-up

Education is slow on the technological uptake

Educators must be flexible and future-focussed