Urbanisation is a monster. According to United Nations data, the proportion of the 2014 world population living in urban areas was 54 per cent, heading for 66 per cent by 2050.

Urbanisation is also greedy and dirty. Inhabitants consume 75 per cent of the planet’s natural resources and contribute to urban activities responsible for 75 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions.

The numbers are sobering. It is easy to see why technological innovations that promise resource efficiency and mobility would be attractive to city planners, architects and engineers.

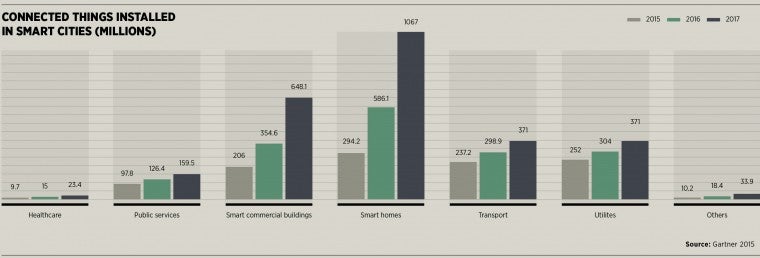

Given the scale of the problem, it is no surprise then that the size of the prize for solutions is equally large. Forecasts from Frost & Sullivan suggest the global smart city market will be valued at $1.565 trillion in 2020. Some 1.1 billion connected things are now in use in smart cities, according to Gartner research, rising to an estimated 9.7 billion by 2020.

Public and private money is also already on trend. In the European Union, the Smart Cities and Communities European Innovation Partnership has been backed by €365 million of European Commission funding. In the UK, the 2015 Budget saw chancellor George Osborne allocate £40 million for the internet of things (IoT) in healthcare, social care and smart cities.

Such sums, however, look pretty modest viewed alongside the investment plans of Cisco, for example, which originally set aside $100 million just for “internet of everything” (IoE) startup companies and has followed this up with a further $150 million as part of a $2-billion portfolio in disruptive technology markets.

Cisco has identified six particular cities spearheading the technological leap forward – Barcelona, Bengaluru, Chicago, Hamburg, Nice, San Jose and Songdo, South Korea. It has collaborated to develop Asia’s first end-to-end innovation hub in Bengaluru, India. Its E-City Living Lab is home to a cluster of more than 185 companies and emblematic of the company’s investment focus in the country. With India’s prime minister Narendra Modi’s plan to roll out 100 smart cities, Machina Research forecasts India will account for $10-12 billion of the global IoT market by 2020.

All this talk of potential and market speculation sounds exciting, but what is actually happening on the ground?

There are new-build one-offs of note, such as Abu Dhabi’s Masdar or Fujisawa, the Panasonic-led smart town in Japan. Otherwise, in established cities, perhaps not as much radical innovation is in evidence as you might expect, argues Andrew Comer, cities director at Buro Happold Engineering.

“There are many cities thinking about opportunities for technology to improve operations and services, but not many really want to be used as a laboratory with the risk of failure. Physical examples are currently limited to incremental advances in areas such as smart grids and networks,” he says. With the possible exception of cities such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Copenhagen, Mr Comer sees a cautious and conservative mindset at work.

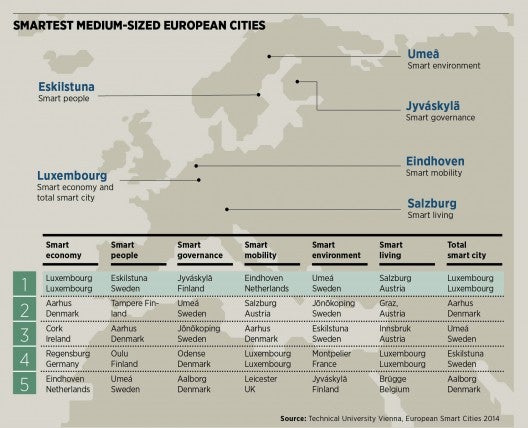

[infographic]

For Charbel Aoun, senior vice president for smart cities at Schneider Electric, however, the catalytic power of the IoT for smart cities actually lies in the multiplier effect of its somewhat utilitarian functionality. “IoT simplifies smart cities. Cities already understand the process of sensing and actuating to collect and act on data. IoT has been happening for years with traffic light systems, automatic number plate recognition and the like, it’s just increasing scale and reach,” he says.

Mr Aoun can reel off a range of apparently unremarkable applications for the IoT: streetlights that can sense and adjust to the environment and conditions, whether people or traffic are passing, or notifying if a bulb fails; monitors for water leaks, with the facility to shut off pipes automatically; or simply sensors to detect full rubbish bins.

In reality, resource management issues in energy, water and waste are being tackled in a myriad of small ways, one sensor at a time, with a trillion sensors forecast worldwide for 2030 – more than 100 for every human on Earth.

[embed_related]

The effect is both cumulative and potentially transformative, says Mr Comer. “As technology becomes embedded within more and more everyday objects, and parts of objects, so the dynamics of city systems and city lifestyles will change from one of a layered and linear set of data collection, analysis and reaction, to real-time interchange of sensing and response across a very broad spectrum of city operations and activities,” he says.

Joined-up sensing calls form a bedrock of commonality, says Bilel Jamoussi, study groups department chief at the Telecommunication Standardization Bureau, International Telecommunication Union (ITU). “The internet of things involves the interlinking of networks, devices and data that have thus far never been linked,” says Dr Jamoussi. “It is the collective power of these utterly disparate elements that lies at the heart of the power of IoT and the smart city. International standardisation through public-private co-operation is therefore indispensable to ensure things, devices and processes speak the same language.”

In response, ITU members have established a new study group to address standardisation requirements, with an initial focus on the IoT in smart cities. Singapore offered to host the inaugural meeting and, in May, Dubai became the world’s first city to assess efficiency and sustainability of operations.

The internet of things in smart cities is more a matter of the unseen, unheard creep of covert data collection and real-time response, sneaking up on society

In the UK, backed by the government’s Innovate UK programme, the HyperCatCity initiative also looks to use an open and interoperable standard to do away with conflicting systems. The London DataStore official free-access site for the Greater London Authority has “HyperCat-enabled” its data, making it possible for anyone to build applications from it. Pilot programmes are also in place for Milton Keynes and Bristol.

Working towards what the ITU dubs “systems of systems”, it might be easy though to lose sight of cities as places for people. Some of the indirect effects of the IoT in cities will revolve around collaborative behaviours among humans, not just things, says Léan Doody, smart cities lead at Arup Digital. She says: “IoT will allow us to connect people, things and places in new ways. This will allow us to build new services combining things and locations to allow for a more responsive city experience – and potentially share resources better than we do now.”

We are already seeing ride-sharing, bike hire and electric vehicle rental, for example, being enabled by mobile and digital technology, and having a growing impact on reducing the need for land given over to city-centre parking. IoT-enabled co-ordination with public transport provision and access also serves to ease congestion, reduce pollution and increase mobility. Smart cities are where the sharing economy meets the digital and physical world, simultaneously and sustainably.

In terms of the planning and design of the built environment and physical infrastructure, will IoT-enabled smart cities actually start to look different though? According to Ms Doody, there are some signs of change, but again they are slight and slow. “We are beginning to see examples of how technology is changing use of physical space – for instance, with the implementation of Oyster [travelcard] and contactless payment, we don’t need ticket offices.”

Such transformations are hardly dramatic, however, leading Mr Comer to predict that future smart cities will actually look very similar in fabric terms, but very different in the way we interact. The truth is, at present, the IoT in smart cities is not all artificial intelligence, robots and driverless cars. It is more a matter of the unseen, unheard creep of covert data collection and real-time response, sneaking up on society, app by app.

PALO ALTO: CALIFORNIA DRIVIN’

Home to Hewlett Packard and Tesla Motors, next door to Stanford University and down the road from Apple and Google, the city of Palo Alto is located in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Also newly opened in the California city is the Research & Innovation Center of the Ford Motor Company, leading the vehicle manufacturer’s work on driverless cars, connecting autonomous vehicles to smart homes and the Nest thermostat.

Not surprisingly, then, given its proximity to such world-leading technology providers, the city of Palo Alto is also now equipped with one of the first traffic management systems in the United States to address the IoT driving connected vehicle initiative.

The ATMS 2.0 system from Trafficware incorporates SynchroGreen, which will update signal timings in real time based on current traffic demand, and help alleviate congestion and reduce delays. A web-based driver information system allows the public to view real-time traffic conditions, video feeds and obtain current traffic data using a web browser, smartphone or tablet. The system will integrate with the city’s future parking management system and includes real-time occupancy data in downtown Palo Alto.

“As we looked for a partner for traffic management for the next decade, it became important to consider capabilities for connected vehicles,” says Jaime Rodriguez, Palo Alto’s chief transportation official at the time the initiative was announced.

“The city is expanding functionality of the traffic management system to meet the data-sharing demands that we anticipate within our market. Trafficware has demonstrated the ability to provide data to smart vehicles through previous projects with European automobile companies. It is the city’s intent to build on these partnerships and data-sharing capabilities to make automobiles more fuel efficient and empower motorists in Palo Alto with more information.”

Connected services typically include safety information with severe weather warnings and alerts about road conditions, plus entertainment features, such as music-streaming and social media networking.

According to Business Insider Intelligence, by 2020 some 75 per cent of all cars worldwide will be equipped with internet access and associated software, with global revenues from connected services expected to top $152 billion.

Research by KPMG has forecast full highway pilot features by 2017, with vehicle autonomy from 2025. It estimates connected and autonomous vehicles could provide a £51-billion boost to the UK economy and reduce serious road traffic accidents by more than 25,000 a year by 2030.

A QUESTION OF SMART CITIES

Q&A Dr Andy Stanford-Clark, master inventor and engineer at IBM, gives Jim McClelland his assessment of the impact of the internet of things on smart cities

Q. As the smart city phenomenon spreads around the world, how important will it be for cities to collaborate in sharing knowledge and best practice if the global community is to get smarter, faster?

A. Something that has become very apparent is that smart cities are an ecosystem of parts played by many different actors. No one company can do the whole thing, and it really is a case where organisations need to focus on delivering their core competencies and collaborate across well-defined interfaces with many other players. When this happens a “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” effect happens and a smart city emerges.

Q. In what ways does the internet of things (IoT) change the game for smart cities?

A. The IoT is all about getting valuable insight from real-world data. Whether it’s a little plastic bus on your mantelpiece that flashes red when the real bus is five minutes from the bus-stop near your house, or it’s better traffic flow round the city thanks to active monitoring of queues and management of traffic-light sequencing – sensors out in the streets are sending data back for real-time analysis to provide better services for the citizens.

Q. What might be an example of basic IoT application in smart cities?

A. An example might be connected vehicles sending operational data back to manufacturers for predictive maintenance, or sending location, speed and destination data to the traffic planning systems to enable traffic flow through the city to be optimised, or sending information about traffic jams and collisions back along the line of cars to enable safer braking and possible diversion planning.

Q. What might be an example of really radical or ambitious IoT?

A. Radical or ambitious would be full integration of transport, electricity, healthcare, education, city services, water, heating, work and leisure activities within a co-ordinated framework, fully interlinked and achieving a “whole is much greater than the sum of its parts” effect. IoT enables a jigsaw of pieces to fit together into a complete picture.

Q. How much of a concern is data security with IoT in smart cities?

A. Security is a concern, certainly, but there are perfectly good mechanisms that we use, such as secure connections to online shops, which can be used for securing the IoT. It should be designed-in from the beginning rather than retrofitted. There has to be more effort made by the organisations who use our data to educate us about exactly what they will use it for and what the benefits to us will be in return for giving up that data. A good example would be supermarket loyalty cards that clearly use the “give-to-get” model with their customers. More generally, organisations have to understand not just their legal, but their moral obligations too and not ask us to give up control of our data through the small-print in their terms and conditions of use.

Q. If you were to close your eyes and dream, what could an IoT-enabled smart city look like in five years?

A. The vision I dream about in five years’ time is one in which transport is fully integrated. So when I set off from my home to work, live tracking data, merged with timetable information, will suggest an optimal route, which may change during the journey. Say the bus is delayed in traffic so I miss the train, I’d like get a text to tell me to get a different train from a different platform and then make one extra change to get to work just ten minutes later than planned. At IBM, we’re working on that integration in cities such as Southampton and Dublin – and the Isle of Wight ferries already tweet about their arrival and departures from the ports.

PALO ALTO: CALIFORNIA DRIVIN’