Your car can sit outside your home for days doing nothing. Research from the RAC Foundation shows the average car spends about 80 per cent of the time parked at home, 16 per cent parked at work and it is only in use about 4 per cent of the time.

Is it any surprise many are looking at alternatives and see little benefit in car ownership?

In London, the transport authority says the reasons people chose not to own a car are cost, stress, car parking, congestion and good availability of public transport.

The reasons people chose not to own a car are cost, stress, car parking, congestion and good availability of public transport

And research for University College London shows car use peaked at 50 per cent of all trips in 1990 in the capital and has now fallen to 37 per cent. It is predicted to fall further.

Evolving cities

Car ownership for some in cities is no longer a freedom; it’s an expensive hassle and local public policy is playing a part in that. In central London, there is already a £10 congestion charge. There could also be a £12.50 “toxic” pollution charge for cars built before 2005. And the cost of car parking can be £4.90 an hour in Westminster; that’s if you can find a space.

Cities are changing. There are “public realm schemes” introduced to improve the environment for cycling and walking. The flipside of that is driving in some areas takes longer.

Take the Torrington Place area of Camden in London. Road space has been taken away from vehicles and given to pedestrians and cyclists. There are plans for key routes in the capital like Tottenham Court Road to be bus and bike only during the week. Oxford Street, a main shopping area, will also be pedestrianised.

Will London follow in the steps of Paris and Oslo?

And there has also been investment in segregated bike tracks to try and encourage modal shift away from cars. The latest figures from Transport for London show the number of car drivers entering the centre in rush hour fell from 137,000 in 2000 to 64,000 in 2014. The number of cyclists trebled from 12,000 to 36,000 over the same period.

Transport bosses say the shift away from private cars to public transport, walking and cycling is “a feat unprecedented in any major city”.

These changes aren’t welcomed by many drivers, especially the vocal black cab lobby, but this policy shift isn’t just restricted to London.

In Oslo cars will be banned from the centre by 2019 to reduce pollution. Large areas along the River Seine in Paris will be pedestrianised this summer as the city tries to clean up its air. In Dublin there are plans for key sections of the city centre to have no vehicles at all by 2017.

Apps and car clubs

On top of public policy, you can add the new instant interactivity and practicality of the smartphone and ride-sharing and hailing apps. It’s common to see someone tapping on a phone, standing on a street corner and either a black cab or a minicab pulls up.

You can use your smartphone to locate anything from black cabs, buses, hire bikes, car clubs and shared rides.

If you have a postcode you can enter it into an app and it will plot the quickest way there using public transport.

Our goal is a future where car-sharing outnumbers car ownership

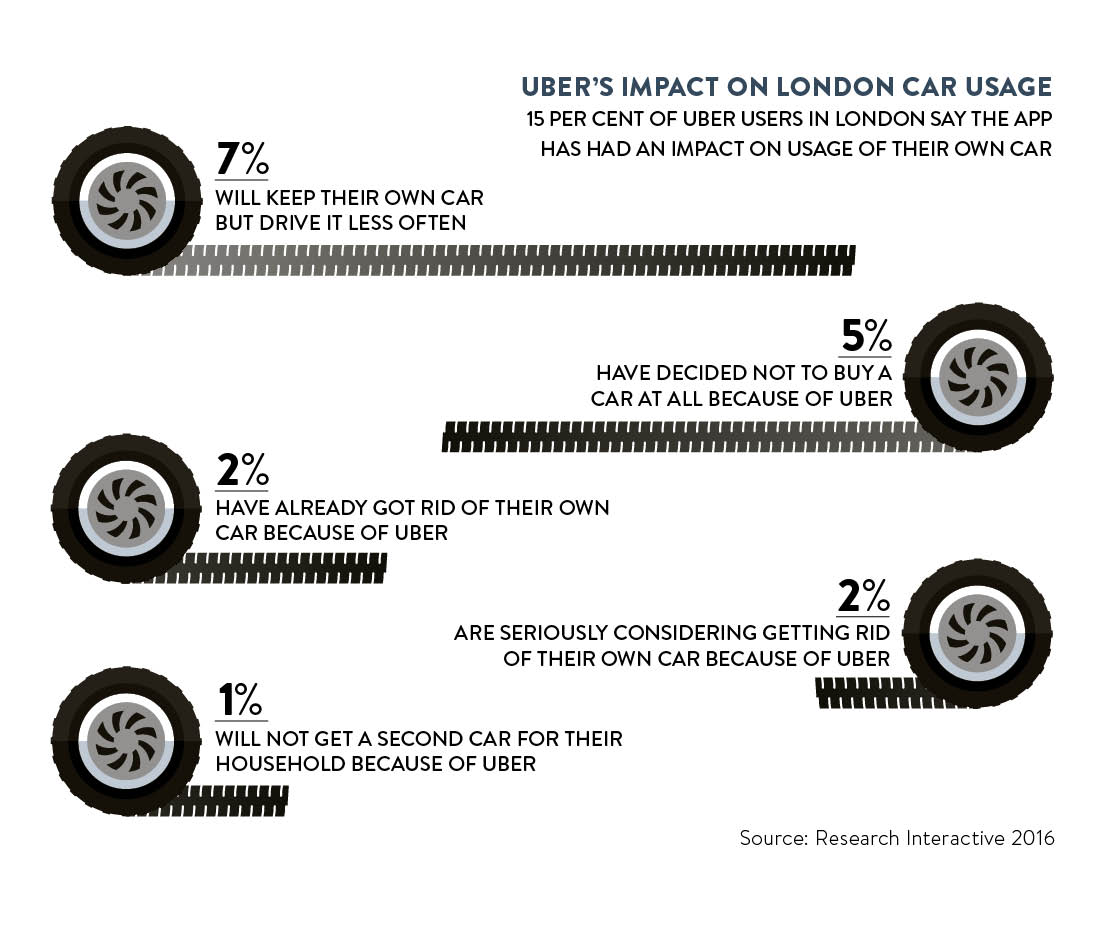

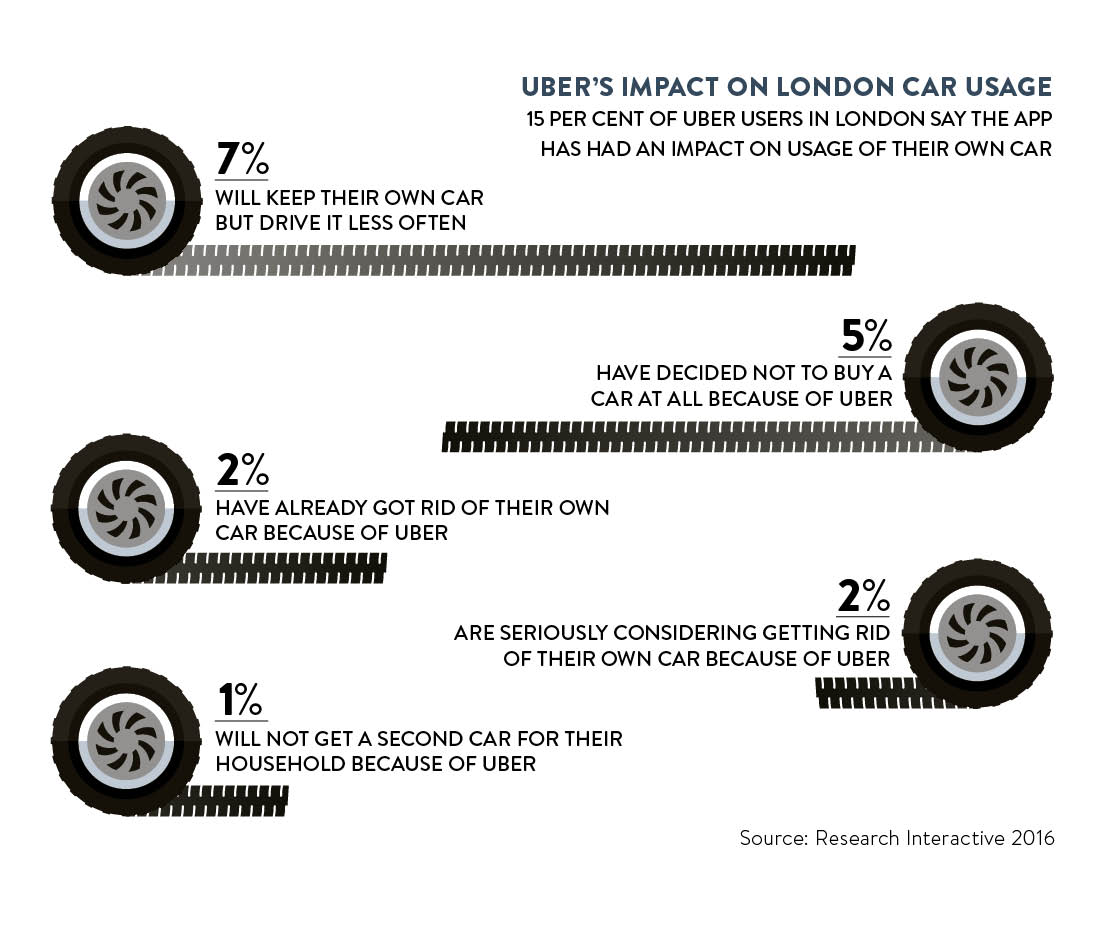

In London, the minicab-hailing app Uber says it has two million users. It claims research shows 5 per cent of current or former users wouldn’t buy a car because of the app. Black cabs also use apps like Gett, Kabee and Hailo.

Car clubs have also increased. Zipcar says it has 1,500 vehicles in the UK and it claims you can save £264 a month compared with owning a car. Nicholas Cole, president of Zipcar International, has high ambitions. “Our goal is a future where car-sharing outnumbers car ownership,” he says.

However, there are some concerns. City authorities recognise large numbers of car club vehicles and minicabs could increase congestion.

Referring to car clubs, Val Shawcross, the deputy mayor for transport in London, says: “I am a bit concerned that the business model might be set to change. Some are looking to park cars all over the place and leave them as massively available. That shift might be a step too far especially in inner London. We need to careful; are they reducing modal shift or increasing it?”

And there are warnings. Steve Gooding, director of the RAC Foundation, says cars that people own are still a vital way for them to get around.

He says continued investment in roads is crucial. “The car is the most common method of getting to work. Whether you believe cars help or hinder mobility and liveability, it makes sense to support investment in road infrastructure. Our paved surfaces are vital whether you get around on two wheels or four, on foot or on the bus, in car club vehicles or cabs,” says Mr Gooding.

So will city planners change their design; will we continue to see a shift away from vehicles? Will planning policies encourage developments around transport hubs so people don’t need cars?

In a number of inner London boroughs, such as Hackney, Camden and Tower Hamlets, some new developments are only given planning permission if they are car free. Residents aren’t given parking permits for their own cars, but they can be given reduced rates for car clubs.

Zipcar’s Mr Cole believes more cities will introduce these types of changes. “Urban planners are recognising again that streets should be designed for people and not vehicles, and we are already seeing many cities shifting towards better-managed urban growth, particularly in transport,” he says.

Dr Rachel Aldred, senior lecturer in transport at the University of Westminster, says city planners should continue to make streets friendlier for people and cyclists.

“In London and many other cities across the world we see people, especially the young, turning away from the car. Cars are less and less crucial to people’s identity, with car ownership and use levelling off or dropping,” she says.

“This means, though, that politicians and planners must think radically, seize the moment, and reallocate space and investment to efficient and healthier modes – walking, cycling and public transport.

“Crucially, we need to design mass car use, based on that old model of individual car ownership, out of our cities, instead prioritising liveability and health. Otherwise the cultural pendulum could swing back as car trips speed up or petrol prices fall and we’ll have missed the chance of a generation to change cities for good.”

Urban areas are changing and it’s being driven in part by public policy and the rise of sharing.

Evolving cities

Apps and car clubs