When Apple’s App Store went live in the summer of 2008 it kick-started a technology revolution that is still underway.

The combination of powerful smartphones and the ability to write apps for them, anything from games to business processes, has made entrepreneurs rich, given many struggling companies a boost by attracting new customers and helped drive efficiencies across several industries.

There are now more than three million apps available across Android and Apple’s operating system. Apple calculates that, since 2008, its App Store has generated almost $40 billion for developers, and created 2.6 million jobs across the United States and Europe.

And there’s little sign that the app economy is slowing down. The global mobile app market is projected to expand by 24 per cent to reach $51 billion in gross revenue across all app stores this year and hit $101 billion globally.

It’s much better to start with a clearly defined goal, a fundamental business model and an understanding of who the app is being built for

So apps are lucrative, but that doesn’t mean success will come easily as there are plenty of costly pitfalls for the unwary.

“We estimate there are about 40,000 new apps launched every month, so it is a crowded market and around two-thirds of all apps have only ever been downloaded a handful of times – we call those zombie apps,” says Jaede Tan, territory director in Northern Europe and the Middle East at app analytics company App Annie.

Clearly defined goals

The first step is to be clear why you want to build an app at all and to ensure that your reasoning is sound. There are plenty of bad reasons to build an app. Often someone, perhaps the chief executive, decides that a company must have an app, which forces people further down in the organisation to scramble around and find a reason for it. This will always lead to a bad outcome.

It’s much better to start with a clearly defined goal, a fundamental business model and an understanding of who the app is being built for. “You have to focus on the role,” says Dan Bailey, IBM UK’s mobile business director. “The one thing that’s massively different with mobile is this task-based function.

“What mobile gives you is a deeper level of context of where the person is and what the person is doing.”

The goal may be to generate revenue from the app itself, for example through consumers paying for it, or to improve customer loyalty through a free app, perhaps a game, which will also help a company understand more about their users. Or the goal may be to cut costs by building an app which streamlines a complex company process. All these are entirely valid, but completely different, app projects.

It’s also vital to validate these ideas with some research. If you were hoping to sell your app on an app store you might be disappointed to realise that over the last few years there has been a trend towards “freemium” apps that are free to use, but allow users to pay to upgrade for a better experience. Look at what other companies in your sector have done with apps, understand their motivations, and also what they have got right and wrong.

“Do your research, take the data and crunch it, and see what’s out there before because it is expensive to develop an app, and you don’t want to waste time and money on trial and error,” says App Annie’s Mr Tan.

Of course, if you are building an internal app, then your company’s choice of handsets will be the most significant factor. Smartphones pack huge amounts of potential into a huge package and it’s often hard to work out which features to use. Does your app need access to the GPS feature or some other sensor? This can make for a richer app, but drive up cost and complexity.

Getting the flow right

The next big stage is to start on the design of the user experience – what the user of the app will see and do. How do they log in? Do they swipe up or down?

Getting the flow of the app right is remarkably hard. Designs will often take many prototypes to perfect and rapid app prototyping tools exist for precisely this purpose. Depending on the complexity of the app, this stage can take weeks or even months to get right.

It’s vital to get as much input from everyone involved with the project as possible at this stage, and even more important to involve people who can bring fresh eyes to the design and who can often spot huge errors that you will be too close to the project to spot. Experts agree that this is the most critical stage of the project. Getting things wrong here can lead to very costly mistakes down the line when coding the app begins.

“If you don’t start with a clear understanding of what the user experience should be and what the design of your app should look like, then it doesn’t matter what kind of developers you pull in, you’ll end up with a bad app. Studies show that the user experience is one of the most important factors to get right,” says Burley Kawasaki, a senior vice president at enterprise app development company Kony.

About 70 per cent of the defects that crop up when you are building a mobile app are related to incorrect user experience design, he says.

Managing costs

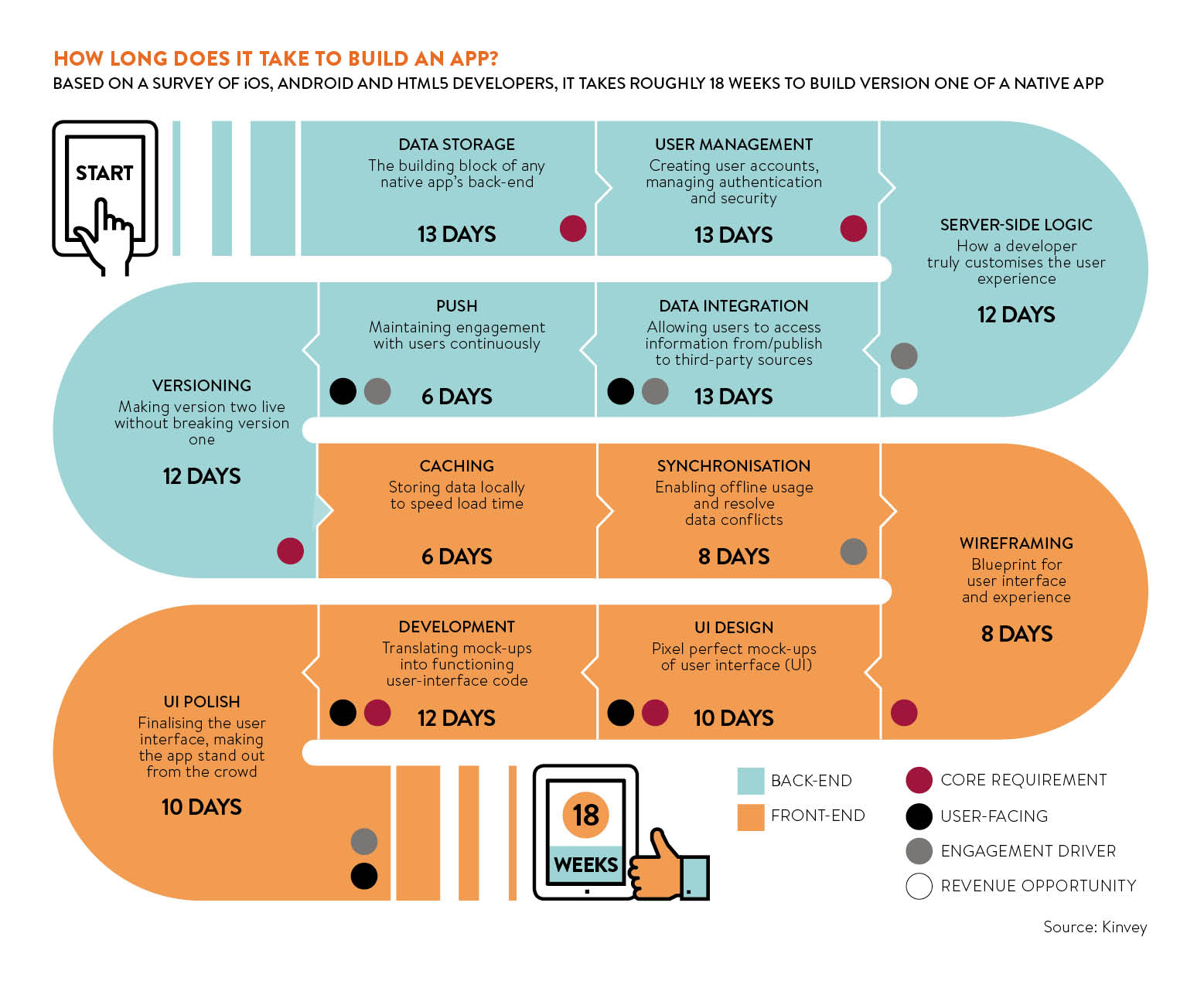

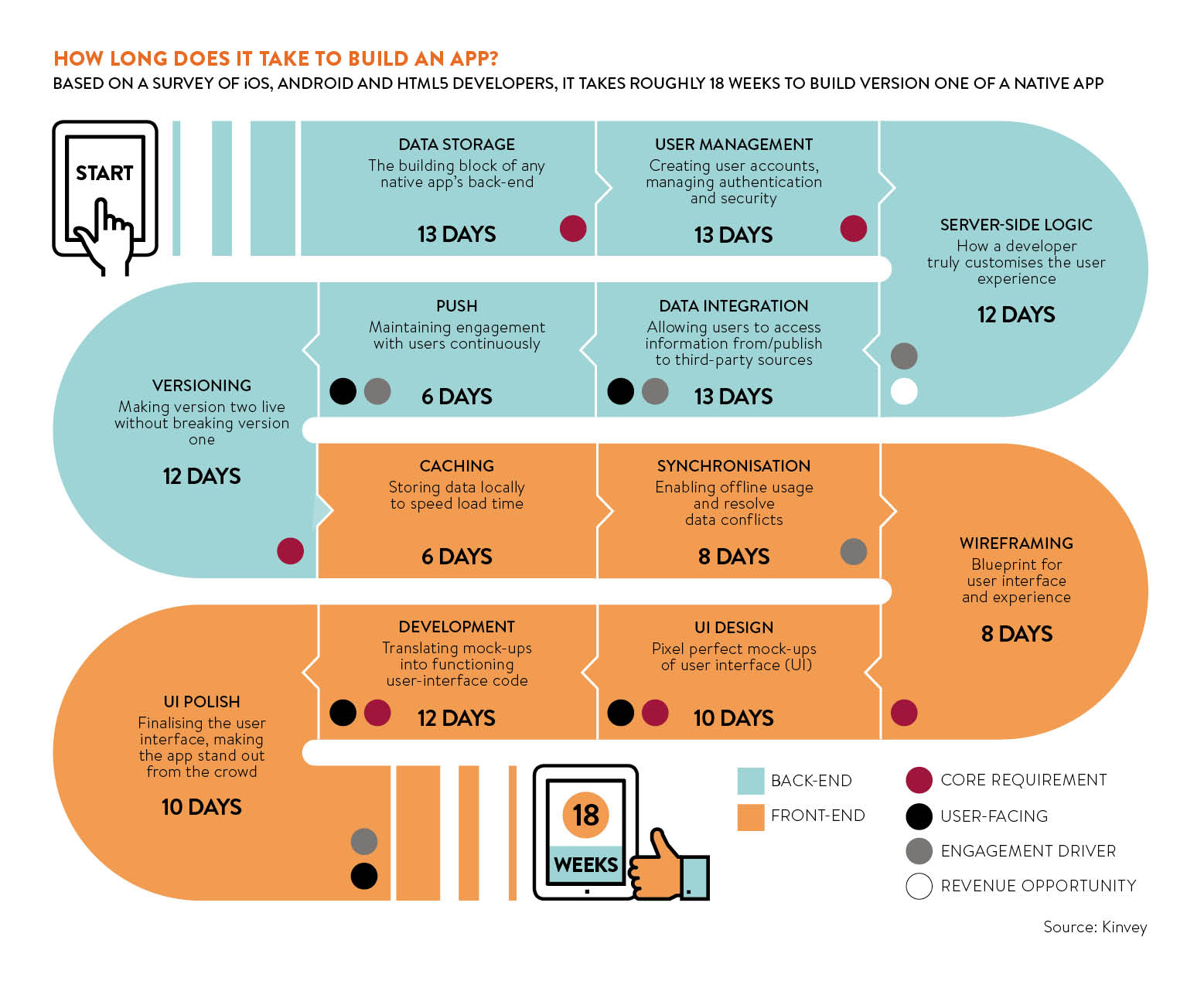

Once the design and user experience is settled it is actually time to code the app. Timescales and costs can vary wildly depending on the scale and quality of the app, and who is doing the work. For the flagship consumer app of a large company, costs can easily run into hundreds of thousands of pounds and even into the millions. For a small-scale app for a company to use internally, the costs can be much more modest, perhaps tens of thousands.

Often the best thing to do at this stage is to aim first for the minimum viable product, the most basic version of your app that will work well enough, and then add the rest of the functionality as fast as possible. This allows for more testing with real customers, allowing your development team to tweak the code as they go along in response to feedback. “Think big, start small and act fast,” says IBM’s Mr Bailey.

Often the best thing to do at this stage is to aim first for the minimum viable product, the most basic version of your app that will work well enough, and then add the rest of the functionality as fast as possible. This allows for more testing with real customers, allowing your development team to tweak the code as they go along in response to feedback. “Think big, start small and act fast,” says IBM’s Mr Bailey.

But building the app is potentially only one part of the cost. If an app needs to connect into your other enterprise systems, such as stock management or invoicing systems, then there could be a hefty bill for integration as well.

“It’s not just the cost of the labour to build what sits on the phone; studies show that the backend integration is often around 70 per cent of the effort and cost,” says Mr Kawasaki.

And even once you’ve finished, apps are not static. Many organisations update their app every few weeks with bigger updates once or twice a year. And operating systems are regularly upgraded which could break how your app works, so pencil in the cost of ongoing maintenance and development.

That’s not the end, either, so get ready to start learning again. As momentum starts to build around wearable devices, such as smartwatches and virtual reality headsets, you might have to start thinking about a new class of apps soon.

CASE STUDY: INPLOI

Inploi is a London-based technology startup building a jobs marketplace for the hospitality industry. People looking for work in restaurants, bars, cafés and hotels can sign up via the soon-to-be-launched app, while employers with positions to fill list their needs, and the app matches jobs to suitable candidates.

Inploi is a London-based technology startup building a jobs marketplace for the hospitality industry. People looking for work in restaurants, bars, cafés and hotels can sign up via the soon-to-be-launched app, while employers with positions to fill list their needs, and the app matches jobs to suitable candidates.

It has taken around six months to build the app with a core team of three and some additional help.

“We’ve learnt a lot along the way,” says Inploi co-founder Matthew de la Hey. “We’ve had to learn about the different languages and frameworks.”

He says it is important to get somebody on board with a firm technical background to be involved with technical decisions and conversations, such as whether to build a hybrid app or to go with separate “native” apps for Android and Apple’s iOS. “It’s about finding the right people to bring together in a team,” he says.

It’s also important to be agile and flexible when working on building an app, says Alex Hanson-Smith, Inploi co-founder.

“In terms of the design, we’ve been through multiple iterations before we arrived at a product that was ready for market. Prototyping tools have enabled us to test our design on a wide range of audiences – feedback is imperative to crafting a good user experience,” he says.

“I think it’s a mistake to go into anything like this with too firm an idea of what you want because that can blinker you to things that you ought to change, which you might not do if you are too stubborn about it.”

Clearly defined goals