Automation is the past, current and next big thing. For a long time, getting robots and software to work for us has been the Holy Grail of business. In theory it makes everything cheaper, more reliable, more powerful and it frees humans up to work on creative projects.

It’s not new. Ever since the first industrial revolution, capitalists have looked for ways to extract human labour from the means of production and replace it with smart systems.

This, of course, was initially driven by greed. Factory owners wanted to put a jack under their profit margins. Removing wages, the biggest cost in almost all businesses, was the best way to do it.

Today machines don’t just replace humans and speed up output, but are capable of working far beyond the human spectrum of ability

More recently new incentives have driven progress – reducing human error, improving health and safety standards, and by no means least importantly, saving the sanity of the poor beggars who stand day in day out on production lines attaching one bit of kit to another.

The 20th century saw the rise of the machines, typified at first by heavy milling equipment and pumping pistons, then by large mechanical arms in manufacturing capable of lifting cumbersome parts and screwing them into position with mundane, efficient regularity.

In the 21st century machine CVs have lengthened, their skillsets broadening into new areas. What they can do now is a quantum leap from what they could before the digital age – and the pace of change is accelerating.

Today machines don’t just replace humans and speed up output, but are capable of working far beyond the human spectrum of ability. This is thanks in a large part to the nascent internet of things and big data, which is producing machines capable of “learning” if not “thinking”.

Industry 4.0

It’s what is being called the fourth industrial revolution or Industry 4.0 to its friends. If you’re interested, the second revolution was in electricity and mass production, while the third was essentially the first part of the current digital great leap forward.

Once technology can make a determination from assembled data, it becomes tantamount to cognitive thought

“The combination of data, analytics and robotics will yield smarter, self-learning tools that perform judgment. Think claims handling, fraud detection, better buying decisions, improved complaints handling – the list is long,” says James Hall, chief executive of process automation business Genfour.

Technology will be able to deal with menial process-driven tasks initially, but is steadily gaining the capacity to take on more sophisticated projects.

“With speed to implement and low cost to run, we can start to tackle millions of roles that just perform rules-based processing,” says Mr Hall. “As we move up the intelligence scale, we could consider legal discovery work, mail room sorting, underwriting, medical diagnosis, financial and human resources advice.

“The list is extensive, with decisions based on data analysis and interpretation. Once technology can make a determination from assembled data, it becomes tantamount to cognitive thought.”

The impact of industrial AI

Asking machines to perform even simple tasks and equipping them with the intelligence to know when to change what they are doing has huge implications for the global labour market.

KUKA Robotics Corp’s Roboter industrial robot on show at Tokyo’s International Robot Exhibition

In the last 30 years, great chunks of the British manufacturing industry have been spun out to China, India and Eastern Europe. With automation, it will become materially viable to bring it all back again. Robots don’t want money, they don’t sleep and they can work in the dark.

Japanese technology company Seiko Epson has created a prototype that is an example of how manufacturing will evolve. “This autonomous dual-arm robot is 150 kilograms, with a tiltable head, two arms that can grasp objects and cameras for ‘eyes’ in its hands and head; this robot has the ability to recognise 3D objects and make visual inspections,” says Minoru Usui, Seiko Epson’s president.

“But most exciting of all, he can learn. In my view, a robot like this could help enhance the productivity of reshoring manufacturing firms, while also giving them a new flexible option for high-mix, low-volume production runs in a world where product life spans are becoming shorter and shorter.”

The company is also investing heavily in 3D printing and is reported to be planning the launch within the next five years of a machine capable of mass-manufacture.

“3D printers have the potential to revolutionise the manufacturing process and, coupled with autonomous robotics, the possibilities are endless,” says Mr Usui.

“They range from revised development and production lead-times, reduced supply chains and just-in-time solutions, to enabling solutions for immediate, one-off part production at remote engineering sites anywhere in the world.”

The evolution of manufacturing

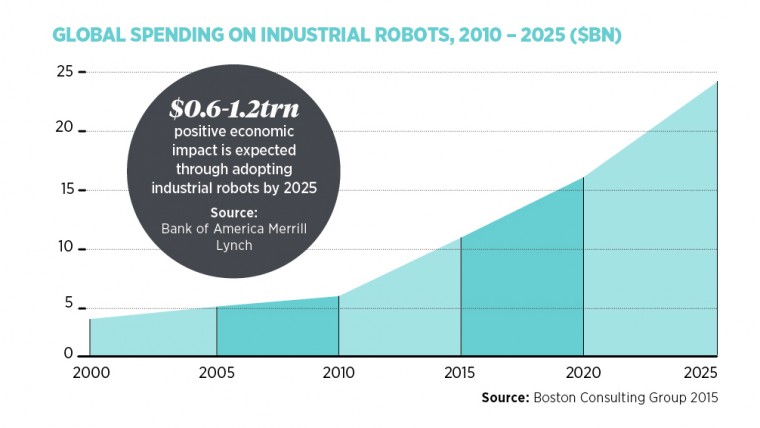

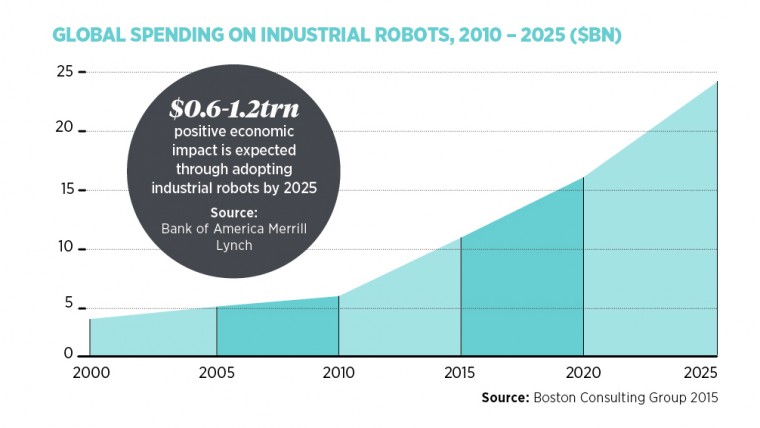

All this is making the robotics industry as a whole rather valuable. Bank of America Merrill Lynch calculates it will be worth almost $153 billion (just over £100 billion) by 2020, with robots performing 45 per cent of manufacturing tasks within ten years. That’s up from about 10 per cent today.

Research firm Gartner expects three million workers to be answering to a robot manager – or robo boss – by the year 2018. Meanwhile, Barclays says automation will “safeguard up to 73,500 manufacturing jobs in the next ten years and help address the skills gap in the sector”.

It adds up to a bright future for the production industries, says Antony Bourne, manufacturing global industry sales director at enterprise software business IFS.

Seiko Epson’s autonomous dual-arm robot

“Many factory processes are becoming automated, which allows companies to analyse their factors of production quickly, and communicate more effectively with customers and business partners,” he says.

“These processes span monitoring, co-ordination among different business units and management of product life cycles. Left to spreadsheets and manual legwork, these would be very slow and inefficient.”

Mr Bourne points to other sectors getting in on the act. One is professional services, in which robots could do a job performing searches, finding precedents, and discovering the best offers automatically from a broad range of historical and current sources.

That could make life a lot easier for accountants, auditors and lawyers, although it could also force them to create new points of differentiation to justify the loyalty of their customers.

Robots even have a place in the leisure sector, he says, as is the case with Japan’s Henn-na Hotel. Here a humanoid robot will help you check-in, a robotic arm will take your coat and an automated car transports you luggage to your room.

Access is gained through facial recognition, and rooms have smart lighting and air-conditioning systems that switch off automatically when you are not there. For some people it’s a vision of hell, but for many others it’s a sign of things to come.

A new industrial era

The UK sits in the automation pack, while countries like Japan and Germany are out in front. According to PwC, German companies are investing 3.3 per cent of turnover on Industry 4.0 and expect a yield of 12.5 per cent in return.

Tony Hague, managing director of PP Electrical Systems, says by adopting the same approach UK industry could be £20 billion better off. There are nevertheless good examples of businesses doing great things in the UK, he says, including Nissan’s plant in Sunderland and Jaguar Land Rover’s new engine facility in the West Midlands, both examples of “automated workplaces delivering world-class products”.

With quick advances in artificial intelligence, automation, robotics and the internet of things, it’s obvious the world has entered a new industrial era. It’s not science fiction or a prediction for the next century, it is here and now.

But so quick are modern cycles of innovation that naming each new stage will become pointless. Industry 5.0, 6.0 and 7.0, each a distinct and significant technological upgrade from the last, will not be 100 years in the making, but a decade or less apart.

Industry 4.0

The impact of industrial AI