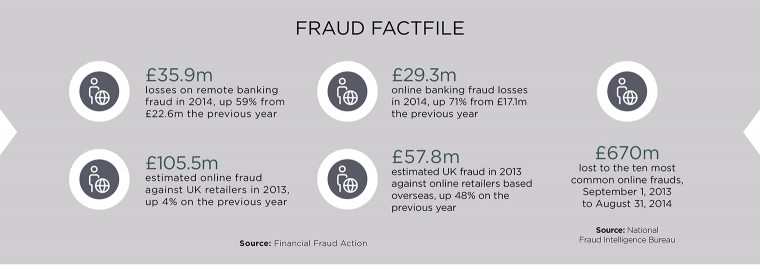

Banking fraud is a problem as old as banks themselves. Frauds against UK online banking customers netted £60 million in 2014, a 48 per cent increase on losses in 2013, according to Financial Fraud Action UK, an industry body. The organisation warns that individuals are leaving themselves open to fraudsters, by falling victim to phishing e-mails asking for account details or by failing to install effective anti-virus software.

And, with more than half the adult population now using online banking, fraud is likely to grow. Rising losses and the distress caused to customers are prompting banks to look at more robust security measures, including biometrics.

A problem banks face is that online fraud has grown as banking and financial services have become more anonymous and automated.

As one expert in the sector points out, in the days of personal banking and local branches, we had a very effective form of biometric security: a bank manager who recognised their customers. If a bank teller became suspicious of a customer, he or she could call on the manager, who would vouch for the customer or raise the alarm.

Online banking takes away that personal relationship, forcing banks to rely on passwords and other electronic security measures. Unfortunately, passwords are easy to forget and also easy to crack.

“Banks have been overly reliant on PINs and passwords since mainframes first came in, in the 1950s,” says Mike Wood, a director at IT firm Unisys. “Banks then moved to PINs and ‘memorable’ information. Unfortunately that information is often instantly forgettable and people can’t recall it when they need to. It is flawed.”

To help us remember PINs and passwords, we write them down on sticky notes, store them in spreadsheets or reuse the same passwords over and over. All this makes life harder for the customer, but easier for the fraudster.

Banks’ attempts to bolster security, though gadgets such as PIN readers or security dongles, only add to the inconvenience. “These things are complicated, so often we just won’t use them,” says Mr Wood.

Biometrics are, at least on paper, hard to hack, but also convenient to use

The problem is becoming worse as consumers start using cards and mobile phones for contactless payments on the move. In the UK, contactless payments have no authentication at all if they are less than £20; it is sufficient for someone just to have the credit or debit card.

Phone-based payments could, potentially, support higher-value transactions, but only if security can be addressed. Anything more complicated than entering a standard, four-digit PIN probably will not appeal to consumers trying to pay with a smartphone. Requiring them to enter a strong password – even if they could remember it – might make them abandon the transaction.

This is prompting banks to look for alternative security measures, ideally those that are both hard to hack and easy to use.

Biometrics are, at least on paper, hard to hack, but also convenient to use. Coupled with smartphones with fingerprint readers or computers with webcams, they might not even need banks to give their customers additional hardware.

“Any reliable mechanism that is easier than a password is a good thing,” says Dr David Chismon from security consultancy, MWR InfoSecurity.

Already, some banks allow their customers to authorise transactions with a fingerprint and fingerprints are also under consideration as a way to secure smartphone payments.

Unfortunately for advocates of biometric security, as well as for banks’ anti-fraud departments, biometrics is neither completely secure, completely reliable nor as easy to set up as they might hope. Of the dozens of biometric security trials carried out by banks, only a handful have led to successful, large-scale deployments.

The first challenge banks face is enrolling customers in biometric programmes.

The last few years have seen plenty of new biometric tools join fingerprints and iris recognition. These include advanced voice biometrics, and palm and finger vein readers, systems that read heartbeats, breath sounds, and even the way we write or type, a science known as “behavioural biometrics”. As Steve Silberstein, chief technology officer at tech firm SunGard, points out: “The body is full of interesting ‘fingerprints’.”

But to make these systems work, banks have to capture the customer’s biometric ID, as well as check they are who they claim to be. This process is time consuming, expensive and often disliked by customers.

“Enrolment is one of the big challenges. If you have ten million customers, and have to capture their voice prints, that is a significant effort,” cautions Steve Nicholls, at consultants Deloitte.

And biometrics, despite the way they are portrayed in science fiction or detective novels, are rarely completely accurate.

Biometrics work on a balance of probabilities or “score”. “They don’t always work,” explains Johnny Wyld, a senior consultant in the financial services practice at PA Consulting. “A password or PIN is either right or wrong. Biometrics produce a percentage score, which the bank has to decide whether to accept – and the customer feels horrible if they are rejected.”

Factors as diverse as background noise to the sweatiness of a palm, can affect a biometrics’ accuracy. Banks have to decide whether to accept a lower score – and a higher risk of fraud – or a tougher biometric and the risk of inconveniencing genuine customers, and forcing them back to passwords or memorable words.

“I can’t use the fingerprint reader on my iPhone if I’ve been running,” says Tracy Hulver, chief identity strategist at Verizon. “We need a biometric that doesn’t have that problem.”

It is even possible to fake some biometrics, such as smartphone fingerprint scanners, using little more than sticky tape and glue, warns Candid Wueest, a researcher at security firm Symantec. “That means you can unlock the device, unlock online banking and start a transaction,” he says.

This means, at least in the short term, banks look set to use biometrics alongside other checks, such as background checks on transactions, smart cards or phones, and even the humble password. “It has to be seamless, but also allow the customer to keep control,” Accenture Technology Labs’ Emmanuel Viale concludes.

POINTING THE FINGER AT RETAIL PAYMENTS

PayPal is one of the best-known names in online payments and is used for thousands of transactions every day, especially on eBay.

But PayPal is also trying to build an offline payments business, for example by supplying card readers to small businesses and retailers. In addition, PayPal customers can use the company’s app to pay for goods and services, including meals at the Pizza Express chain.

Last year, though, the company went a step further and added fingerprint approval to its app. The service was set up initially to work with selected Samsung smartphones and tablets because they have built-in fingerprint readers.

The system is designed to replace user names and log-ins, otherwise, anyone wanting to pay by PayPal would have to remember their sometimes complicated computer-based PayPal credentials in a retail store.

The scheme was originally planned for roll out in 25 countries, and was supported by an authentication scheme called FIDO, which was also backed by Google, Microsoft and MasterCard.

However, although other firms have since turned to smartphone fingerprint readers to authorise transactions, including Apple’s Apple Pay in the US, security researchers claim the fingerprint system on the Samsung S5 – the launch device for PalPay’s scheme – was allegedly easily hacked.

Researchers were able to photograph a fingerprint on a user’s phone and create a false print to unlock the handset. However, given the sophisticated tools hackers would need to do this and that they would need to capture the user’s fingerprint in the first place, the risks to users could still be minimal.

CASE STUDY: FEELING THE HEARTBEAT

Halifax, part of the Lloyds Banking Group, became one of the first companies to use customers’ heartbeats as a biometric identifier earlier this year.

The bank has tested out a device called a Nymi band, to capture heartbeats and use them instead of PINs or passwords.

The Nymi band is similar to wristbands worn by athletes to monitor their heart rate for sports training, but it has been developed specifically to create a heartbeat-based authentication system, which the company calls HeartID. This uses the customer’s electrocardiogram, or ECG, which is unique to each of us. The band itself communicates wirelessly with a computer, smartphone or other device.

The system will be used by selected Halifax customers as a way of logging on to online banking on their computers or to authenticate themselves on the bank’s smartphone app. It checks both that the customer is wearing the band and the software recognises their heartbeat.

Although the Nymi-band system is being used for online and smartphone banking, it has the potential to be employed more widely, for example to replace PINs at cash machines or even to pay for transactions in shops, provided banks and stores are willing to invest in readers to pick up the band’s signal.