1. BP

The first chapter of any book on preventing a crisis turning into a public relations disaster has to be devoted to BP and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The explosion on the Gulf of Mexico oil rig in April 2010 killed 11 and led to multi-billion compensation payments by the British oil company.

The gaffes of BP chief executive Tony Hayward dominated the headlines and contributed to his replacement within six months.

Mr Hayward may have thought his comments reasonable, but they lacked empathy and appeared “tone-deaf” on their likely effect.

Asked what he would tell people in Louisiana, Mr Hayward replied: “We’re sorry for the massive disruption it’s caused their lives. There’s no one who wants this over more than I do. I would like my life back.” This did not play well with relatives of the dead.

Mr Hayward was also over-optimistic about how quickly the well would be capped and minimised the environmental consequences.

The BP chief executive claimed the impact would be “very, very modest”. The Gulf of Mexico was a large ocean and could easily handle the volumes of oil and dispersant involved. True, eventually, but tell that to Louisiana fishermen scared of losing their livelihoods.

BP compounded the personal errors by launching a glossy multi-million network TV campaign. US President Obama noted the money would have been better spent on the clean-up.

In those and other personal and corporate gaffes, BP failed to show sympathy, understanding or humility and even initially appeared reluctant to accept full responsibility, instead blaming contractors.

2. CHRISTMAS FLOODS

The credibility of Sir Philip Dilley, chairman of the Environment Agency, gradually drained away during the unprecedented Christmas floods in the north west of England last year.

As thousands faced a Christmas without electricity or even their homes, Sir Philip resolutely stayed in his holiday villa in the Caribbean and declined to return to either his office or the scene of the disaster.

That sent an unfortunate message, but it was the efforts of his press staff to obfuscate over where he actually was that led ultimately to his position becoming untenable.

One disingenuous statement said: “Sir Philip is at home with his family”, a comment that was economical with the truth.

Sir Philip was at his second home in Barbados and denied staff had advised him not to go away for Christmas because of severe weather warnings.

He finally returned to the UK on December 30 and later told MPs he didn’t feel away in the Caribbean and often worked from his home there.

He accepted he should have returned “one or two days earlier” and conceded the holiday was “a PR disaster”.

Sir Philip resigned on January 10, claiming expectations of his £100,000, three-days-a-week job had changed to mean he had to be available “at short notice throughout the year”.

In this case the symbolism of leadership is everything. In the face of such devastating floods the chairman of the responsible agency cannot remain in sunny Barbados as if nothing had happened.

Attempted cover-ups and anything less than total honesty always make matters worse.

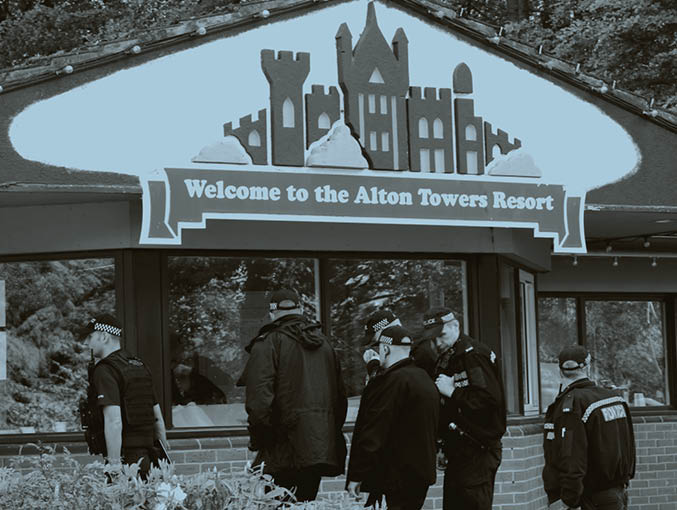

3. ALTON TOWERS

For theme park owners, serious accidents are always damaging because, however rare, the last thing anyone expects is that a day’s entertainment should lead to life-changing injuries.

Yet by general consent Nick Varney, chief executive of Merlin, owners of Alton Towers where the accident on The Smiler ride happened last June, handled a difficult situation well.

Mr Varney, who set off for Alton Towers immediately on the day, said he was “totally devastated” by the accident.

Detailed statements were issued on what had happened, Mr Varney himself fronted numerous broadcast interviews and communicated widely by social media. The decision to close the entire park, rather than just the ride, until it was better understood what had happened, was announced on Twitter. Safety controls were also improved.

Mr Varney showed both sympathy and understanding, and concentrated on the four seriously injured victims rather than the plight of the company.

Asked about the Merlin share price, Mr Varney responded: “You’ll forgive me if I am not really focussed on the share price at the moment.”

Without waiting for an investigation or formal legal assessment, Merlin immediately accepted “full responsibility” for the accident and confirmed it would pay compensation to all those injured.

Letters to that effect were hand-delivered to the homes of those affected. Merlin said it had tried to respond in a “sensitive and appropriate” way, and the company won public respect as a result.

On the first day after Alton Towers reopened, there was a neat touch – free tickets for the early returnees.

4. TALKTALK

Opinions were very divided on the performance of TalkTalk chief executive Dido Harding when she appeared on radio and television to discuss the hacking of the phone company’s confidential customer records.

The crisis was potentially existential for the company, with records of more than four million customers possibly compromised last October.

By touring the studios without knowing precisely what had happened, Ms Harding appeared to be breaking one of the basic rules of crisis management – know the facts first before you pronounce.

Ms Harding declared herself “uncertain about the technical nature of the attack”, did not know how many were affected, while conceding it could be all 4.2 million, and acknowledging “she did not know how much of the stolen data was encrypted”.

To make matters worse she faced questioning about whether TalkTalk had done enough to improve security after previous recent hacks.

Yet Ms Harding took full responsibility as chief executive, and faced the music on television and before a House of Commons select committee on what she emphasised had been a criminal attack.

As senior PR professional Ian Hood said: “Harding was honest, open, apologetic and didn’t hold back.”

That honesty and openness trumped critics who said she had looked like a rabbit in the headlights.

Teenagers were convicted for the hack that actually involved around 400,000 records, 100,000 TalkTalk customers were lost and there was a £60-million hit to the company, but Ms Harding and TalkTalk survived.

1. BP

2. CHRISTMAS FLOODS