First came Brexit. June’s shock decision by the British electorate to leave the EU, bringing a close to a 40-year membership and precipitating the biggest ever one-day fall in the value of sterling in the pound’s history.

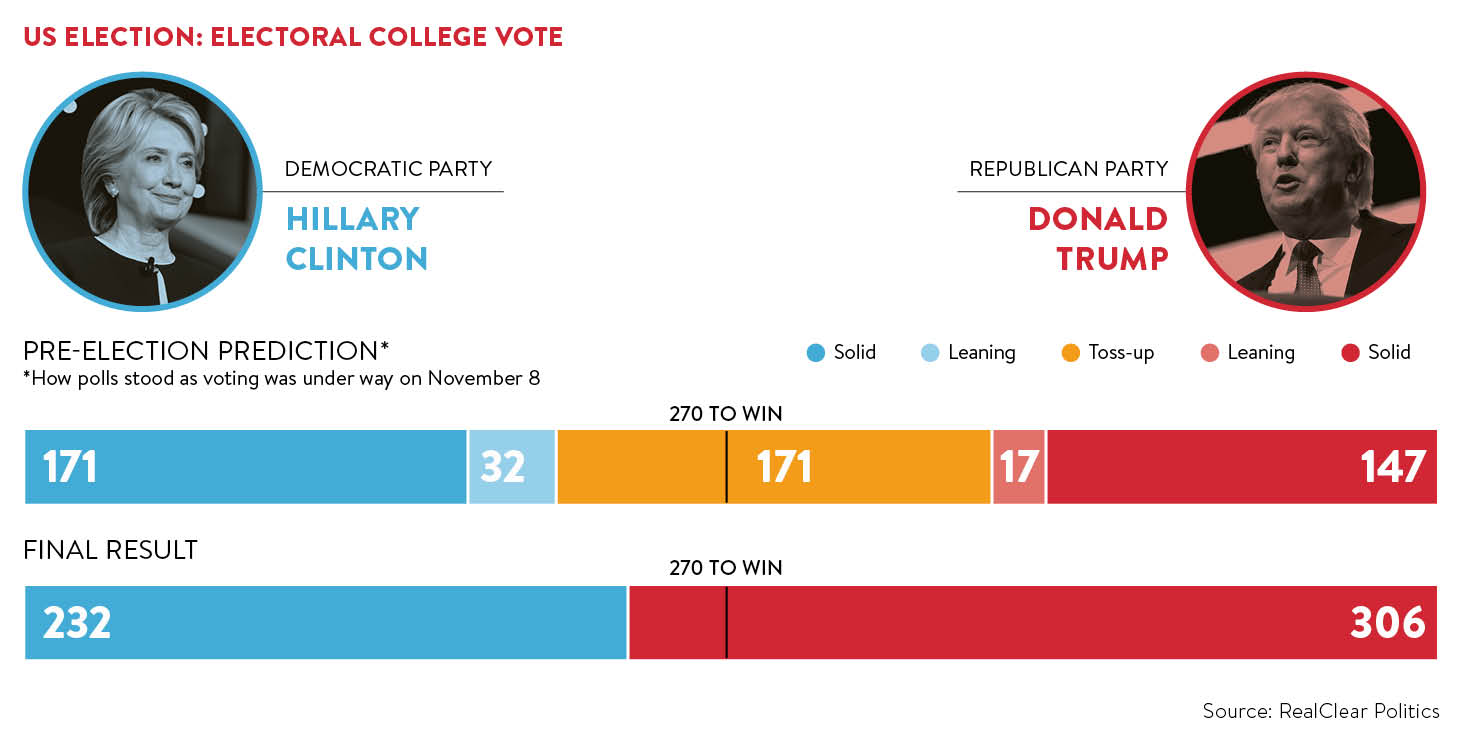

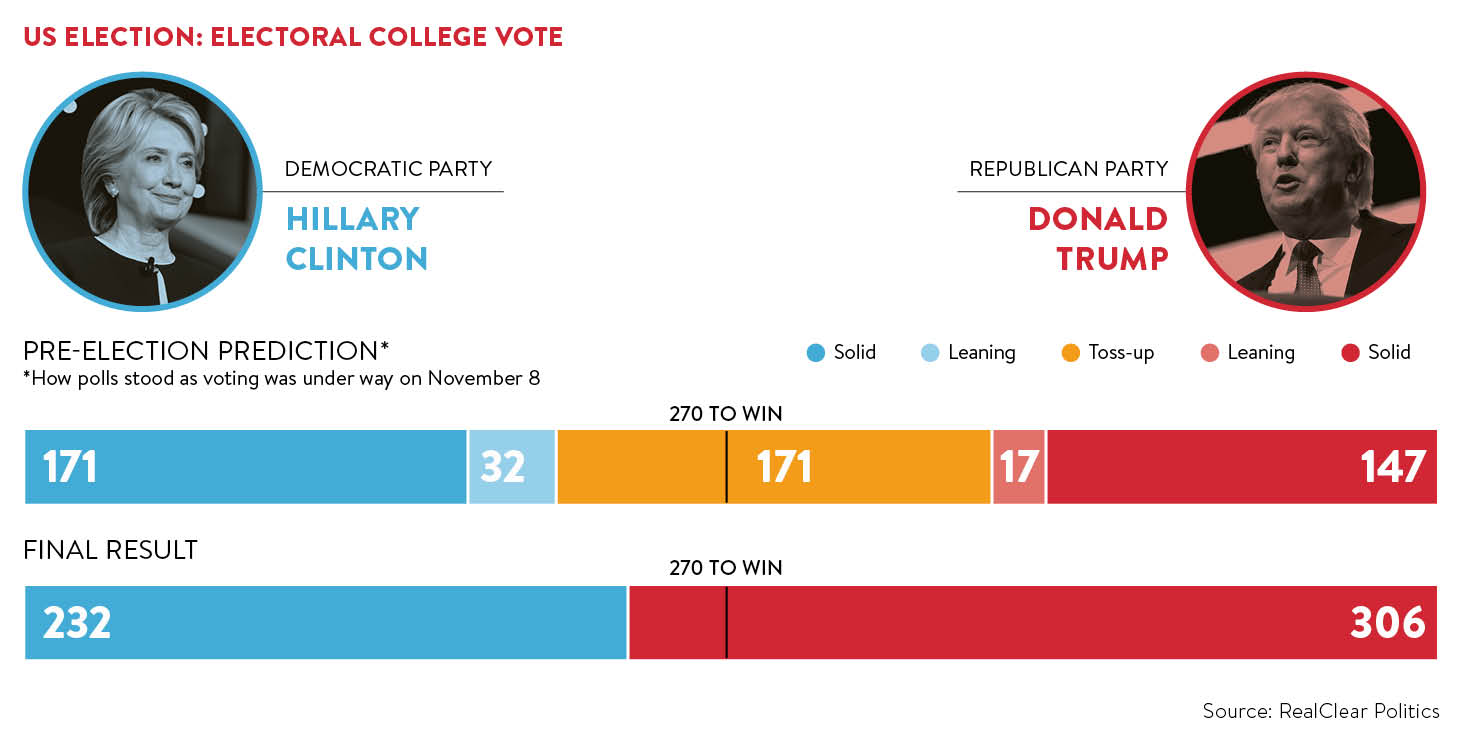

Then came Trump. The United States’ most controversial, combative and divisive election campaign in living memory, if not ever, ended with another body blow to the political establishment.

Markets, the media and citizens worldwide are left contemplating what’s next. President Le Pen? Frexit? Italeave? While commentators continue the increasingly difficult task of forecasting the answers, other questions demand attention: will the issues underlying this instability extend beyond just the political arena, and what might this mean for brands and businesses?

Influencing factors

It’s important to first understand the forces behind our current context. There are two basic theories influencing the recent rise of populist opinion and anti-establishment sentiment, discussed in a working paper from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

The first relates to economic inequality, brought on by a combination of growing disparities in income and wealth, automation of manual labour, the rise of the knowledge worker, and the impact of globalisation on labour, people and capital flows. The second relates to cultural backlash, where once predominant sectors of the population react to the rise of progressive values, such as cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism, and perceived erosion of their traditional values.

No matter which is more prevalent, both have the potential to influence more than just our political opinions and affiliations. So how do businesses respond? Are populism and anti-establishment feelings – so well capitalised on or exploited by Farage, Trump and Le Pen – an opportunity for businesses or are they a threat? Is seizing on this emerging aspect of consumer sentiment a path to disruptive brand differentiation or does it offer more risk than reward? Could Brexiters be considered a new segment, ripe for those brands able to appeal to their frustrations or are political beliefs largely unrelated to brand choice?

The political business

We’ve already started to see examples of brands’ actions being interpreted as political commentary and some of the consequences. In the UK, the campaign group Stop Funding Hate actively lobbies brands to withdraw advertising from several right-wing tabloids, over what it claims are divisive hate campaigns. It claimed victory recently when LEGO tweeted the campaign, saying “We have finished the agreement with the Daily Mail and are not planning any future promotional activity with the newspaper”, only for the toy manufacturer to find itself subject to criticism from Conservative MP Andrew Bridgen for attempting to compromise the integrity of a free press. Similarly, Kellogg Company has found itself the subject of an aggressive boycott campaign by US far-right online media brand Breitbart News, after withdrawing its advertising from the site, saying it “wasn’t aligned with our values”.

The real question for business leaders is less about whether to take a page from the populist political playbook and more about whether you’re truly in touch with your customers

Richard Huntington, chief strategy officer at advertising powerhouse Saatchi & Saatchi, offers a word of caution. “My first instinct is to say ‘let’s not panic just yet’. What we’re witnessing is a counter-culture, not a dominant culture. Counter-cultures are important and need to be listened to and understood, but I certainly wouldn’t advise that anybody jump on an anti-establishment bandwagon, because it’s not clear what this is yet.

“Some people have indeed been left behind by recent progress, so is this a case of them flexing their muscle, or is this the beginning of a fundamental recalibration of Western culture, where we move from a period of greater openness to one of greater insularity? I don’t think we can yet call that, and I think it would be unwise for businesses and brands to pander to this phenomenon yet.”

Really understanding your customers

Jez Frampton, global chief executive at leading brand consultancy Interbrand, concurs and points to a return to some fundamental tenets of customer-focused thinking, which appear to have fallen out of fashion. “This all comes down to understanding people, let’s call it the ‘knowing-your-audience lesson’. I spoke recently at a conference and asked the audience how many of them had sat in on focus groups, depth interviews or customer meetings in the last month – in other words, really saw customers, rather than sitting in isolation reading reports and web stats and the like. Only about 10 per cent or less of the room put their hand up and this really caught me by surprise,” he says.

“If I had asked that question 15 to 20 years ago, the answer would have been the opposite – 90 per cent of the room would have raised their hand. We’ve got so much fantastic data and technology at our hands that it’s almost become an excuse for not going out and touching the hands of our customers. Most people talk about the wealth of data they have, but then go on to say that they’re lacking the level of insight they need to understand it.”

While there’s already no shortage of articles about marketing lessons from Brand Trump, the real question for business leaders is less about whether to take a page from the populist political playbook and more about whether you’re truly in touch with your customers.

As businesses have developed evermore sophisticated ways of profiling and understanding their audiences, the promise of technology – bringing us closer to our customers – has actually, for many organisations, reduced their proximity to genuine insight and weakened the natural customer sensitivity, which marketing and brand practitioners had to rely on in our analogue yesteryear.

Data failures

Not only has the gulf between a brand and its customers widened, the data in which businesses often blindly place faith has also shown its shortcomings. The recent and dramatic failings in pollsters’ abilities to gauge and predict public opinion accurately has raised something of a question mark over the reliability and validity of audience research. From the UK 2015 general election to Brexit to Trump, the traditional and data-reliant methods of understanding and predicting human opinion and sentiment have fallen short, calling into question the trust which businesses place in surveys and quantitative data alone.

“If there’s a lesson, it just goes to show how completely wrong polling can be, which in the corporate world is the essence of most customer research, segmentation and the like,” says Mr Frampton. “The reality is you need that ‘texture’ which data alone can’t provide, and this requires you to invest time with real people and start listening again.”

Saatchi & Saatchi’s Mr Huntington agrees, suggesting one of the biggest takeaways from recent political disruptions is the need for a return to empathy, greater diversity of thought and a step back from our over-reliance on data alone.

“Organisations need to have greater genuine empathy towards the people they serve and look after. Just as ‘echo chambers’ exist in the world of social media, so do they in the corporate world. The same perspectives echo around a business and are often taken for granted, yet no one’s really listening to their customer. It’s that breakdown in empathy that can lead to real issues being missed.”

Ask yourself. How many meaningful customer conversations have you had in the last six months? How much exposure do you get to real people, beyond the statistics and data? Are you asking the right questions and are you really listening to the answers? Interbrand’s Mr Frampton concludes: “Be careful if you think you know your customer that well – most companies could do a lot more to understand them better.”

Influencing factors

The political business

Really understanding your customers