If you want to be a millionaire, start with a billion dollars and launch a new airline. So says Sir Richard Branson, recounting his experience of setting up Virgin Atlantic.

Taking aircraft purchase costs as an example, even the relatively small Airbus A320 has an average list price of £63 million, while the newly launched A350-900 is £199 million and the A380-800 £279 million.

Clearly these birds are expensive to buy and operate, so the revenue-generating potential of every inch of cabin space needs to be carefully considered, especially with regard to fitting the optimum number of seats – a factor that is absolutely critical to an airline’s revenues and survival.

There are airline teams dedicated to directing and evaluating cabin configurations, which draw upon a wide range of skills, including mathematics, economics and forecasting passenger trends. Their work is something of an art and involves many complex calculations, but some basic key factors can help give a sense of how it all works.

In airline parlance, each seat on an aircraft flying one mile represents an available seat mile (ASM) and each paying passenger flying one mile represents a revenue passenger mile (RPM). Dividing RPM by ASM gives the load factor, which indicates how full an airline’s planes are, and dividing ticket revenues by RPM establishes the yield (even a full plane isn’t profitable if the fares paid are too cheap). Multiplying that yield by the load factor gives the revenue per ASM (RASM), which shows how much money each seat is earning the airline. The final key calculation is the cost per ASM (CASM), arrived at by dividing total airline operating expenses by ASM.

With load factors of around 66 per cent required for many airlines to break even on a flight, each extra seat filled represents profit

According to the International Air Transport Association, in 2014 the average airline load factor was 79.2 per cent. A high figure, but that extra 20.8 per cent represents a lot of unrealised potential revenue. After all, with load factors of around 66 per cent required for many airlines to break even on a flight, each extra seat filled represents profit. So how can airlines squeeze more seats into their cabins?

Airlines with business and first class want as many passengers as possible flying in those lucrative cabins. Their plush seats may take up more cabin space than those in economy, but with ticket prices up to five-times higher on long-haul routes, they generate a high RASM.

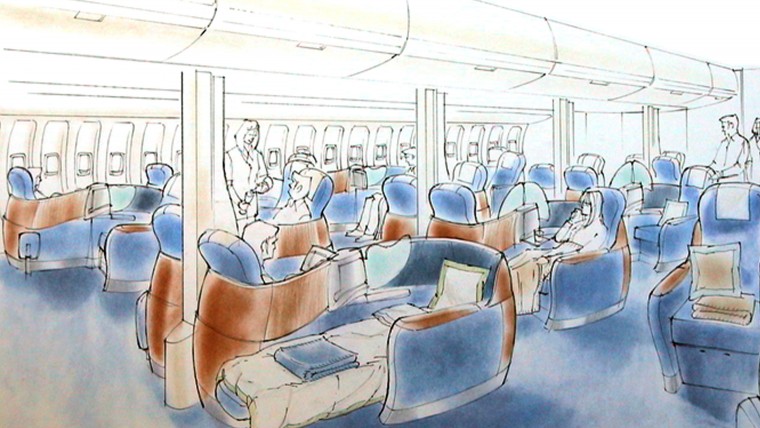

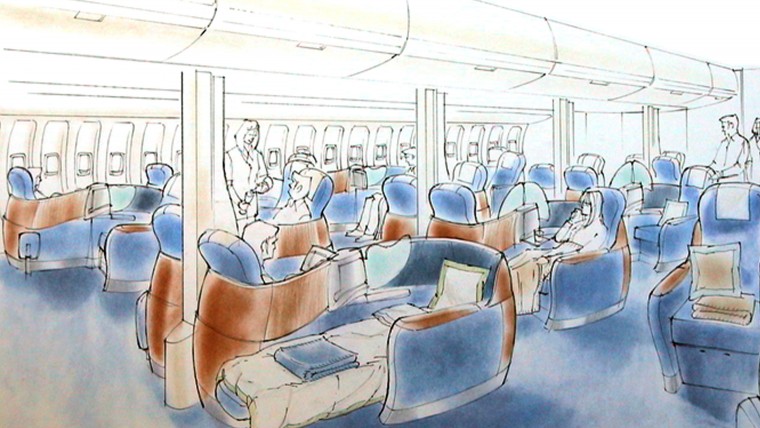

Long-haul business class is a particularly interesting sector at the moment, with myriad new designs appearing every year, featuring flat-bed functions, large HD TVs, some even with a footstool that doubles as a seat so a companion can join you for dinner. Luxury is one thing, but the really clever part of the designs is their space efficiency – remember, the more seats they have available to fill, the more profit an airline can make.

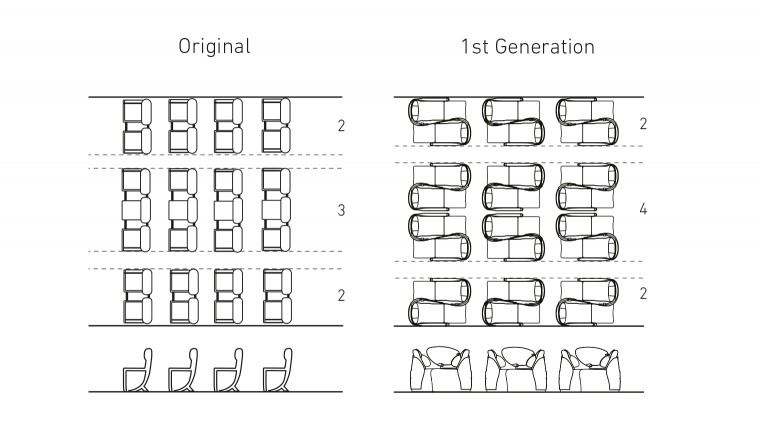

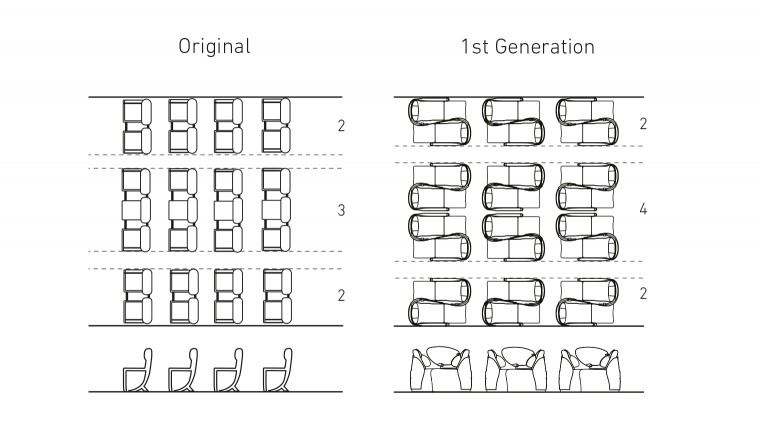

Perhaps the best example of a space-efficient seat design is British Airways’ Club World, which was a landmark moment for the airline – and for commercial aviation – when it launched in 2000, as it was first business-class seat that could convert into a fully flat bed. The distinctive forward-aft configuration, sometimes called “yin yang” due to its shape when viewed from overhead, was devised by the Tangerine design consultancy in London to maximise passenger comfort and cabin density.

Other airlines have introduced their own solutions to reaching the ultimate compromise of passenger and fiscal appeal, such as Virgin Atlantic with its Upper Class Suite, while many others choose the more “off the shelf” seats offered by airline seat manufacturers, which are still innovative and space efficient.

Illustration showing British Airways ying-yang beds

Original concept drawing of British Airways ‘ying-yang’beds

Such is the efficiency of modern business-class seats that many airlines are finding their consistently high load factors and RASMs more attractive than those of first class, and are phasing out first class from some routes, while some are dropping it completely. As carriers vie for business-class custom, the product is evolving into “super business”, great examples of which can be found on Qatar Airways, Etihad Airways and Singapore Airlines. However, as business class has increased in luxury, for airlines still keen to cater for the top tier of flyers, first class has also had to move forward accordingly.

At the other end of the scale, in theory, cabin configuration should be simpler for the “pack ‘em in, sell ‘em cheap” low-cost carriers, who need the maximum number of economy seats on board to get a return on those low airfares. But without advances in the cabin-space efficiency of economy seats, these carriers can soon reach a plateau in cabin capacity.

Some seat manufacturers are leveraging the thin and strong properties of composite materials to make the seatbacks of economy seats more sculpted, in order to carve out as much knee-room as possible. By creating that space, the space between seat rows can in turn be reduced, meaning that additional rows of seats can be squeezed into the cabin without, airlines claim, loss of comfort. Even lavatory walls are being sculpted to create space for another row of seats – every square inch of cabin space really is evaluated for its potential to make money.

However, there are further complications when packing in extra passengers, including safety regulations such as the US Federal Aviation Administration’s requirement that flights must have a minimum of one flight attendant per 50 seats and all passengers must be able to evacuate the aircraft in 90 seconds or less using only half the exits.

Many new and innovative aircraft seats are introduced every year, all built around the key considerations of how they can be attractive to passengers and profitable for airlines. Look around you on your next flight to see how strong the load factor is. If you’re in economy and the load factor is weak, then who knows, you might even be upgraded to business class. Just don’t let the thought of the low RASM put you off the champagne.