When the Premier League wanted a new chairman it sought the best possible candidate. This meant looking beyond the confines of the football profession. Men and women with a diverse range of skills and experience were considered. The Premier League’s choice was Anthony Fry, a former investment banker, who serves on the BBC Trust, is chairman of Dairy Crest and has held numerous non-executive and advisory positions. Fry was schooled in history at Oxford University rather than the Manchester United Academy. His unique and diverse set of skills made him the ideal candidate for what is likely to be a demanding job.

The appointment followed a trend. Businessman Lord Paul Deighton was appointed to lead delivery of the London Olympic Games. As an outsider, he was chosen for his wealth of knowledge and experience. As we all know, the London games were stupendously successful.

Yet far too many UK boards are still rejecting this approach. They prefer to stick with hiring insiders, all too often clones of the existing board members. It is an approach which makes no more sense than a football team selecting 11 goalkeepers.

How bad is the problem? Gender is just one measure of diversity, but an important one. Until recently, the proportion of women directors of FTSE 100 companies hovered just above 10 per cent. Board nominating committees, however, have demonstrated a refreshing willingness to tackle this low percentage, prompted at least in part by the government-backed Davies Review of Women on Boards, led by former Standard Chartered chairman Lord Davies. As a result, the numbers have climbed significantly so that women now account for more than 17 per cent of directorships in the FTSE 100, a rapid acceleration compared to previous years. More undoubtedly remains to be done, particularly in terms of appointing more female executive directors, where the numbers remain stubbornly low.

Board diversity is more than mere biology, age or qualifications; it is about finding the most potent mix of experience and personalities

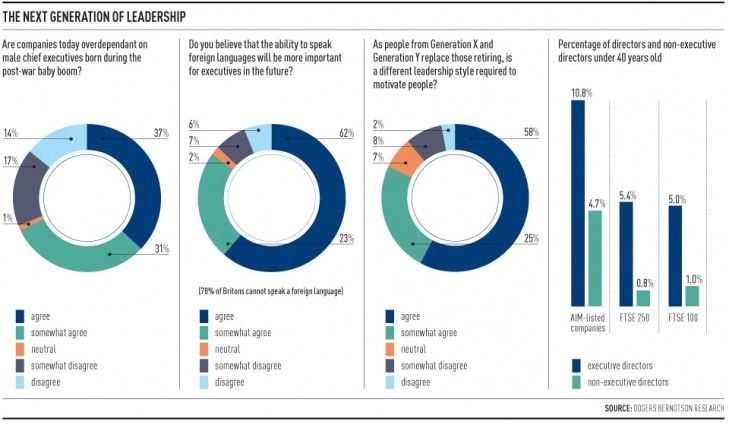

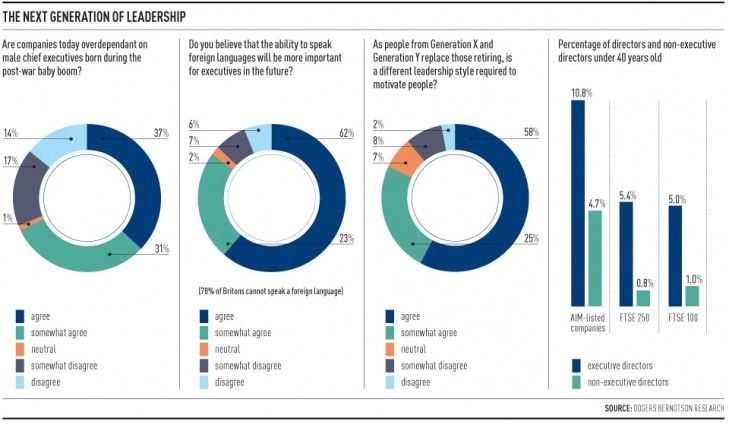

Of course, gender is only one aspect of board diversity, which should be considered in its widest sense. Younger directors, for example, can provide fresh perspectives that challenge existing thinking. Research from the executive search firm Odgers Berndtson found that in AIM listed companies, 10.8 per cent of executive directors and 4.7 per cent non-executive directors are aged under 40. In the FTSE 250, 5.4 per cent of executive directors and 0.8 per cent of non-executive directors are under 40. In the FTSE 100, the numbers fall further, with 5 per cent of executive directors and only 1 per cent of non-executive directors below that age.

Firms clearly know something is wrong. After the Baby Boomers, a recent global report by Odgers Berndtson, revealed 43 per cent of executives believe their senior management team is not “future- proof” and 91 per cent say their firms will need to attract the best people. Even language skills are a struggle for UK firms. Almost two thirds say the ability to speak a foreign language will be increasingly valuable, yet the British Council’s latest figures show 78 per cent of Britons can’t speak a foreign language and foreign languages have experienced the fastest fall of any faculty in universities, something the Confederation of British Industry considers “very worrying”.

Should targets be used? This is hotly debated. The Davies Review called for FTSE 100 boards to achieve a minimum female representation of 25 per cent by 2015. He advised that should his recommended targets not be met by voluntary action, then government-imposed quotas could follow. The quota approach is either being considered or used in Norway, France, Spain and Finland. The reaction from British business groups has been unfavourable: the Institute of Directors called quotas “demeaning to women” and the CBI said quotas would be “bad for business”. The theme, therefore, is for UK firms to take the initiative and to act in their own self-interest in hiring more women.

Davies acknowledged that hitting 25 per cent is a tough target, so he included other useful suggestions: companies ought to disclose information in the annual report concerning the way they address diversity, including a description of search and nominations processes; and they should reveal diversity statistics. The executive search industry committed to playing its part in driving progress. Odgers Berndtson contributed to drawing up the industry’s voluntary code of practice. This covers succession planning over the medium term, the setting of diversity goals, defining the client brief to balance experience with relevant skills, the value of diverse long lists and support during the selection process.

The result should be a search process far more favourable to candidates from non-traditional backgrounds. Since only one board member in ten is female, it is absurd to require all new board members to have board experience, which would mean fishing only in the pre-existing – and narrowing – talent pool. Lift the restriction and a far deeper reservoir of talent is revealed, encompassing lawyers, professional advisers, accountants, strategy consultants and entrepreneurs, among others. All of these professions offers skills and experience which could prove invaluable on a board. Women are well represented among entrepreneurs and other start-up business leaders, and ethnic minorities are positively over-represented in this area.

Board diversity is more than mere biology, age or qualifications; it’s about finding the most potent mix of experience and personalities. One potentially rich untapped seam of talent for board roles is the world of entrepreneurs. You’ll find personalities who are comfortable with the daily challenge of business leadership, but who, by necessity, have controlled every other aspect of their companies too, from HR to finance. It will be hard to find similar candidates from the corporate world. And the mindset of the entrepreneur will bring something new to the table too. If you want to inject urgency and irreverence into your board, and want a director with a voice who won’t think twice about challenging assumptions, then an entrepreneur might be just what you need.

As Kester Scrope, chief executive of Odgers Berndtson, says: The intensity of competition, pace of change and complexity of international business now demand diverse perspectives on the board to engender innovation and understanding.”

The logic is compelling. What we need now is action.