Many organisations will find it necessary to adopt a growth culture over the years ahead or risk not being responsive enough to adapt to the change they are likely to face.

On the one hand, reinventing themselves will prove vital to attract the right talent. On the other, making the most of increased automation and artificial intelligence will require a cultural shift that, paradoxically, puts humans and their capabilities at the heart of the business.

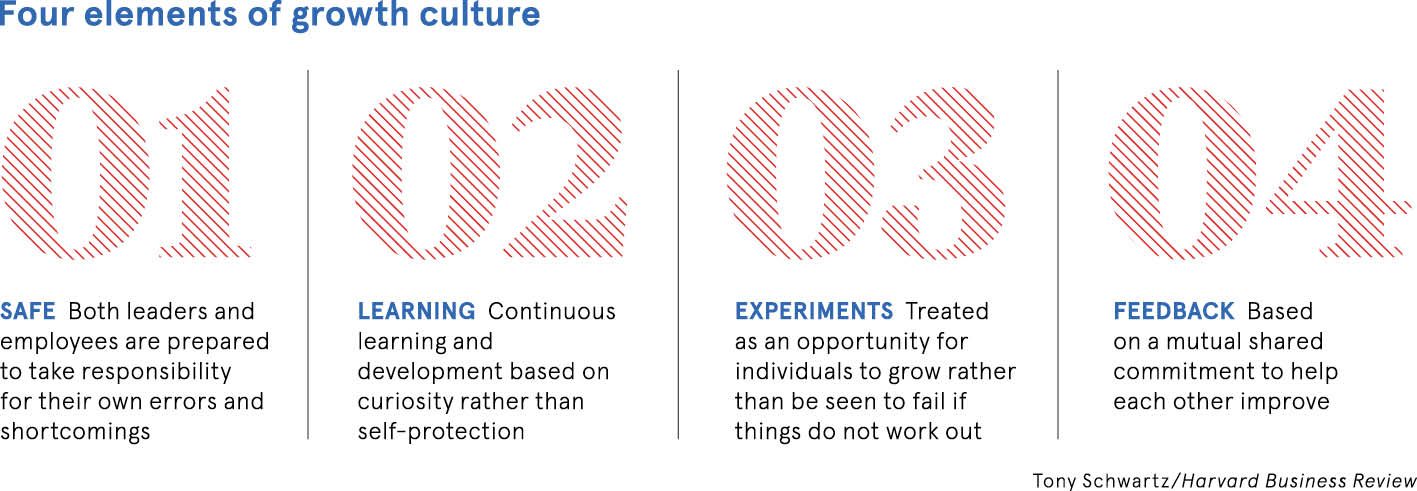

According to research published in the Harvard Business Review, a growth-based environment comprises four key elements. The first is a safe, rather than blame, culture, in which both leaders and employees are prepared to take responsibility for their own errors and shortcomings.

Next is a focus on continuous learning and development based on curiosity rather than self-protection. The third is a willingness to engage in experimentation, which is treated as an opportunity for individuals to grow rather than be seen to fail if things do not work out.

The final element involves encouraging continual feedback at all levels of the organisation based on a mutual shared commitment to help each other improve.

The most successful growth cultures are hybrid ones in that they still have some performance metrics, but they’re used only as a tool rather than the final measuring stick

A more traditional performance-driven culture, meanwhile, is one in which financial results matter more than individual growth and leaders tend to be autocratic rather than pragmatic.

But as James Beazley, chief executive of executive search and leadership advisory consultancy 6 Group, points out: “If you have a pure performance culture, the danger is you’re less agile as you’re so focused on hitting your numbers, irrespective of what your customers and the markets are telling you. So you might hit them this quarter, but it’s a big risk for the future.”

Perhaps surprisingly then, the number of companies that have introduced a growth culture is still relatively low. While particularly rare in heavily regulated industries, such as pharmaceuticals, they are more common in fields like manufacturing that are used to not dissimilar methodologies such as lean.

The approach is also coming to the fore among startups, especially in the technology space, which have been using comparable agile techniques for some time.

However, there are risks inherent in moving to a growth-based culture too. For instance, the average tenure of a UK chief executive has dropped from 8.3 years in 2010 to 4.8 years in 2017, according to PwC’s CEO Success Study. But this scenario presents problems should leaders wish to introduce cultural change, which can take a long time to bed in and show benefits.

“Growth cultures don’t necessarily translate into having your financial objectives met quickly,” says Mr Beazley “This means you really have to be quite strong to want to start driving a whole new approach that’s not purely focused on numbers.”

Another point to bear in mind, says Kirsta Anderson, a senior client partner at management consultancy Korn Ferry Hay Group, is when driving cultural change, the number-one success factor is for chief executives truly to believe their personal success depends on it, which most do not.

The second most important is that leaders are open to learning from feedback as well as being able to “demonstrate some level of vulnerability”, she says. But underpinning such behaviour in both instances is whether they have a fixed or growth mindset.

People with the former, who account for the majority, think of intelligence as a fixed trait that does not change over time. As a result, they are resistant to feedback, see it as a criticism and are threatened by the success of others.

People with a growth mindset, however, take the opposite approach. Because they believe their intelligence can develop, they embrace challenges as an opportunity to learn and are inspired by others’ achievements.

Ms Anderson explains: “Whether an organisation has a performance or growth culture depends on the mindset of their leaders. So when trying to bring about change, the key thing is to realise that your own underlying mindset can drive the wrong behaviour and results.”

One company that has taken a growth-based approach from the outset is startup Party Hard Travel, which organises clubbing holidays for 18 to 30 year olds, and took on its first staff in January 2016, of which there are now eight.

Each employee, once they have been hired, undertakes a Myers Briggs personality test. The aim is to discover more about them to help transition them into the job they are most suited to, even if it is not the role for which they were originally recruited.

In a bid to ensure a process of continuous improvement, co-founder Barry Moore also holds weekly one-to-one meetings with each staff member, who is asked five questions. They focus on one thing they love or loathe about working for the company, one thing they or the company could improve upon and one thing the company should start doing.

“It means we can find out about any problems early on and come up with new ways of doing things,” he says.

But if not managed carefully, the danger is that Mr Moore’s kind of open-door approach and willingness to discuss and review strategic decisions can result in a consensus-driven culture, where nothing ever happens, warns Mr Beazley.

“The risk is that you try to please everyone, but do nothing so there has to be a balance,” he says. “The most successful growth cultures are hybrid ones in that they still have some performance metrics, but they’re used only as a tool rather than the final measuring stick.”