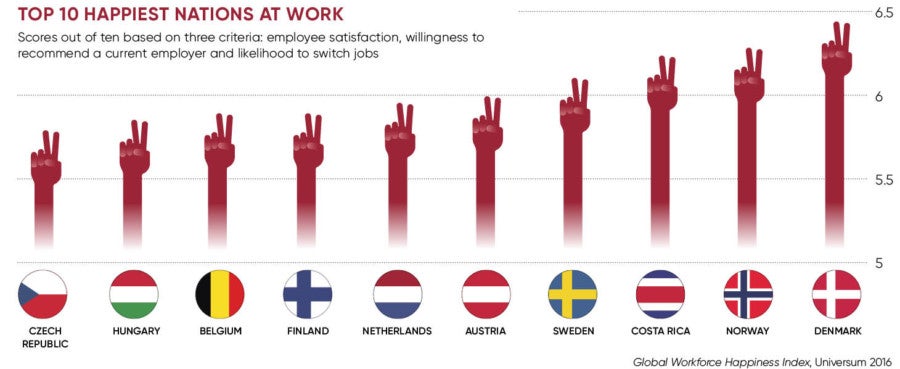

In 2016, Denmark grabbed the top spot in a global workforce happiness index by Universum. The survey of more than 200,000 young professionals in 57 markets used three criteria to determine employee happiness – employee satisfaction, an employee’s willingness to recommend a current employer and an employee’s likelihood to switch jobs in the near future.

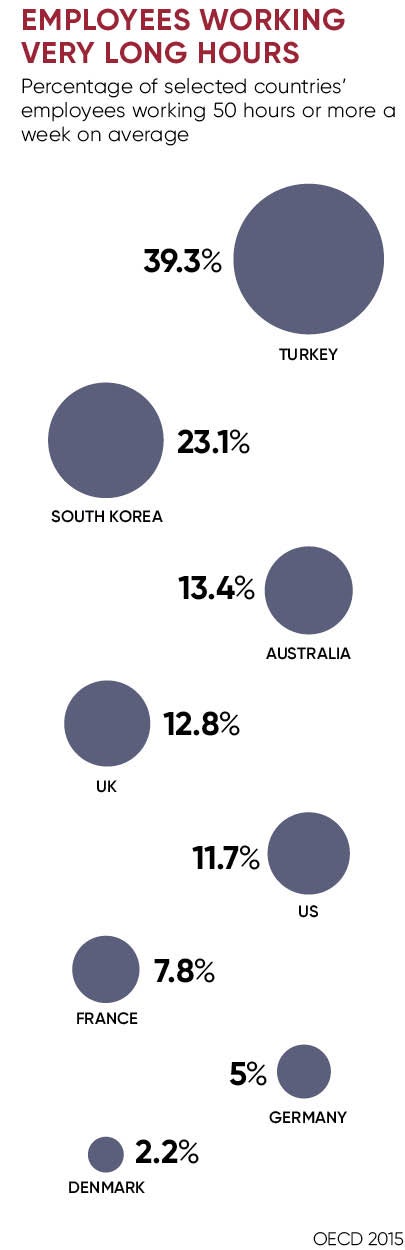

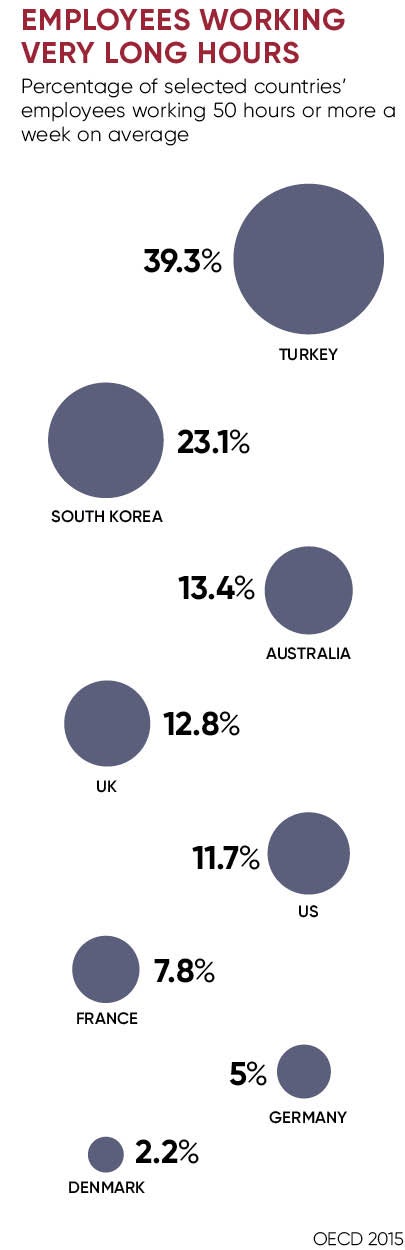

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Denmark has a better work-life balance than any other country surveyed. Only 2 per cent of employees regularly work very long hours, compared with the OECD average of 13 per cent. There is no national legislation in Denmark on the length of the working week, although the vast majority of collective agreements stipulate a 37-hour week. The Danes even have a word for workplace happiness: arbejdsgloede.

The UK could mimic aspects of Danish working life such as a more widespread adoption of a flexible working hours’ culture

Why is it important that employees are happy and engaged? Economists from the University of Warwick carried out a number of experiments to test the idea that happy employees work harder and found that happiness made people around 12 per cent more productive. “Talent wants to be in a place where they can be happy. Organisations want to make sure they attract that talent and retain them,” comments Jesper Dansholm, managing director, Denmark at Universum.

There are definitely cultural factors that contribute to the happiness of Danish workers, says Mr Dansholm. “We have a flatter organisational structure, and a high level of trust between owners and employees. With that level of trust comes the flexibility to get the work-life balance. People feel they are being respected by the company by being given a high level of flexibility in their working hours. There is also an informal atmosphere between bosses and employees.”

Statistics from Mercer-Sirota’s global engagement database reveal that 86 per cent of Danes trust their immediate manager, and recognise a spirit of co-operation and teamwork where they work.

Statistics from Mercer-Sirota’s global engagement database reveal that 86 per cent of Danes trust their immediate manager, and recognise a spirit of co-operation and teamwork where they work.

Denmark has a strong tripartite arrangement between unions, employers and the government, says Lesley Giles, director at The Work Foundation. “They have a high union membership in Denmark that influences the conditions of work. If you’ve got the conditions of ‘good work’ and support them socially and economically, then employees will be more committed and have the space to make a positive collaboration,” she says.

Historically, Denmark doesn’t have a strong industrial heritage, but it has a lot of medium-sized businesses, says Mr Dansholm. “This means that often the employee comes first. It’s easier to live by that phrase if you have a company with 50 employees and you know the reason you’ve grown by

20 per cent last year was due to your people. The individual contribution of the employee becomes very visible,” he says.

Dan Rogers, co-founder of software firm Peakon, which has its headquarters in Denmark’s capital Copenhagen, employs 50 people. He says: “There is a much stronger focus on work-life balance in Denmark. By nature of being a small company, we have a flatter organisational structure. In Denmark, they are very team focused and most Danish companies that I know of have a fixed lunchtime when everybody eats together. There is no barrier between the managers and their employees.”

Cary Cooper, professor of organisational psychology and health at Alliance Business School, believes Denmark does well in terms of employee happiness as they don’t have a long working hours’ culture. “The Danes also have very good salaries and are mostly in full-time employment,” he says.

Denmark has one of the strongest social security systems among OECD countries. “Flexicurity” is the Danish model for flexibility in the labour market and is essentially a blend of generous social security measures and an active labour market policy with rights and obligations for the unemployed. “It’s one of the best countries to be in terms of being made redundant. Your loss of earnings will be 2.3 per cent compared to an OECD average of 6.3 per cent,” says Professor Cooper.

He believes the UK could mimic aspects of Danish working life such as a more widespread adoption of a flexible working hours’ culture. “Do we need to work 40 hours a week? The Danes have had flexible working for a long time and for me work is not about having long working hours.”

UK organisations could flatten their hierarchical management structure, says Mr Dansholm. “This can be done in the UK, but it’s easier in Denmark as we have smaller companies and a smaller population. Organisations need to leave the ‘old school’ management style and trust employees to deliver their goals,” he says.

Workplaces in the UK need a paradigm shift that re-envisions the world of work, argues Jenna Kerns, research and policy assistant at The Work Foundation. “This should include a recasting of what a healthy, good work-life balance is, and a balance that not only benefits the employee, but ultimately benefits the employer as well and has a positive knock-on effect on their bottom line.”