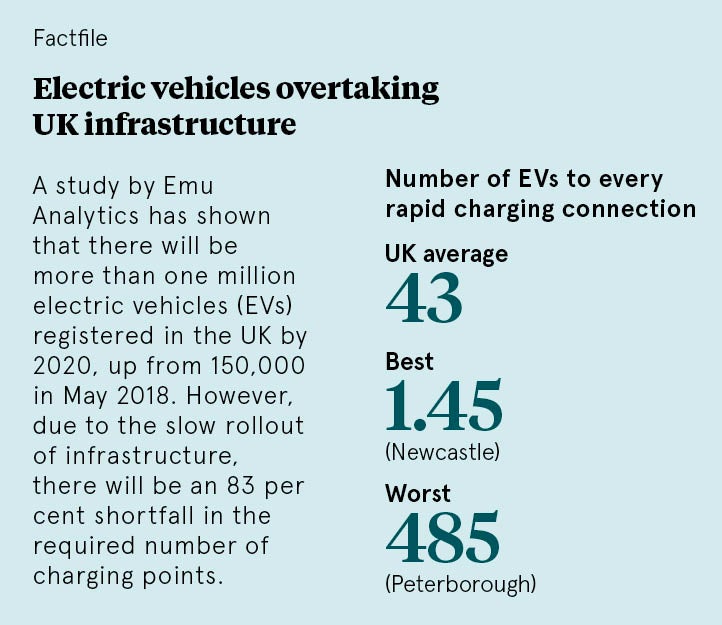

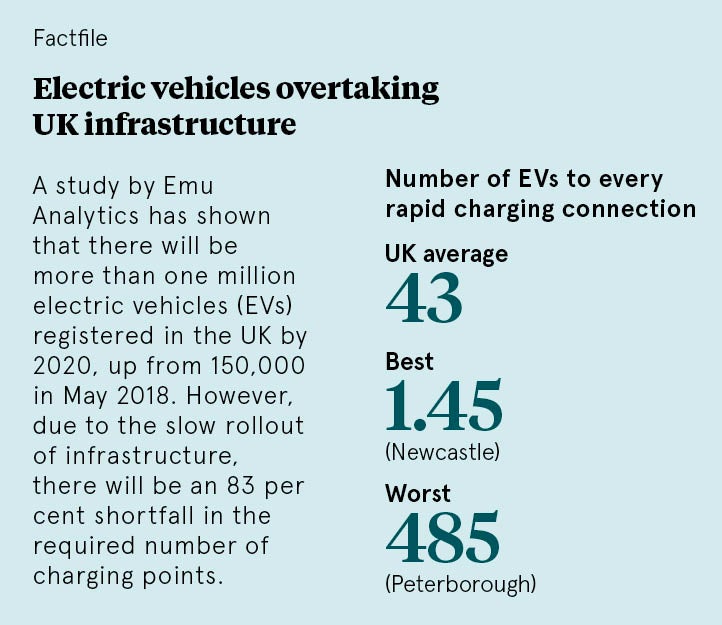

Electric vehicles currently make up just 4.3 per cent of new vehicle registrations nationally. But the UK is seen as a European centre for electric vehicles because of government incentives for carmakers to invest in production capacity. However, a lack of costly infrastructure has held back development.

According to the National Infrastructure Commission, battery power could save the UK £8 billion a year by 2030 as electrification is estimated to reduce energy usage by around 50 per cent, making everything much cheaper to run.

As well as economic benefits, going electric on the roads improves UK energy security through the reduction in reliance on oil and dependence on oil-producing nations.

Electrification promises to reduce congestion, dramatically cut road traffic accidents and bring mobility to the immobile

Air pollution is major reason for switch to electric vehicles

While reductions in operational costs and pollution are the obvious benefits of electrification, electric transport is also set to underpin the autonomy revolution as the UK seeks a lead in the fourth industrial revolution and, in particular, self-driving vehicles.

“When compounded with autonomy, electrification promises to reduce congestion, dramatically cut road traffic accidents and bring mobility to the immobile,” says Robert Harwood, global industry director at engineering simulation firm ANSYS.

Exciting though this may sound, environmental factors are primarily driving the government’s policy decisions in this area. Diesel buses are around four times more polluting than private cars. With the clean air zones being introduced in a number of UK cities, and motorists deterred by congestion and parking costs, the need for an efficient and clean bus service is greater than ever.

“Air pollution is the greatest health problem after obesity in the UK,” says Matthew Pencharz, a former deputy major of London and now non-executive director for Off Grid Energy. Indeed, poor air quality results in around 40,000 deaths every year, 9,000 of which are in London. “Electrifying transport reduces harmful tailpipe emissions and carbon emissions,” Mr Pencharz adds. “The UK already has a low and decreasing grid carbon intensity, and there is broad support across government.”

Electric vehicles already have a jump-start in the UK with buses

Growth in electricity consumption is increasing rapidly and will double by 2050, according to DNV GL’s Energy Transition Outlook. This is driven by significant electrification of energy demand in all regions and sectors, particularly electric vehicles.

Road transport dominates transportation energy use and DNV GL predicts that by 2027 all new cars sold in Europe will be electric vehicles. Recent advances in heavy vehicle electrification are leading to swift uptake of battery power for public buses too and is expected to reach 80 per cent just after 2030 in Europe.

The UK has the most electric buses in Europe. Hybrid electric buses currently run in numerous British cities, representing 18 per cent of Europe’s entire fleet, though the adoption is dwarfed by China which operates more than 98 per cent of the global total.

“The electrification of UK road transport is still in its infancy, though political will and falling costs are starting to drive a transition,” says Laurence Chittock, senior transport modeller at Mott MacDonald. “The cost of an electric bus, which traditionally is much higher than a diesel equivalent, is falling rapidly.

“Thorough planning is required to identify suitable services and integrate a charging regime. Transport for London is currently embarking on a transition to electric buses by identifying where this can be implemented, such as on the European Union-funded ELIPTIC project.”

Electric railways lagging behind

Electrification of the UK’s railways, however, lags behind most of Europe. Only 42 per cent of the UK’s rail network has been electrified, compared with 76 per cent in the Netherlands, 71 per cent in Italy and 61 per cent in Spain, according to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.

While several major electrification schemes were initiated, including Cardiff to Swansea, Kettering to Sheffield and Windermere to Oxenholme, they were cancelled by the government last year due to growing infrastructure costs.

“Rail electrification will continue, but remains a small sub-sector,” says Ditlev Engel, chief executive of DNV GL Energy. Meanwhile, the electrification of air travel will still be in its infancy by 2050, he adds.

Use of smart systems required to cope with new energy demands

Electrifying UK transport services en masse means more electrical energy will be required from the National Grid, on top of the anticipated demand from domestic electric vehicles leading to a huge change in capacity and load profile demands.

Although the grid has the capacity to meet the predicted demands, higher uptake of electric vehicles in certain regions, combined with a lack of infrastructure investment, has the potential to cause significant local challenges, including possible reductions in voltage.

“To minimise the need for reinforcement of our ageing electricity infrastructure, we need to see fully flexible charging and smart systems that communicate with the wider energy system in real time, to help us gain a wider understanding of the optimal time to charge and minimise new peak demands,” says Chris Evans, deputy managing director at engineering consultancy Rolton Group. “This has been stated as the route by government.”

In the coming years, the government’s strong policy stance on the electrification of road-based transport will significantly accelerate public transport services in this area. However, the large investments required in the rail network, to ensure the UK keeps up with electrification in other parts of the world, for now appear unlikely.

Air pollution is major reason for switch to electric vehicles

Electric vehicles already have a jump-start in the UK with buses