Forget your fondness for Don Draper’s Mad Men suits and your nostalgia for classic 30-second TV ads, Google and Facebook are swallowing advertising whole.

The digital duopoly’s dominance of an industry with more than 150 years of history has been achieved inside a generation.

Google and Facebook so big that they are squeezing competitors out

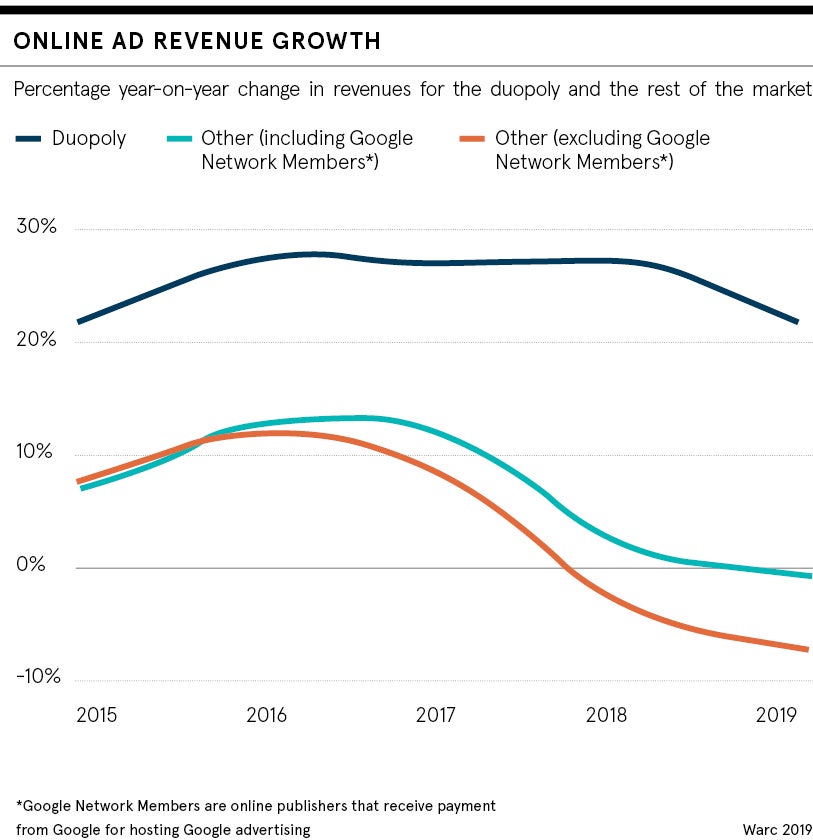

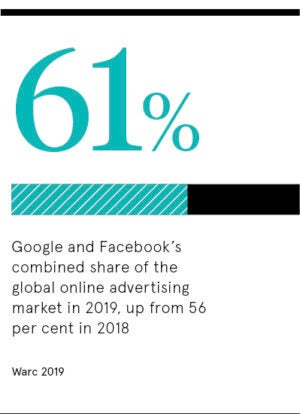

Predictions from industry analyst WARC in its Global Advertising Trends Report, released last month, suggest that Google and Facebook’s share of the global online ad market will grow to 61.4 per cent this year, up from 56.4 per cent in 2018. The duopoly’s $176.4 billion in forecasted ad revenues amounts to a 22 per cent increase on 2018. For everyone else, the future looks tough as internet advertising spend outside the duopoly is predicted to fall by 7.2 per cent.

The platforms want yet more of the pie, encroaching into specialist areas of advertising. Facebook last month announced Facebook Showcase, a programme to sell ad spots for its Facebook Watch video service. The strategy mirrors the broadcasting sector’s use of “upfronts” to sell ads for hit TV shows. Facebook has an in-house Creative Shop that works with brands across its portfolio, which also includes Instagram, Messenger and Oculus. Google has its in-house creative team, Google Zoo, to assist brands in making the best use of YouTube and its other technologies.

The platforms want yet more of the pie, encroaching into specialist areas of advertising. Facebook last month announced Facebook Showcase, a programme to sell ad spots for its Facebook Watch video service. The strategy mirrors the broadcasting sector’s use of “upfronts” to sell ads for hit TV shows. Facebook has an in-house Creative Shop that works with brands across its portfolio, which also includes Instagram, Messenger and Oculus. Google has its in-house creative team, Google Zoo, to assist brands in making the best use of YouTube and its other technologies.

The rest of advertising is being squeezed for money and talent, particularly the adtech companies, which match advertisers with online audiences, but don’t have access to the vast data pools accumulated by the duopoly.

“The big tech giants hold a huge amount of data on consumers, but with great power comes great responsibility,” says Ruth Manielevitch, vice president of global business development at mobile ad technology company Taptica. “The industry needs an independent regulatory watchdog that would serve to scrutinise the powers of the big tech giants, diminish the monopoly they have and demand greater transparency, which would build trust among consumers.”

Google and Facebook succeeded because they offered convenience

The US Federal Trade Commission has announced a task force to investigate anti-competitive conduct in the tech sector. A UK parliamentary committee last month called for Facebook to be subject to statutory regulation and branded the company “digital gangsters”.

Stewart Easterbrook, chairman of data-driven media agency MiQ and former chief executive of Starcom MediaVest, explains the duopoly’s ascendancy as a matter of convenience. “Over recent years clients and [media] agencies have arguably become too reliant on the easy scale that Facebook and Google have provided them,” he says. “It’s a friction-free way of communicating to very large audiences.”

But platforms have a vested interest when advising brands, he argues, and media agencies must demonstrate their independence so clients trust them “to ensure that their money is distributed appropriately to reach the right customers”, says Mr Easterbrook.

Such is the imbalance in data that Eric Visser, chief executive at Dutch-based ad marketplace JustPremium, calls for drastic measures. “The whole ecosystem, outside Google and Facebook, should collaborate on collecting data and making it widely available to anybody else,” he says. “As long as we keep feeding the cookie monsters – Google and Facebook – we are not going to get there.”

Mr Visser claims there are limitations to the ad templates offered by Facebook’s Creative Hub tool and Google, which clients should recognise. “If you want to stand out, you need a bigger canvas,” he says. “Creativity is most essential in the success of a campaign.”

Could news brands collaborate to take on the duopoly?

Digital news publishers have been especially hard hit by the duopoly. Tracy De Groose, executive chair of Newsworks, the marketing body for UK newspapers, points to Planning for Profit, a study of advertising return on investment across multiple categories, showing that £3 billion was “left on the table” by advertisers who ignored news brands in campaigns. “News brands have been under-invested in mainly because digital platforms have been over-invested in,” she says.

Ms De Groose, former UK chief executive of Dentsu Aegis Network, wants publishers to be allowed to join forces and compete with the duopoly, citing the Ozone Project, an advertising network created by four UK news organisations. “I’m not sure there is fair competition,” she says of the unregulated tech giants. “We have to adhere to the regulation in our sectors and be cognisant of the competition authorities in a way that I don’t think tech giants are.”

Mazen Hussain, director of paid media and creative at digital marketing agency Croud, argues that clients still have many alternatives to the duopoly, highlighting the strengths of Pinterest, Chinese-owned video app TikTok and the live-streaming video platform Twitch, owned by that other tech giant Amazon, which could make $11 billion in US ad revenues this year, according to eMarketer.

Celine Saturnino, chief commercial officer at behavioural media agency Total Media, highlights the advertising potential Amazon has in voice-activated media and notes that podcasts are surging in popularity. “That’s a huge opportunity and one that has been largely untapped,” she says.

The duopoly is not guaranteed to rule forever. Ms Saturnino concludes: “Facebook currently has a huge proportion of inventory and total audiences, but they will definitely be challenged by the next big thing; among the younger generation, it’s not seen as a cool, hip and trendy platform to be on.”

Google and Facebook so big that they are squeezing competitors out

Google and Facebook succeeded because they offered convenience