Like mighty armies in the kind of lavishly produced box-set period drama viewers love to binge on, great over-the-top (OTT) services are drawing up their battle lines.

Apple+, Disney+ and BritBox have recently taken the field, manoeuvring for position against rival combatants Amazon Prime, YouTube and Hulu. Netflix already holds the upper ground. Soon, HBO Max and Peacock will belatedly appear on the horizon, like the Prussians at Waterloo.

These streaming wars are real and of historic cultural and economic importance. Billions of dollars are at stake, along with the fate of many of the great names in global entertainment.

For consumers, who will ultimately decide the outcome, the impending fight will be a grand spectacle that promises them the spoils of ever-greater choice of hyper-personalised original content, unimaginable in times before disruptive technology altered the course of visual media.

“UK becomes a nation of streamers”, declared UK media regulator Ofcom this summer as it reported the number of households signed to OTT services grew from 11.2 million (39 per cent) in 2018 to 13.3 million (47 per cent) in 2019.

Grabyo, the online video production group, found in its annual Global Video Trends report that OTT services now dominate over pay-TV services in the United States, Europe and Australia. It identified Netflix as the global market leader in subscription-based video on demand (SVOD) with 54 per cent market penetration, rising to 61 per cent in mainly English-speaking countries.

But Netflix has recently faltered. Its share price fell this year over disappointing subscriber numbers and the perceived threat from newly arriving OTT services, which are pulling their original content from Netflix’s platform.

Subscription-based streaming bubble going to burst

Mark Harrison, managing director of the DPP, an international business network for the media industry, says so much visual media is being created he foresees a “content bubble”, comparable to the dot-com bubble generated by wild investment in tech stocks 20 years ago.

“Not many people are actually making any money from this,” he points out. “The supply of content is going up and up and up in response to a demand that is huge but really poorly understood and a funding model that is failing to deliver. There will be a point at which something bursts. The question is what provokes that and what comes next.”

OTT services will form alliances to survive. “We may see even more mergers and acquisitions, companies flying into each other, restructures,” Mr Harrison predicts.

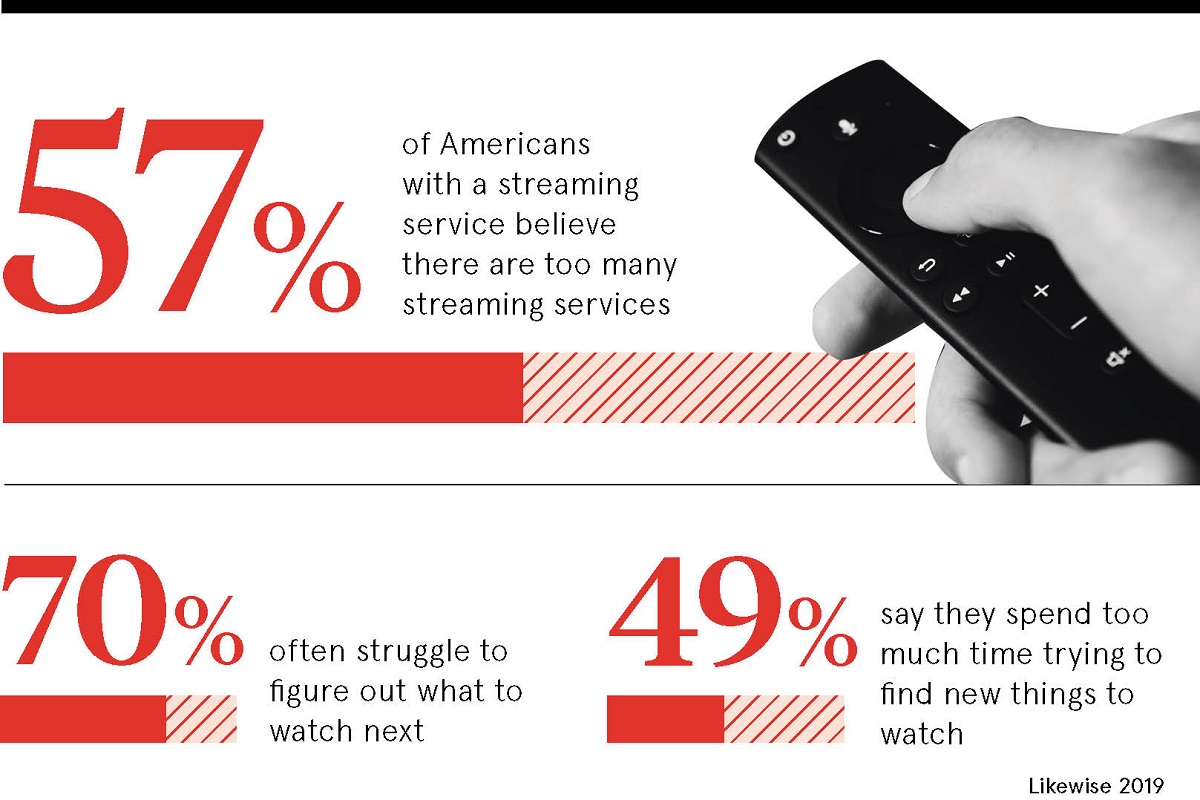

Content exists in abundance, but audience dissatisfaction remains, he says. When the bubble bursts, the companies who listen to what consumers complain about will be the ones left standing. “People are frustrated that it’s so hard to find what they want to watch and, if they were able to watch everything they would like, it would require them to subscribe to a huge number of services,” he says.

Two classes of video consumer will emerge. “We are going to see content subscription as an indicator of wealth; if you are affluent, you will subscribe to a huge range,” says Mr Harrison. “The subscription ‘have-nots’ will have a lot of content services that are advertising-driven and free to use.”

Disruptive innovation in on demand just starting

Graham Field, head of programmatic at MediaCom, foresees a surge back of ad-funded “freemium” streaming as the race for quality content inside so-called walled-garden OTT services causes some players to drop out and leads to price inflation. Platforms such as ITV Hub and All4 can already attract “massive” audiences for culturally significant shows, he says.

“A lot of that consumption is happening on mobile; individual viewing of shows that people engage with and like the ad-funded model, provided the quality and value exchange is there,” says Mr Field. But he warns such services against over use of hyper-personalised ads, which can cross “a creepy line”.

Digital content delivery service Limelight Networks produces an annual State of Online Video report that identified cost as the “primary concern” of UK SVOD subscribers, with 54.6 per cent saying they would cancel a subscription if it became too expensive.

Quality of the streaming itself will also determine who wins when the streaming bubble bursts. Michael Milligan, senior director at Limelight Networks, says “Twenty-six per cent will stop watching a video the first time it buffers. The second time, it goes up to above 60 per cent.”

While the arrival of 5G will bring sufficient bandwidth to “make your mobile device pretty much HD or UHD quality from just about any screen anywhere”, OTT services must exploit disruptive tech to reduce delay in delivery of live events, says Mr Milligan.

“You might get a tweet of something that happened before you have seen it online,” he says. “So we are seeing more low-latency live streaming, instead of being delayed 30 to 40 seconds it can be as low as three to four seconds.”

A ‘Spotify’ of OTT content

Eventually, DPP’s Mr Harrison believes, video on demand will fall in line with music and offer consumers all content in one place, like a Spotify or iTunes. “You have global players in this space who have the technology and money to provide aggregated platforms. And you have high-quality content providers that are starting to suffer because they can’t get the revenues to support their catalogue,” he says.

“I am not saying it will be Apple that does it, but if you look at what they are doing around aggregating news, aggregating music, they have a track record. When iTunes began, it had lots of great music, but not everything; it couldn’t get The Beatles on iTunes for ages. It happened because it’s what consumers want. Ultimately, consumers get what they want.”