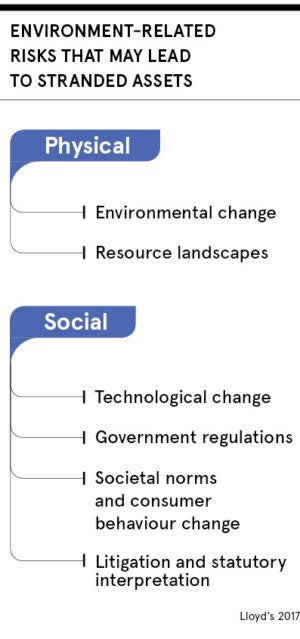

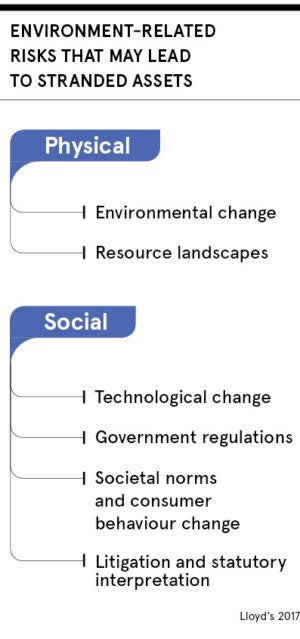

Owning stakes in major energy assets, such as oil fields, coal plants or gas pipelines, is typically a hugely expensive, long-term investment. It’s a commitment that has historically paid off for both energy companies and their backers, who have collectively reaped the profits from decades of exponential leaps in global energy consumption. But what happens when those assets become a growing liability, as policies shift towards curbing fossil fuels, rather than supporting them? This is when stranded assets can become an issue.

When investing in rail, you now need to look at energy policy and ask whether those tracks are still going to be needed in 20 years

A stranded asset – one that experiences an early write-down in its valuation or becomes obsolete – represents a significant risk to the balance sheets of companies invested in the energy sector.

The Paris Agreement saw 185 states commit to cull carbon emissions progressively from 2020, which sets a rising cost to owning assets that emit high levels of carbon. The International Energy Agency has warned that $1.3 trillion of oil and gas assets could be left stranded by 2050, if the fossil fuel industry does not adapt to greener climate policies. But is the growing risk of stranded assets being reflected in investors’ behaviour and in the value of their investments?

Are investors more worried about stranded assets or damaged reputations?

Alex Harrison, a partner specialising in energy policy at law firm Hogan Lovells, believes that investors are more worried about the reputational damage of being associated with fossil fuels than the risk of their investments becoming stranded. “My sense is that the threat of a physical or legal prohibition on being able to exploit their reserves isn’t chief in investors’ minds,” he says. “Their bigger concern seems to be the threat to their social licence to operate that comes from being active in the fossil fuel sector.”

But Giuseppe Corona, who manages global investor AMP Capital’s $284-million Global Listed Infrastructure Fund, says far from just being an image problem, shifts are already happening in the perceived value of fossil fuel-based assets. “I can see changes in the equity markets. The cost of capital for assets at risk of being stranded is getting higher,” he says. Lenders are requiring a higher level of returns on assets at risk of being stranded in the mid to long term.

Mr Corona says: “Coal assets are most at risk of becoming stranded. Oil assets are probably second in line. Gas is the one that is tricky; of all the conventional energy sources, it’s possibly the cleanest.”

The wide-reaching impact of coal spending clampdowns

The wide-reaching impact of coal spending clampdowns

When it comes to predicting which energy assets are in especially high danger of being written off or devalued, it is also a question of geography. Mr Corona’s fund managers have to make an assessment on a country-by-country basis. He says: “The United States, for example, has seen a lot of coal being decommissioned. In China, too, policy is switching from coal to gas. So the impact of decarbonisation on coal investments in those countries is already undeniable. But with significant investment in gas, the risk of stranded gas assets is probably very far down the road.”

Clampdowns on spending in the coal industry have also produced a knock-on effect of creating stranded assets in other sectors. Policies designed to avert climate change have led to stranded assets in transportation, such as rail tracks which were dedicated to taking coal to power plants. “When investing in rail, you now need to look at energy policy and ask whether those tracks are still going to be needed in 20 years,” says Mr Corona.

Investors must, therefore, juggle multiple timelines when assessing which assets in their portfolios could become stranded. “By our estimation, it’s a multi-decade process,” he says. “For example, oil demand is rising in developing countries. Therefore, the chance of stranded assets in the oil sector is more likely from 2030 onwards.”

$1.3 trillion of oil and gas assets could be left stranded by 2050 if the fossil fuel industry does not adapt to greener climate policies

Vital thing for investors is being ahead of the anti-carbon curve

Mr Harrison agrees that in the long term it will be the oil majors which own as-yet untapped reserves that could face the most risk of obsolete assets. “The most exposure to risk is going be on the balance sheets of the majors,” he says. “There seems to be a recognition of fundamental inconsistency between decarbonising and exploiting those reserves. However, I don’t think we’ve yet reached the point where anyone is thinking they are going to have to leave assets in the ground.”

Mr Corona says whether an investor in the energy sector is an oil and gas giant, an activist shareholder or a major fund such as his own, being able to predict and outpace the rapid technological, political and social evolution regarding carbon is now one of the biggest challenges. He concludes: “The tricky part of our job is that we deal in very long-term assets. For the investment to work, you need to be able to rely on long-term cash flows. But things are changing so fast.”

Are investors more worried about stranded assets or damaged reputations?

The wide-reaching impact of coal spending clampdowns

The wide-reaching impact of coal spending clampdowns