With the help of parallel text datasets such as Wikipedia, European Parliament proceedings and telephone transcripts from South Asia, machine-learning has now reached the point where translation tools rival their human counterparts.

According to Ofer Shoshan, chief executive of One Hour Translation, neural machine technology (NMT) translators will be capable of handling 50 per cent of the global translation market in one to three years.

In another ten to twelve years, machine-translation technology will achieve human parity and then eventually surpass it

NMT translators might not be mainstream yet, but the biggest companies in the world, including Google, Microsoft and Amazon, are engaged in a fascinating race to close the communication gap between their software and skilled translation workers and agencies.

AI translation has flourished most in business

Business has been a key use-case from the start as technology giants position their Skype tools, translation apps and smart speaker skills as essential to any companies looking to expand in foreign markets.

Wearable tech startups too are still able to make an impact with Waverly Labs’ Pilot, Timekettle’s WT2 and Mymanu’s Clik+ all vying for the space left open by last year’s Google Pixel Buds, which were criticised as being badly designed and too reliant on connected Android smartphones. Actions like interacting with Alexa or popping in a smart earbud can make much more sense in a client meeting than for an everyday tourist.

This has led industries, including hospitality, retail and law enforcement, to experiment with artificial intelligence (AI) translation, with usage in the medical and financial sectors also expected to grow as translation is fine-tuned for these specialised areas.

“In ten to twelve years, we’ve progressed from no access to machine translation to today’s standard of AI translators, which aren’t perfect but are pretty good in most cases,” says Andrew Ochoa, founder and chief executive of New York startup Waverly Labs. “It’s not difficult to see that in another ten to twelve years, machine-translation technology will achieve human parity and then eventually surpass it.”

Simultaneous translation is the next development on the horizon

A development Mr Ochoa expects to see in the next phase of AI translation engines is a shift from phrase-based speech translation to simultaneous translation, something of a Holy Grail in the industry.

From the results of early demos of the WT2 in-ear translator, which is expected to be able to perform real-time translation face to face around the time it ships in January, it looks like there will be a trade-off between speed and accuracy, at least for 2019 and the few years following. Still, this technology moves quickly.

For virtual communication, meanwhile, real-time transcription and translation services via Skype’s Meeting Broadcast, part of Skype for Business Online and Office 365, are already live in public preview. The feature is available in ten out of sixty languages offered by Microsoft Translator. Google Translate is still the most global option. It operates in more than 100 languages, with 32 in voice or conversation mode and 40-plus with visual translation. While Pixel Buds didn’t take off, in October Google made Translate compatible with any assistant-optimised headphones.

AI translators still miss emotional and cultural aspects of language

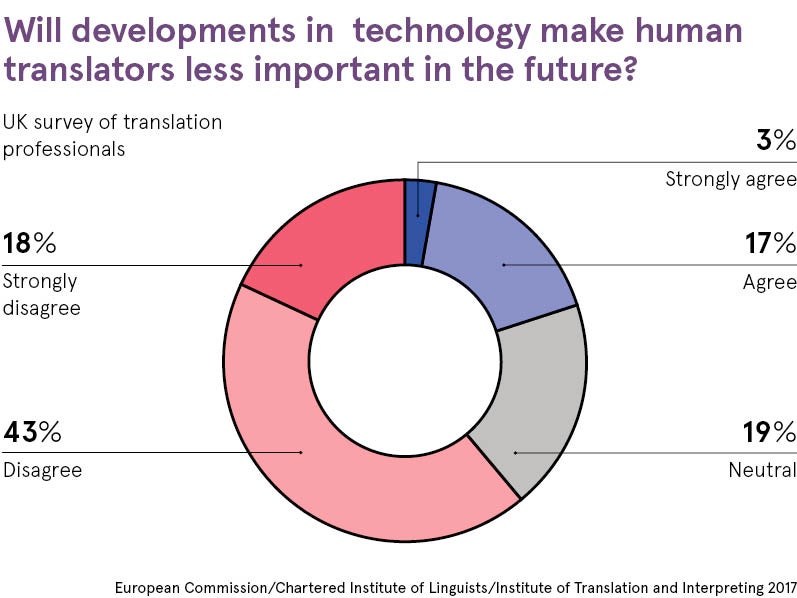

As the technology becomes more intelligent and errors decrease during the next decade, some important limitations will remain in place. That’s why some experts believe people will always have a part to play when it comes to translation and language at work.

Dr Catherine Hua Xiang, programme director of Chinese language and culture for business at the London School of Economics, says there are three reasons for this: the meaning of language is always context based; language is closely related to human emotions, so the subtlety of tones and voices change the impact and meaning; and language can’t be separated from culture.

“In a guest-host relationship in a Chinese business setting, for example, it is considered polite and necessary to insist and impose on guests to accept the invitation or have more food,” she says. “This is considered essential to show sincerity and hospitality. Chinese people will use the imperative form, such as ‘You must come’ as an invite, or ‘Eat, eat, eat’ or ‘Eat more, you are not eating enough’, during the actual business meal. Despite the fact it may sound like orders, it is absolutely not in this particular context.”

Cultural transfer is a challenge for any translation work, according to Dr Xiang, who believes that many businesses are not fully aware of the influence of cultural understanding in their approach to business.

Disparity in data means some languages better served than others

Other obstacles for AI translators are the languages themselves. European languages tend to be the best served by these types of tools, alongside Chinese and Japanese, but predictions for parity within ten years will probably only apply to parallel languages with plenty of readily available datasets. “Low resource languages, such as Haitian or Amharic,” says Mr Ochoa, “are going to struggle without dedicated resources made available to include these languages in new models.”

Even as AI translators are introduced into business settings, human translators can provide value not only in terms of context, emotional intelligence and culture, but also working alongside NMT to check and correct text translations in an agency workflow, for instance. Mr Ochoa also points to a potential collaboration in that human translators experience fatigue, becoming less accurate over long sessions, whereas an AI tool may start off less accurate and improve over the course of the meeting or transcription.

It seems likely that human translators will remain valuable to businesses even if NMT translators match them on accuracy and performance within the decade. “To communicate effectively with potential business partners, clients and customers, businesses need to know what to communicate and how to communicate,” says Dr Xiang. “This is where cultural knowledge and awareness makes a difference. Different cultures have different approaches when it comes to communication. Building such understanding of how a particular culture communicates and its core values will help build rapport and win more business.”

AI translation has flourished most in business

Simultaneous translation is the next development on the horizon

AI translators still miss emotional and cultural aspects of language