As fears grow over a looming trade war between the United States and China, American manufacturers are already experiencing the cost of protectionism.

CP Industries, which makes steel cylinders for the US Navy and Nasa, has revealed new tariffs could add more than $0.5 million to raw material costs over the next six months. “How long can we last?” asks Michael Larsen, the company’s chief executive. “We could go down relatively fast.”

CP Industries, which makes steel cylinders for the US Navy and Nasa, has revealed new tariffs could add more than $0.5 million to raw material costs over the next six months. “How long can we last?” asks Michael Larsen, the company’s chief executive. “We could go down relatively fast.”

President Donald Trump’s recent tariff announcements seek to impose a 25 per cent penalty on steel imports and 10 per cent on aluminium imports from China. The tariffs are designed to fulfil the president’s 2016 campaign promise to protect the US steel industry while returning jobs to Rust Belt communities.

US President Donald Trump holding the Section 232 Proclamation on steel imports

But as US and Chinese rhetoric over trade has intensified, taxes on hundreds of additional agricultural and industrial goods have been announced by both countries. Within 24 hours of the White House unveiling an additional list of 1,333 Chinese products also subject to tariffs of 25 per cent, Beijing responded in kind with a list of 128 US products, including exports such as cars, aircraft, soya beans, dried fruit and nuts, modified ethanol, pork and wine.

A list, published by China’s Ministry of Commerce, shows 120 American products will be subject to an extra 15 per cent tariff, while seven different types of pork products and aluminium scrap will carry a 25 per cent hike. The value of US exports to China subject to raised tariffs amounts to nearly $3 billion, according to the ministry.

China has carefully targeted US exports from swing states with powerful lobbies in Washington

In America, the tariffs have been welcomed by the steel industry, which employs 140,000 people and has long campaigned for a reduction in imports from China. According to the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI), an association of producers, China sent 800,000 tonnes of steel into the US in 2017; in return, 96,000 tonnes of steel were exported from America to China. The AISI says only 0.1 per cent of all US steel exports went to China.

According to Thomas J. Gibson, AISI president and chief executive: “We are grateful to the president for his continued commitment to the steel industry and to ensuring the country’s national security interests are defended by combating the flood of imports that have been eroding America’s steel industry over the past several decades.”

But according to figures released by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, increased tariffs on American steel could have an outsized effect on another 5.4 million workers employed in a host of other industries which rely on steel, such as car manufacturing and construction. A study by the Council on Foreign Relations shows that higher prices for imported steel could lead to a 4 per cent drop in car sales and jeopardise as many as 45,000 jobs in the US car industry.

Another consequence of tariffs on steel can be traced to employment in those industries which use a lot of steel, such as building fabrication. “We have seen these tariffs impact the cost dynamics of the steel supply chain, but it’s important to remember that there is a lot of steel in almost every type of construction project,” says Brian Raff, director of government relations with the American Institute of Steel Construction.

“In fact, there is nearly 80 per cent of the amount of steel in a concrete-framed building as there is a steel-framed building due to the density of steel reinforcing bar required, so construction costs will impact concrete buildings similarly.”

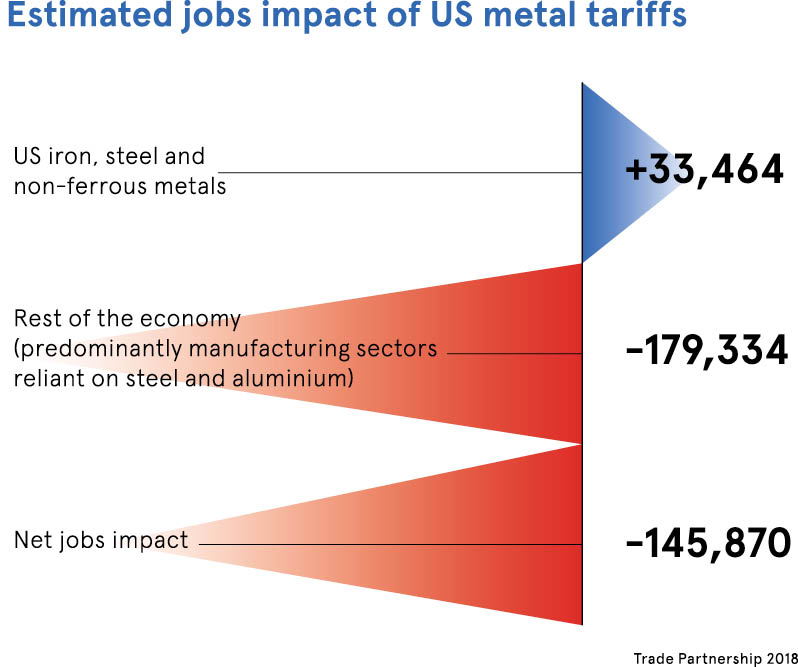

Mr Raff points to a study conducted by The Trade Partnership, a consulting group which researches the impact of trade policies. It shows that while tariffs would increase employment in the iron and steel industries by 33,464 jobs, they would also cost up to 179,334 jobs in other sectors throughout the economy – a net loss of almost 146,000 US jobs.

“For the Chinese, the reason for replying to US tariffs is very simple; they are increasingly expanding international trade,” explains Dr Ulrich Volz, head of department and senior lecturer in economics at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies. “I think there is a high chance that the range of products affected will expand. In the US, there are already companies which have been directly affected – companies importing aluminium. That will have a negative impact on the US economy.”

While Trump appointees such as commerce secretary Wilbur Ross have played down the prospect of a trade war, and other officials have indicated the proposed tariffs are meant to signpost a new round of tough trade negotiations, analysts say US farming is also vulnerable to tariff hikes. For example, China is the largest consumer of American soybeans, which are largely produced in Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota. China buys around 61 per cent of American soybean exports.

The concerns of soy farmers have also been echoed by car manufacturers and aviation firms. China imports nearly 270,000 American vehicles each year, worth $11 billion. US imports of Chinese cars are negligible. Ford alone ships about 80,000 vehicles a year to China. The American aviation sector, worth $13.2 billion in exports to China in 2016, has also urged both countries to resolve their differences amicably.

China analysts think Beijing would ultimately benefit from a protracted trade dispute. “I think the conversation in China is muted because President Xi Jinping has consolidated power and policies emerge from whatever the state wants,” says Ann Lee, author of What The US Can Learn from China and Will China’s Economy Collapse? “I think there would have been a more intense debate before, but now that Xi has consolidated power, the Chinese are trying to come across as more united.”

Ms Lee says China has carefully targeted US exports from swing states with powerful lobbies in Washington. “The steel and agriculture lobby is very powerful, and Boeing has a strong voice as well. So the Chinese have targeted where it could hurt most, in poorer states. I think this was a calculated decision with a view on Rust Belt states in the mid-terms. Affecting jobs there is where the Chinese feel they might have most leverage with President Trump,” she concludes.