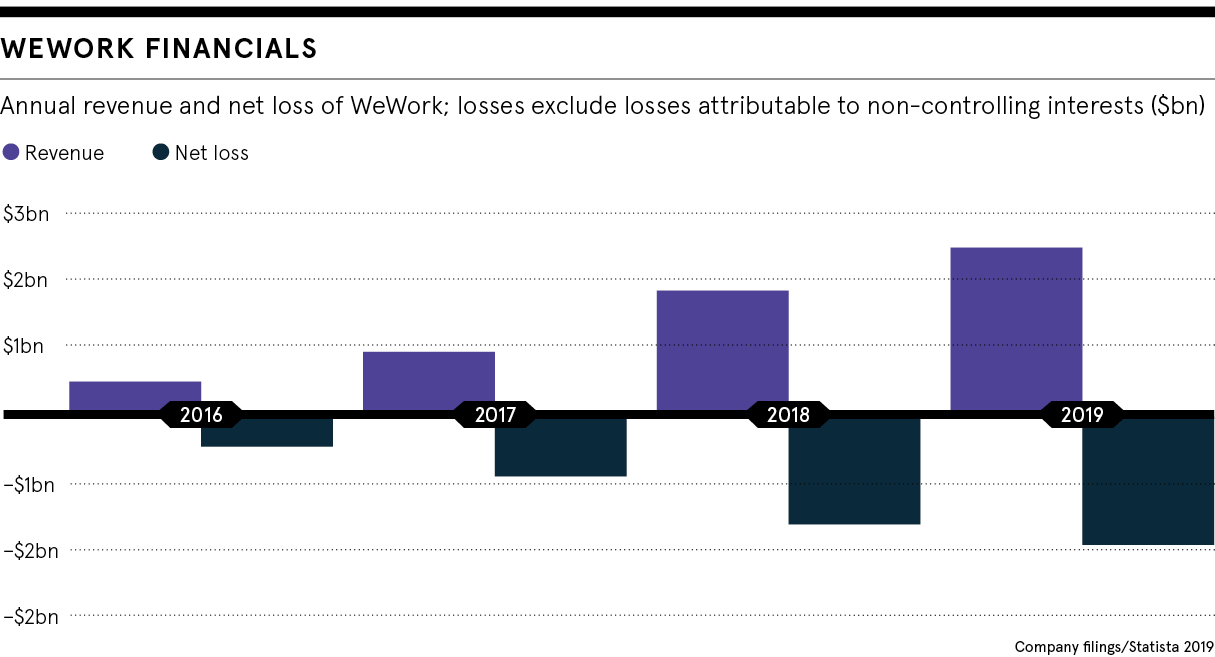

In early-2019, even though it was haemorrhaging cash, WeWork was valued at more than $40 billion. Two years earlier, then-chief executive Adam Neumann declared: “Valuation and size today are much more based on our energy and spirituality than on a multiple of revenue.”

Indeed, energy and spirituality abounded. WeWork, which rents and converts office space, described itself as “a platform for creators that transforms buildings into dynamic environments”.

With its plush interiors, 24/7 access, co-working desks and ping-pong tables, the company provides freelancers and entrepreneurs with flexible, short-term contracts. It is a physical manifestation of how many see the new digital economy: open, playful, communal.

The company’s largest benefactor, the Japanese behemoth SoftBank, famously plans its investments according to a 300-year vision. But by the end of 2019, less than 300 days after a multi-billion-dollar injection of SoftBank cash, the markets decided WeWork was, after all, just a real estate company.

A planned IPO was shelved. Neumann stepped down. Thousands lost their jobs. The company suddenly seemed to be worth far less than the billions investors had piled into it.

Promoting flexible office culture

Despite the tenuous wisdom of making large venture capital investments in companies that do not own any unique technology, WeWork is still with us. It now has 662,000 members in 37 countries, bringing the ethos of West Coast techies to most corners of the globe.

It recently opened a lavish new 16-storey block in London’s Waterloo. Persian-style carpets, books on how to boost creativity on the Tube and lunchtime wellness and “breathwork” sessions attract members to rent desks from £600 a month.

Mathieu Proust, WeWork general manager UK, Ireland and emerging markets, says: “The way we work is changing and we are at the forefront of this change. People are increasingly expecting something different from their workplace, prioritising culture and technology.”

WeWork might have helped kickstart the flexible office revolution, but the company now has a plethora of competition. There are hundreds of such brands in London alone and many of them are attempting to undercut WeWork on price.

When a number of companies are offering essentially the same thing, it is often “culture” – that nebulous but occasionally priceless framework – which will separate the wheat from the chaff.

Pricing out neglected innovators

So, what does WeWork and similar outfits offer that is truly unique? Critics argue that while such companies once prided themselves on providing the environment for ambitious small-business owners to thrive, they now risk alienating and pricing out that demographic.

Some, looking for community and mentorship, question the value of stylish desks and potted plants in achieving business success. Are we witnessing a change in what ambitious UK startups are looking for when they rent office space?

Oleg Mukhanov, chief operating officer of Steadypay, an early-stage startup that helps provide financial stability to gig economy workers, says the company used WeWork because “as a startup you were pretty much expected to be based in one”. He says of WeWork in 2018: “WeWorks were filled with the spirit of startup and hustle.”

However, as a fast-growing business on a budget, Mukhanov decided: “There are better ways of spending our capital than having a fancy office space. If we need the cool factor, we can always go to a pub next door.”

Catering for a maturing sector

As setting up a small business has become easier, the idea of working in a startup has also become more widespread. 2019 saw a 44 per cent increase in investment in UK startups.

Tushar Agarwal, co-founder and chief executive of HubbleHQ, an office-finding website, which he describes as the “booking.com to WeWork’s Marriott”, says the growth of the startup sector has had a knock-on effect on workspaces.

“The office market has changed more in the past five years than it has in the last fifty,” he says. “We are generally seeing that as the entrepreneurial ecosystem matures and startups become scale-ups, the spaces these businesses want to occupy are also growing up.”

This means that many of the amenities WeWork offer may no longer be as attractive to some as they used to be.

For instance, in the eyes of many founders, having a private office still seems to be an essential ingredient for success. And while bean bags and fridges full of beer are pleasant and good for networking, they are not always great for getting work done.

Companies like WeWork helped to establish the concept of the flexible workplace, but whether the model can be profitable in the long term remains to be seen.

It is difficult to assess whether WeWork and similar offerings can continue to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation. They will no doubt always be an attractive option for some cash-rich businesses that want to prioritise staff conditions, but may not necessarily be the best place for an ambitious, boot-strapped founder to get started.