There is good reason why countries are so keen to host a grand prix. With 425 million television viewers every year, Formula 1 gives host nations high-octane exposure and it puts them on the global sporting map alongside exotic venues such as Monaco and Singapore. Unlike the Olympics and football World Cup, F1 is associated with glitz and glamour, and takes place every year. However, it doesn’t come cheap.

On the face of it, Formula 1 races seem like they should be inexpensive to stage. After all, the only facilities required are seats for spectators and a stretch of tarmac for the cars to race on. In reality this couldn’t be further from the truth.

Setting up street races

There is no such thing as hosting a grand prix on the cheap, but the quickest way to pull it off is to run a street race. They tend to be located on public roads in cities or on the outskirts of town, while permanent circuits are purpose-built venues designed specifically to host high-level motor races.

Street races are cheaper to stage than those on purpose-built tracks since they don’t require construction of a new venue. They also promote the host nation more effectively as local city landmarks are seen by the millions of TV viewers.

However, the annual running costs of a street race are far greater than those of one on a permanent circuit. This is because temporary grandstands need to be built and the roads need to be upgraded to F1’s high safety standard, which is known as grade 1 homologation and is set by its governing body, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile.

There is no such thing as hosting a grand prix on the cheap, but the quickest way to pull it off is to run a street race

At a total cost of $16 million, staffing is the biggest single expense for operators of street races with the marketing and organisation team alone requiring a budget of around $6.5 million. In total, running a street race requires a crew of around 600 with the vast majority being temporary workers. That excludes 120 firefighters and 550 marshals who are often volunteers.

Next comes rental of grandstands which costs around $14 million for structures with 80,000 seats. Securing a 3.2-mile street course with safety barriers and fencing costs in the region of $8 million which is also how much it costs to rent the pit buildings. Vehicle, office and utilities payments are around $6 million, with a further $4.5 million of miscellaneous costs, including cranes and approximately 350 fire extinguishers which need to be placed every 15 metres around the track. Capping it all off is a payment of around $1 million for insurance.

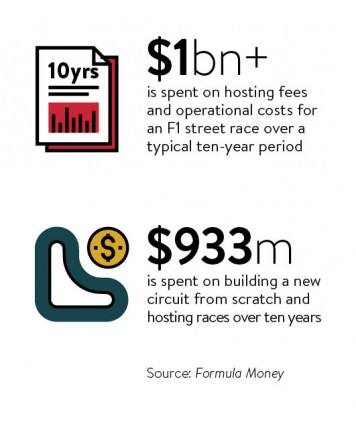

In total, the annual operating cost of an F1 street race is in the region of $57.5 million. Then comes the hosting fee. The average F1 race hosting fee is around $30 million, but the sting in the tail of the contract is that the price increases by as much as 10 per cent every year. Most new F1 race contracts are for ten years so by the end of the agreement the annual fee comes to $70.7 million thanks to the escalator clause in the contract.

It means that over the ten-year race duration, the bill for hosting fees totals an estimated $478.1 million with the costs of running the race amounting to $575 million. It brings total expenses to a cool $1 billion.

Assessing alternatives

One way to avoid the high annual running costs is to host a race on a permanent facility. While this doesn’t require repurposing roads and building temporary facilities every year, it does incur a huge upfront cost.

There are two possibilities. The first is using an existing circuit, but this means the promoter has to settle for whatever flaws it comes with and, unless it has been designed with F1 in mind, it could also require significant conversion costs to ensure it is up to grade 1 homologation. This alone can run into tens of millions of dollars, but the rewards can be rich.

Last November, the Mexican Grand Prix returned to the F1 calendar after a 23-year absence with a race on the Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez track in the heart of the country’s capital Mexico City. It was home to the previous race and has been given a new lease of life, with the highlight being a new section of track weaving through a baseball diamond which was packed with fans on race day.

A total of 90,000 fans flocked to the track on Friday, 111,000 on Saturday and 134,850 for the race on Sunday, generating an overall attendance of 335,850. Eye-catching “Back in Mexico” banners were draped all around the circuit, but the real impact was felt further afield.

According to industry analysts STR Global, the night before the race the average daily rate in Mexico City hotels was $258.79, a 128.1 per cent increase on the same day the previous year. Occupancy in Mexico City hotels was also up and rose 64.4 per cent on the same day in 2014 to 81.8 per cent. Hotels, therefore, benefit from the race being in the heart of the city, which usually isn’t possible when building a track from scratch as so much space is required.

The most successful example of this is F1’s newest purpose-built track, Circuit of the Americas in Austin, the capital of Texas. It has hosted the United States Grand Prix since 2012.

Designing a track from scratch gives the promoter complete creative flexibility, which can make all the difference when it comes to attracting interest in the race. In its first two years, the US Grand Prix had the second-highest attendance of any race, but slipped to fourth in 2015 as it was awash with torrential rain.

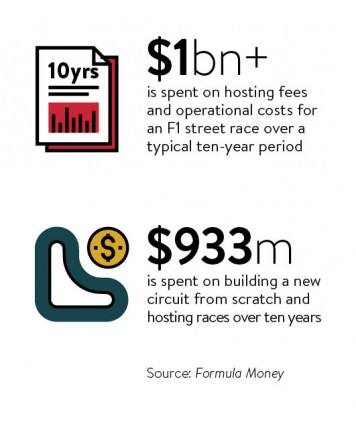

Building the track cost around $270 million and then comes the hosting fee as well as the annual running costs which, at around $18.5 million, are far lower than those for a street race.

It means that over a typical ten-year period, building a grand prix circuit and hosting an F1 race costs around $933.1 million. Ironically, paying this is the easy part of the process. The race organisers then have to sell all the tickets, promote the event and ultimately showcase the host country to the world. That is F1’s grand prize.

REVERSING SILVERSTONE’S FORTUNES

The British Grand Prix should logically be the most secure race on the Formula 1 calendar as its home of Silverstone hosted the first race of the championship in 1950 and has the highest attendance. However, talks are now underway about selling a lease on the track to luxury car manufacturer Jaguar Land Rover to secure the future of the race. So how did this happen?

Built on the site of a former airfield, Silverstone is owned by the British Racing Drivers Club (BRDC), a group of 850 racing luminaries including Nigel Mansell, Damon Hill, Jenson Button and current F1 champion Lewis Hamilton.

Over the past six years, the BRDC has tried to sell a long lease on Silverstone to reduce the club’s exposure to risk. The British Grand Prix is the only event on the F1 international calendar to receive no government funding. Instead, Silverstone has to use the proceeds from ticket sales and has had to boost prices to match annual increases in the F1 hosting fee, which comes to an estimated £17.6 million this year.

The track has also been suffering from a loss of rental income after leasing 280 acres of surrounding land in 2013 to business park operator MEPC to clear is debts. The BRDC’s plight has led to it paying the hosting fee for the British Grand Prix in arrears meaning that a letter of credit from bankers is necessary for the race to go ahead. As every year goes by the pressure on Silverstone increases because the price of its F1 race hosting fee rises by 5 per cent annually.

Setting up street races

Assessing alternatives