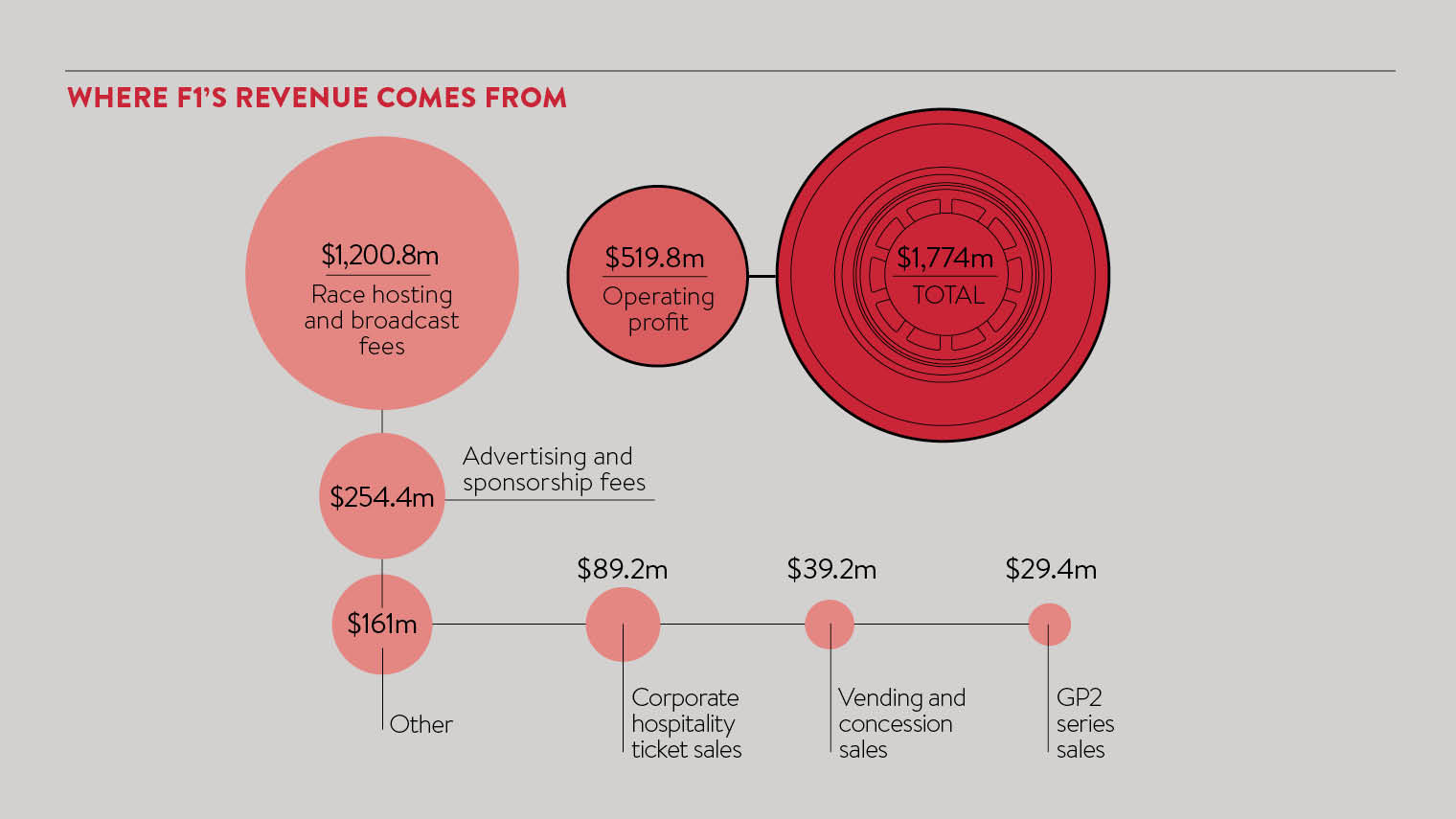

The core revenues of Formula 1’s parent company come from selling the rights to host and broadcast races as well as advertising and corporate hospitality at the tracks. In the early days of F1, teams made separate deals with grand prix promoters and television coverage was sporadic as it could be cancelled at the last moment if there were not enough cars to fill the grid.

F1 chief executive Bernie Ecclestone, who was then owner of the championship-winning Brabham team, saw that cash would come from television. In 1981 he convinced the teams to sign a contract committing them to race. He then took it to TV companies so they could guarantee coverage. His company Formula One Promotions and Administration negotiated the deals and took a share of the proceeds with the remainder going to the teams and the governing body the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile.

Click here for the full infographic

Showcasing the big names

With guaranteed TV exposure, sponsors’ rates increased giving the teams more money to spend on cutting-edge technology in a bid to win. In turn, this attracted the best drivers which made the series even more appealing to broadcasters. Big name car manufacturers, such as Honda, Renault, Porsche and Lamborghini, became involved through supplying engines to the teams.

Fierce rivalries and intense battles for championship supremacy were the norm in the 1980s with Alain Prost, Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet all vying for glory throughout the decade. However, it was Brazil’s Ayrton Senna driving for McLaren who got everybody talking. Arguably one of the most iconic images of the era was his controversial clash with team mate Prost in Japan in 1989. It put both drivers off the track and although Senna made it back on to win the race, he was later disqualified for using an escape road to rejoin the circuit, handing the title to Prost.

The Brazilian also dominated the early-1990s, winning consecutive world championships in 1990, following yet another controversy in Japan with Prost, and in 1991 after a dominant season with McLaren.

With guaranteed TV exposure, sponsors’ rates increased giving the teams more money to spend on cutting-edge technology in a bid to win

British hopes too were rewarded at last in 1992 when, after years of frustration and retirement threats, Nigel Mansell stormed to championship glory, becoming the first Brit to do so since James Hunt in 1976 and setting the scene for the rest of the decade, which was to be largely dominated by his team Williams. A new era beckoned in 1993 as Prost, now also racing for the British marque, claimed his fourth and final title before taking the decision to leave the sport before the start of the 1994 season.

Things were changing in F1, and with fresh new talent in the form of Michael Schumacher and Mika Hakkinen on the horizon, to many it seemed as good as it could get. Then Senna was killed at the San Marino Grand Prix in 1994 after crashing out from the lead and it looked like the sport was facing its darkest hour. However, Senna’s death drew the world’s attention to F1 at a time when there was plenty of drama on the track and the sponsors were pumping in significant financial support.

The Schumacher years

Over the next few years, television audiences soared, particularly in Germany where fans were rewarded with their first champion when Schumacher took the 1994 crown for his Benetton team.

Another dominant title for Schumacher followed in 1995 in his final year at Benetton before heading to Ferrari. It heralded the beginning of a career that, though often shrouded in controversy, would earn him a place among the legends of F1 thanks to a record-breaking total of seven titles.

His first win at Ferrari came at the 1996 Spanish Grand Prix in poor conditions, showcasing his skill and allowing audiences worldwide a glimpse at his superstar status. Schumacher went on to finish his first season for Ferrari in third position, behind the seemingly unassailable Williams. He was able to take the fight to Williams’ Jacques Villeneuve in 1997, just a single point behind when the championship rolled into Spain for the finale. But a shunt with the Canadian put Schumacher out of the race and ultimately he was stripped of all championship points for causing the collision.

He was runner-up in 1998 behind Hakkinen and a broken leg in a crash at Silverstone the following year kept him out of the title fight. By 2000, Schumacher and Ferrari were back on form and their dominance of the 21st century began, cementing Schumacher’s position in the history books with five titles from 2000 to 2004.

As the on-track action electrified it made F1 even more attractive to TV stations and in 2001 Schumacher’s success brought it to the attention of German media giant Kirch. It borrowed $1.6 billion from three banks to acquire a 75 per cent stake in F1. State-owned German bank BayernLB loaned $987.5 million with Lehman Brothers and J.P. Morgan each providing $300 million.

However, Kirch lacked the key to a fortune as the terms of a 1999 bond issue prevented F1 from paying a dividend. By the time Kirch collapsed under the weight of its debts in 2002, it had not made any money from the sport and, to this day, remains the only shareholder not to have received a return.

CVC and the future

The loans from the trio of banks were secured on the F1 stake and when Kirch went into administration they enforced their security. However, in the vacuum, they lost control of the business. When CVC, the private equity firm, bought the business from the banks, it didn’t make the same mistake twice.

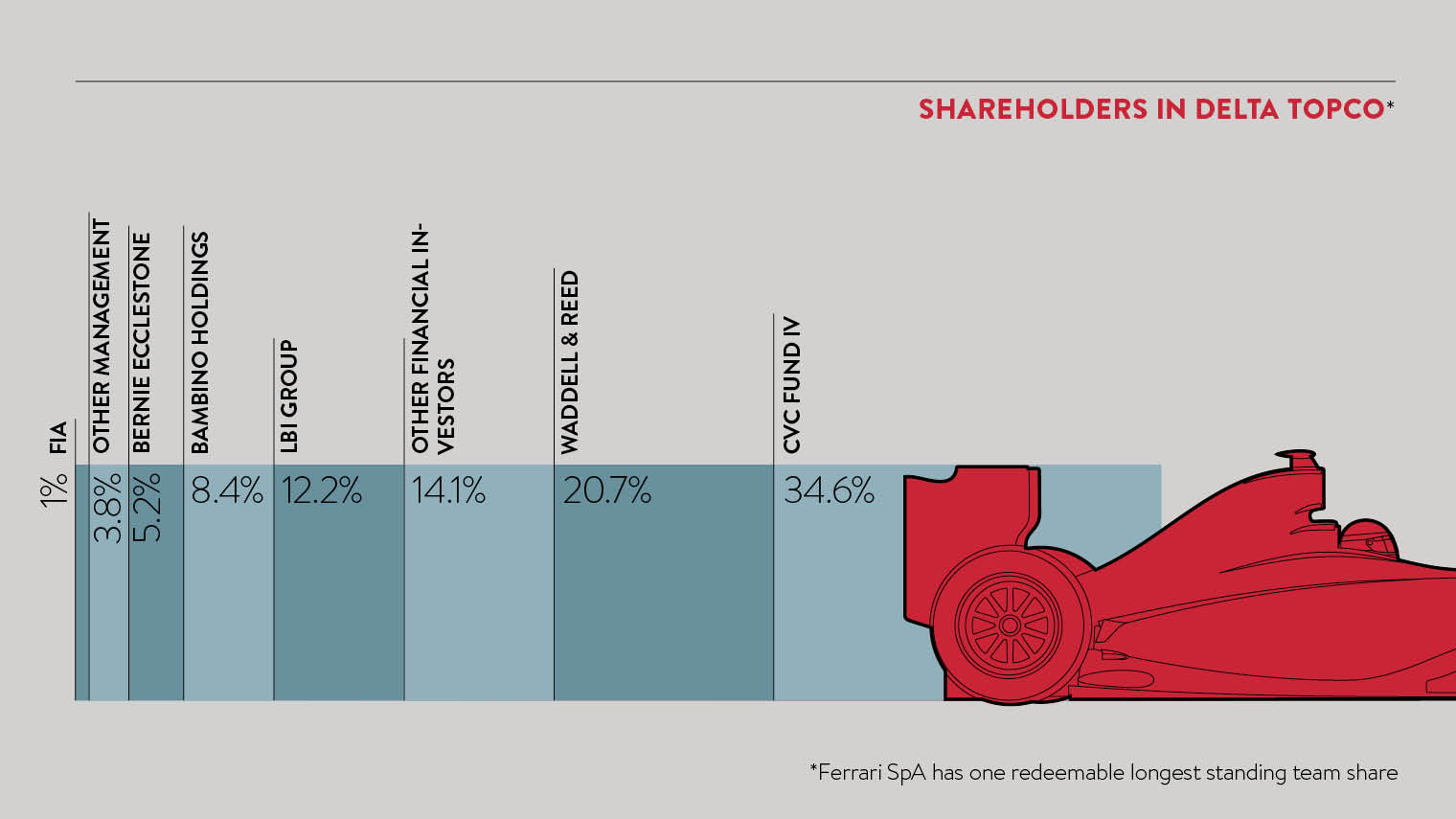

It has given CVC a 351.8 per cent return on investment and its remaining shares are worth another $3 billion

CVC bought F1 in 2006 in a leveraged buyout funded with two loans – $965.6 million from its investment Fund IV and $1.1 billion from the Royal Bank of Scotland. It covered its back.

Buried in the articles of association of F1’s parent company Delta Topco is the revelation that CVC’s shares entitle it to appoint representatives, known as I directors, who can “exercise one vote more than the total number of votes exercised by the other directors”. The articles add that the purpose of this is “to ensure that the I directors will always have sufficient votes to pass a resolution of the board”.

This control puts a huge premium on CVC’s stake and its riches were unlocked with a debt refinancing which allowed dividends to be paid.

Over the past decade CVC has halved its stake to just under 35 per cent and reaped a $4.4-billion reward which comprises 31 per cent of the total generated for F1’s owners. It has given CVC a 351.8 per cent return on investment and its remaining shares are worth another $3 billion at the latest valuation of the business from $8.6 billion to $10 billion.

To put this in context, CVC had made 314 per cent on its €184 million investment in British bookmaker William Hill by the time it exited through share sales and an IPO in 2002. Likewise, the £30 million CVC invested in stockbroker Collins Stewart generated a return of 292 per cent from share sales and a 2002 IPO. Its biggest return is believed to have been from the 2005 sale of Spanish hospital operator IDC which came to 831 per cent. F1 may overtake it if CVC actually sells up.

According to CVC’s co-chairman Donald Mackenzie, there is no need to do this. “There is no end date. We have 12-year funds, which we have to return the original money. We have already done that. So the pressure’s off. We like owning it [F1]; we don’t want to sell it. There are always some people who’d like to buy it – it’s a very good business.”

KEEPING F1’S WHEELS TURNING

It may seem like the biggest decisions in Formula 1 are made on the track, but in fact the most powerful people in the sport are found behind the scenes.

F1’s nerve centre is the paddock, an oblong tarmac space between the teams’ mobile offices and their transporters which back up to the pit garage rear doors. The area was historically a working environment for team staff, but F1 chief executive Bernie Ecclestone has made it one of the most sought-after places to be in world sport.

The motorhomes are where team bosses discuss race strategy, and drivers eat, drink and wind down. They are essentially the drivers’ locker rooms and passes to the paddock cannot be bought. In itself this adds to the allure and exclusivity of the paddock, but that’s just the start. As interest in F1 accelerated so too did the desire for celebrities and VIPs to be seen at the races, and the paddock is the place to find them.

It shouldn’t be confused with the Paddock Club which is where corporate guests network and fuel F1’s multi-million-dollar budgets. Teams give passes to their sponsors who, in turn, invite clients to do business and close deals in the Paddock Club. Potential sponsors are also invited by the teams so that they can get an inside look at what is on offer from a partnership. It keeps F1’s wheels turning.

The Paddock Club is managed by Austrian catering firm Do&Co, which has an army of staff to make the venue work. Hundreds of staff are involved at each race including chefs, catering staff, electricians, security, entertainers, florists, therapists and cleaners.

Security, logistics, construction and catering tend to be handled by the same contractors throughout the season meaning that teams and sponsors know what they will get at any race no matter where in the world it is held.