Formula 1 teams are considered to be the glitziest trophy assets of them all. With logos on the cars of some of the world’s most well-known brands and hundreds of millions of dollars of prize money flowing into their coffers, teams appear to be turbocharged cash cows for their owners. In fact, it’s not so simple.

F1 teams are usually either run to break-even or at a loss which involves the owners pumping in more than the teams make in revenue. And they do it in pursuit of victory. The additional funds tend to come from the owners’ pockets or debt and it is invested on the understanding that it is better to win on the track and make no profit rather than make money and finish low down the standings.

Victory on the track increases a team’s ability to bring in more money from sponsorship since brands are prepared to pay more to be associated with a winner. While team owners can get a financial return from selling a team in the long run, what do they get when it is running to break-even?

Breaking down revenue sources

The answer is that if the owner is a private individual, such as Sir Frank Williams who has a 50.8 per cent stake in his eponymous team, they can take an annual salary.

If the owner of a team is a company which sells products, such as Mercedes, Ferrari, Renault or Red Bull, the benefit they get while the team runs to break-even comes from television exposure of their logos on the cars. It keeps the owner happy, but it is tougher to keep the team ticking over.

Victory on the track increases a team’s ability to bring in more money from sponsorship since brands are prepared to pay more to be associated with a winner

The teams’ revenue generally comes from three sources with each providing a similar amount. They are all fuelled by F1’s global television audience which totals 425 million viewers annually, according to the latest figures. The first key revenue source is sponsorship and in this field money usually talks. The higher the cost, the greater the exposure on the car.

However, some sponsors do not even get presence on the cars and are instead known as suppliers. This is a cheaper alternative and often does not involve a cash cost. Instead, the brand supplies equipment or services and, although they don’t get exposure on TV, they usually receive many of the perks which come with on-car sponsorships, such as passes into F1’s exclusive paddock, use of the team logo in advertising and sometimes even driver appearances at company functions.

Sponsorship comprises around 37.2 per cent of the teams’ revenue with 34.9 per cent coming from their profit-share with F1. The series pays them a total of 63 per cent of its annual profits as prize money which amounted to $863.1 million in 2014. Winning the title that year gave Mercedes an estimated $109.2 million.

Payments from owners provides around 19 per cent of revenue and the marketing benefit from the exposure of the team on TV compensates for this investment despite it being intangible income. The remaining 8.9 per cent of team revenue comes from miscellaneous sources, such as drivers who pay to race. They are a hallmark of teams at the bottom of the grid and there is a huge gulf between their budgets and those of the top performers.

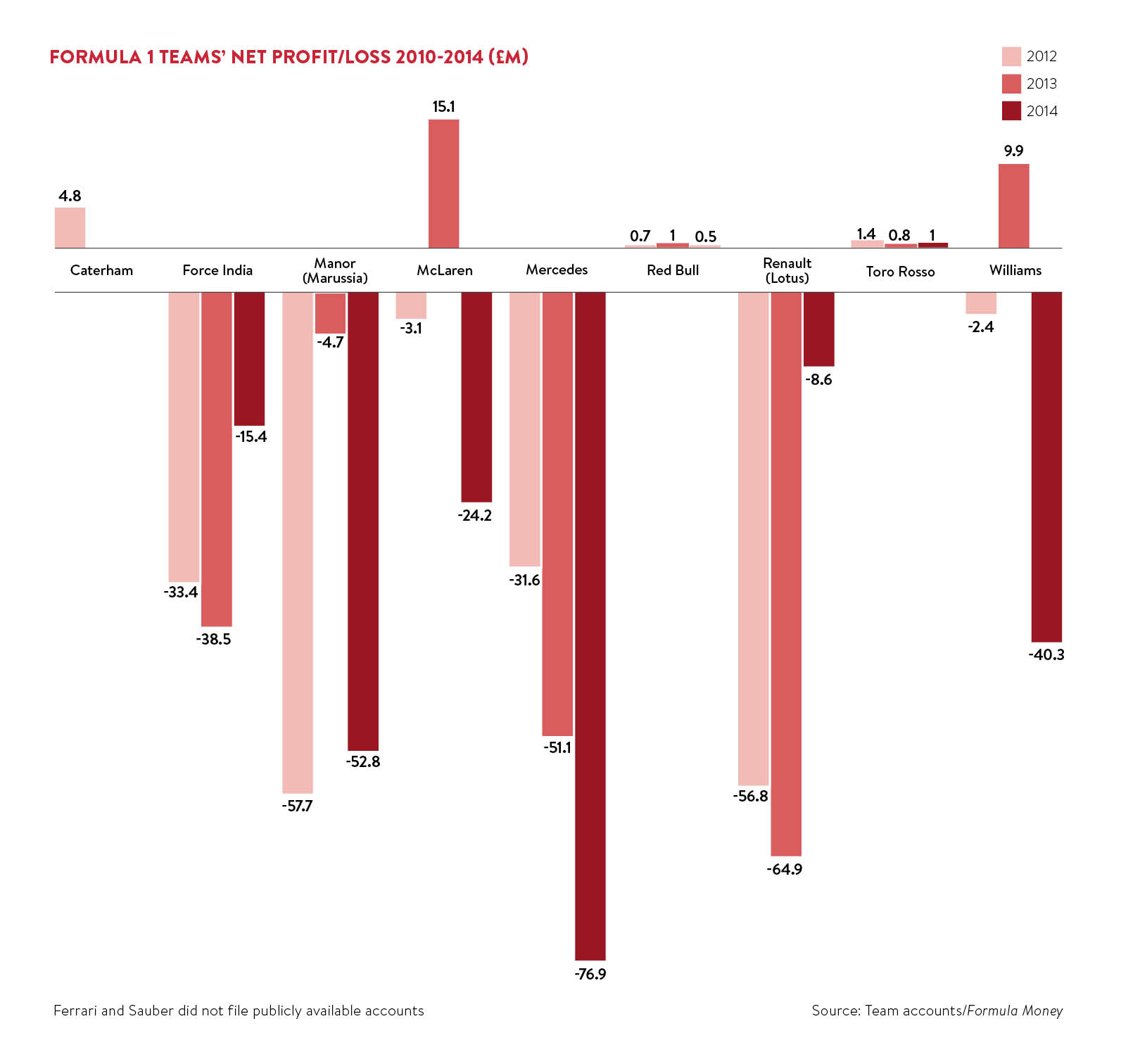

In 2014, a total of nine of the teams filed publicly available accounts with the only exceptions being Ferrari, as its team is a division of the famous motor marque, and Sauber which is based in Switzerland. The nine teams together made £1.4 billion in revenue and the biggest winners were former champions Red Bull Racing which alone accounted for 22 per cent of the total. The team’s biggest benefactor is Austrian drinks company Red Bull which poured in £60.5 million of its £204.6-million revenue.

Although Red Bull had the highest revenue, it only grew 3.6 per cent on the previous year as the team already had the biggest budget. It hasn’t translated into on-track success as Red Bull struggled with F1’s switch in 2014 from a 2.4-litre V8 engine to a more environmentally friendly 1.6-litre turbocharged V6 hybrid. The team won four consecutive F1 championships with Germany’s Sebastian Vettel, but was dethroned in 2014 by Mercedes driver Lewis Hamilton and finished in fourth place last year.

The worst performer was the Marussia F1 team as its revenue reversed by 57 per cent to £26.2 million in 2014 when its owner, Russian tycoon Andrei Cheglakov, stopped paying the bills. The team has only scored two points since joining F1 in 2010 and finished ninth in the standings in 2014.

In October 2014, Marussia crashed into administration with total debts of £63.6 million and was rescued at the start of last year by Stephen Fitzpatrick, the boss of energy firm OVO. It was renamed Manor and Mr Fitzpatrick reportedly planned to invest £30 million of his own money in the team. It was badly needed. In the year ending December 31, 2014, Marussia’s net losses increased more than ten-fold to £52.8 million driven by reduced sponsorship and an increase in costs from the switch to V6 engines.

CASE STUDY: BANKROLLED BY A TYCOON

Esteban Gutierrez and team founder and chairman Gene Hass

This year the Haas Formula 1 team becomes the first American outfit in F1 since the 1980s and has already made an impact.

Before the season began, Haas completed a total of 474 laps in testing which is roughly the equivalent to the distance covered in eight races – not bad for a new team.

Time has been the key to Haas’s success so far. In mid-2014 Gene Haas, the American tycoon who is bankrolling the team, decided to delay his F1 entry from 2015 to 2016. In turn his team didn’t have to sign up to racing regulations until late last year, which meant that it could test for longer without restrictions.

It also gave Haas time to snap up equipment at bargain prices from the Manor F1 team, which crashed into bankruptcy late in 2014.

His shopping list included Manor’s factory in Banbury and around 250 staff work for the Haas F1 race operations there. The design division is based in North Carolina at the premises of the championship-winning NASCAR stock car team which Haas co-owns.

He is also taking advantage of a new regulation which allows teams to buy more parts than before from established F1 marques. Buying in more parts reduces start-up costs and Haas is using a Ferrari engine with a chassis made by Italian manufacturer Dallara.

Initial costs of its UK division were £10 million, in its first five months, which is low by F1 standards. However, according to F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone, Haas will need to spend much more than that. “A billion would last a new team owner four years,” he says. Time will tell whether Haas has got what it takes.