It is difficult to conjure up a more frightening intellectual property nightmare for the straight-laced executives at the Disney Company’s headquarters in Los Angeles than a recent phenomenon 6,000 miles away in Weston-super-Mare. The purveyors of family-friendly themed entertainment par excellence will have been unlikely to have heard of the Somerset seaside town before last August, but they’ll have the name emblazoned on their “risk list” now.

Dismaland, the brainchild of global street art guru Banksy, had a five-week run last summer. And even those who have never been to any of the American grand-daddy of theme parks would have been able to clock the obvious – and intentional – similarities between Banksy’s “bemusement park” and the home that Walt built. A passing glance at the Cinderella’s castle-style logo and the point is made.

Lawyers speculate on just how annoyed Disney’s senior executives were with Banksy. But it’s a safe bet that Dismaland’s Punch and Judy show, featuring a Jimmy Savile look-a-like character, would not have had them rolling around in fits of giggles.

Complexities of IP law

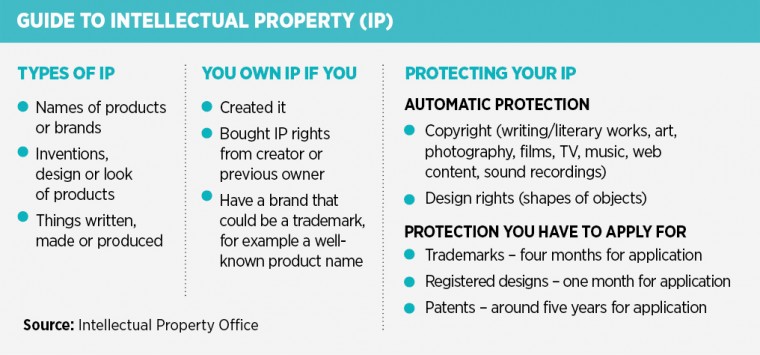

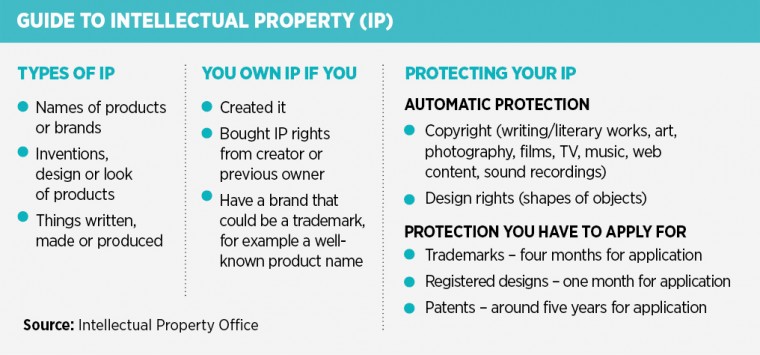

Regardless of how fuming they were, Banksy might have had the last laugh had Disney attacked on intellectual property (IP) grounds. Lawyers point out that the elusive artist could potentially have relied on recent reforms to UK copyright law to send any aggressive legal emissaries packing. About a year ago, UK legislation was amended to allow the defence of parody to allegations of copyright infringement.

Under the revised legislation, if it can be demonstrated that an exhibit – or an entire theme park, for that matter – is a clear parody of an established brand, then the lampooner is likely to be off the hook.

Issues around fair dealing, where an upstart allegedly competes unfairly with the financial interests of a copyright holder, would also be potentially difficult for Disney if its lawyers took on Banksy. “Nobody really knows how that copyright principle applies in cases of parody,” says Matthew Dick, a partner at D Young & Co, a London-based IP law firm of solicitors and patent attorneys, in a candid moment acknowledging legal uncertainty. “It’s a grey area.”

What is known is that Banksy filed a trademark in August for Dismaland that covers the entire European Union. The three-month opposition period is on the brink of expiring, with experts suggesting that Disney’s best course of action will be a challenge based on the grounds of trademark protection.

Trademark issues

“Trademark issues are far more relevant to themed entertainment businesses than patents,” argues Mark Engelman, an IP specialist barrister at Hardwicke Chambers in London. “That’s because theme parks are branded up to the hilt.”

Peter Brownlow, a partner at London IP specialist law firm Bird & Bird, agrees: “It is crucial to all themed entertainment business plans that the right to use the theme is protected. That is after all the main draw for the audience.”

The lawyers point out that almost every element of a themed entertainment enterprise, from thrilling, stomach-churning rides, to cartoon characters, to T-shirts and stationery, has IP embedded in it.

Lawyers maintain the best method of protecting intellectual property in themed entertainment is through iron-clad trademarks

But patents, which protect innovation in the mechanics of an invention, in other words, the way it is built, are far more difficult to obtain than trademarks, which protect branding. To bag patent protection, explains Mr Dick, “there must be some novelty as to how the machine or ride is constructed”.

He cites the Tower of Terror, versions of which are at four Disney theme parks in the United States, France and Japan. The ride takes punters up high before dropping them suddenly. “When that was first developed with a special means of achieving the experience, it couldn’t be achieved any other way,” says Mr Dick. “Then you could try to get a patent that would block others from using the same technique.”

Nonetheless, competitors could try to work round the patent by, say, not using a specific type of air piston.

Protecting your brand

Lawyers maintain the best method of protecting IP in themed entertainment is through iron-clad trademarks. For example, the Der Stuka ride at the Wet ‘n Wild theme park in Florida has created a special reputation among aficionados of the genre. Competitors could copy it, but they couldn’t call it Der Stuka, which is a highly distinctive name, in which, arguably most of the commercial value lies.

Indeed, anyone looking for the manual on how successfully to exploit IP from an existing character in a themed entertainment context should cast an eye over the story of a 12-year-old bespectacled orphan, who just happens to have other-worldly powers.

Love him, loath him or feign ambivalence towards him, you can’t ignore the boy wizard of Hogwarts. Harry Potter is a global brand of almost unparalleled proportions. And no greater manifestation of that brand can be seen than in its themed entertainment portfolio.

The Wizarding World of Harry Potter is a theme park within a theme park, or more accurately, within three theme parks. It launched at Universal’s Islands of Adventure in Orlando in Florida about five years ago. Versions then cropped up at two more Universal Studios parks last year within days of each other, another in Orlando and one in Japan. And a fourth branch of the Wizarding World will finally make its Hollywood debut when Universal rolls it out in the land of the dream factory itself next spring.

But the incredible IP foresight – some would suggest genius – dates back to 1999. Just two years after the first novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone hit bookshops, J.K. Rowling’s lawyers obtained trademarks for entertainment and theme park services. That was more than a decade before the ribbon was cut on a sultry June day in Orlando on the first Wizarding World.

“Harry Potter is a prime example of a clear strategic intention to extend a brand from what started as a simple character in a book to everything beyond,” says Mr Dick. “It was very impressive to have that kind of foresight,” he says with more than a hint of admiration. “To have on their radar so early an idea of how the brand could be monetised through amusement and theme parks – they really got their ducks in a row early.”

It is not just character-branded or rollercoaster-rich amusement parks that are aiming to protect IP in themed environments. Recently Apple, the style trendsetter of the technology world, registered a trademark for the design not of one of its new products, but for the layout of its shops.

In the world of entertainment, whether it is video games or the shops in which the computers they are played on are sold, protecting brain waves is perhaps the most important move innovators can make.

Complexities of IP law