To pass the time during a prolonged dull spell, a stock market analyst recently produced an analysis which showed that at least three quarters of UK businesses in the FTSE 100 index were in some significant way dependent on politics and politicians for a major slice of their profits.

In defence and many other industries, government was a major customer; in transport it created and took away monopolies; in telecoms it controlled spectrum; in pharmaceuticals it approved products; in utilities it regulated prices. And all this was before it granted and took away investment incentives or invented new fundraising wheezes such as the air transport and banking levies or the insurance premium tax.

The observation is worth noting because it underlines that political risk in UK business has always been with us. But it also serves to underline why it is that the current times are so unusual. We have had several decades to grow used to the idea that governments and their regulatory agencies play by the rules so, even if we do not like them much, we know what to expect.

What is now different is that this has gone by the board. Consistency and continuity are so last century. The defining feature of politics today is its sheer unpredictability. The result is that of all the political issues in business, geopolitical risk is probably the fastest growing. It certainly has the ability to play havoc with the best laid plans.

Brexit and political issues in business

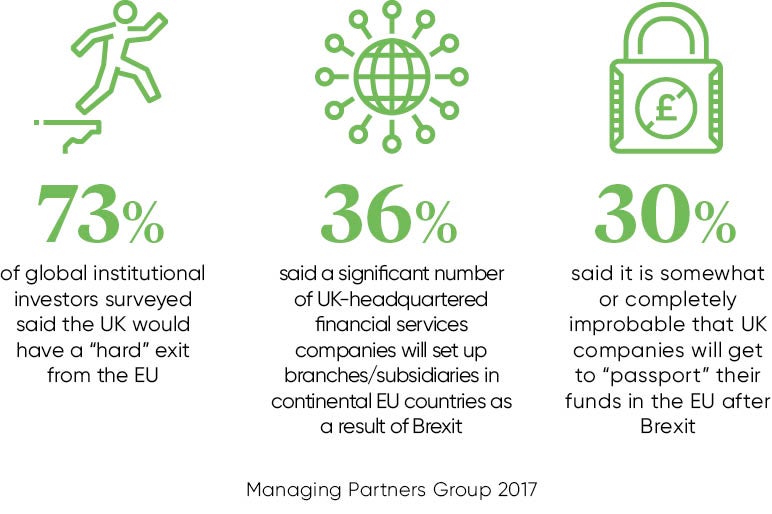

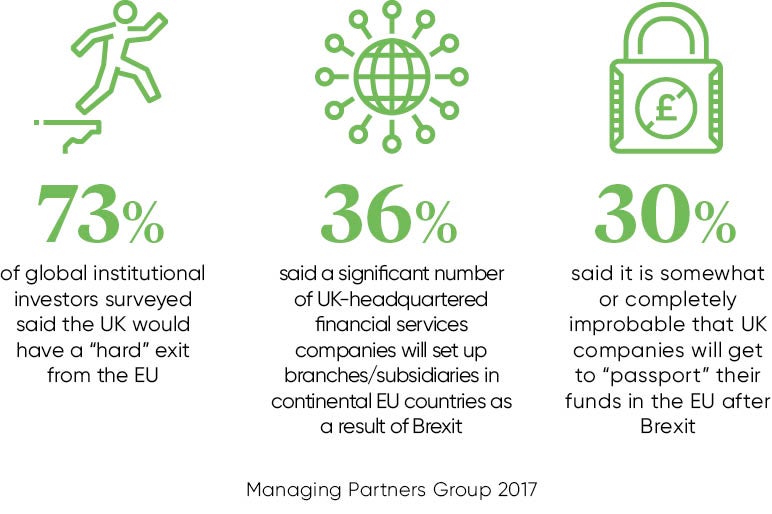

For any UK-based firm or companies with investments here, Brexit must come top of the list of political issues in business. A year ago no major business took as real the possibility that the UK might vote to leave the European Union. But this is what happened and, having spent 40 years trying to harmonise standards, integrate markets and create cross-border supply chains, business now faces the possibility that some, if not all, will have to be undone.

For the financial sector the problems of market access and contract certainty are the main issues, for mainstream UK business it is supply chains, and the fact that components and raw materials might attract tariffs every time they move across a border. Moving to a new order is, in the words of one consultant, like trying to unravel a bowl of congealed spaghetti. The task is complex, costs are high and there is no guarantee at all that the dish will be palatable when the work is completed.

A ticking time bomb of political risk in the UK

But in many ways Brexit is the beginning of the geopolitical story rather than its end. Leaving the world’s richest market to trade even more successfully elsewhere implies that the UK will enter into a rash of trade deals. But each potential partner will demand access to some currently protected part of our market in return for opening up its own. Each deal will come gift-wrapped with its own ticking time bomb of political risk.

Global challenges in business

Meanwhile, however, the world has other issues. More alarming in many ways is the change in administration and tone from the United States following the election as president of Donald Trump. On the campaign trail he accused China of killing America’s manufacturing and Germany of exploiting America with its “grossly undervalued currency”. He promised to make America great again by bringing manufacturing back on-shore, erecting barriers to imports and building a wall to keep out Mexican immigrant labour. No candidate in 80 years had campaigned on such a protectionist platform, let alone been elected on the strength of it.

Whether or not he lives up to the most extreme of his promises is not really the point. The rhetoric is already changing the reality on the ground. Cross-border activity has stalled and investment is flat; international acquisitions are much reduced; globalisation has not reversed, but people talk of its having reached its high water mark. They say history is not linear and even the spreading enlightenment of the Renaissance was halted when Florence’s Medici rulers were toppled. It is a brave company today which bets against Balkanisation. There is much more emphasis on the local.

Each deal will come gift-wrapped with its own ticking time bomb of political risk

Then there is the fate of the EU. Historians have observed that previous periods of prolonged economic stress have led to a resurgence of right-wing extremism and economic nationalism. The Dutch and French elections brought some relief that the tide of populism had been stemmed, but no one, even in those countries, believes the problem has finally been defeated. With more elections to come things could still turn out badly. That in turn could cause a further bout of financial market turmoil and cast a shadow yet again over the sustainability of the euro.

What business leaders need to do

Faced with all this executives have a choice. It might be understandable if they were to retreat into a bunker in the belief that it is just too complicated. That, however, is not the reality of how people behave. True there are moments of paralysis after a particularly egregious shock, but generally they do not last long. Instead business leaders tend to divide risks into two pots. In the first are the really big geopolitical risks about which they can do nothing other than to marshal all the facts at their disposal, prepare contingency plans, and resolve to stay nimble and alert so they can respond fast is something does happen.

In the other pot are all the other challenges with risks from cyber attacks to oil-price shocks, from reputational damage to currency volatility. Here they can do something. Here they can make a difference. And that is what the best businesses do.

Brexit and political issues in business

A ticking time bomb of political risk in the UK