As the tit-for-tat trade war between China and the United States escalates, you might be forgiven for assuming that intellectual property (IP) rights and protections barely exist in China. Yet, despite its reputation as an inveterate bootlegger, trademark squatter and state sponsor of corporate espionage, China is on course to becoming an IP powerhouse.

“Over the past decade, China has demonstrated serious resolve to enforce an effective IP rights regime, and to bring the system in line with other developed systems in the US and Europe,” says Xingye Huang, associate at trademark and patent attorneys Abel & Imray. Indeed, China is on track to achieving its 2020 strategic goal laid out in 2008 of attaining a comparatively high level in terms of the creation, utilisation, protection and administration of IP rights.

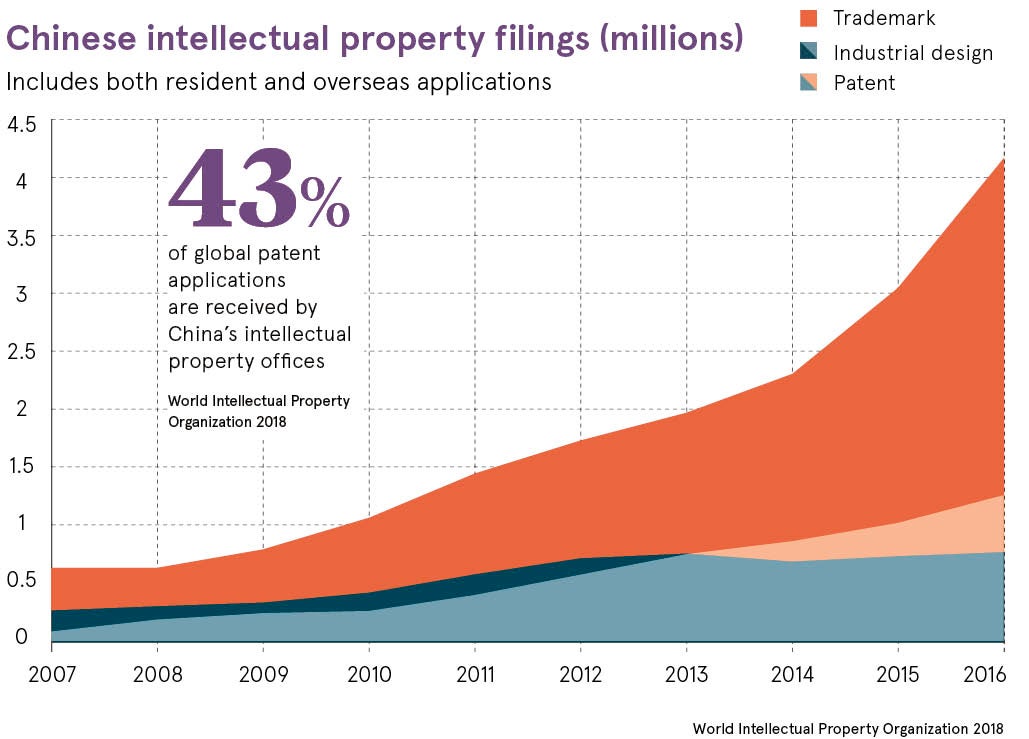

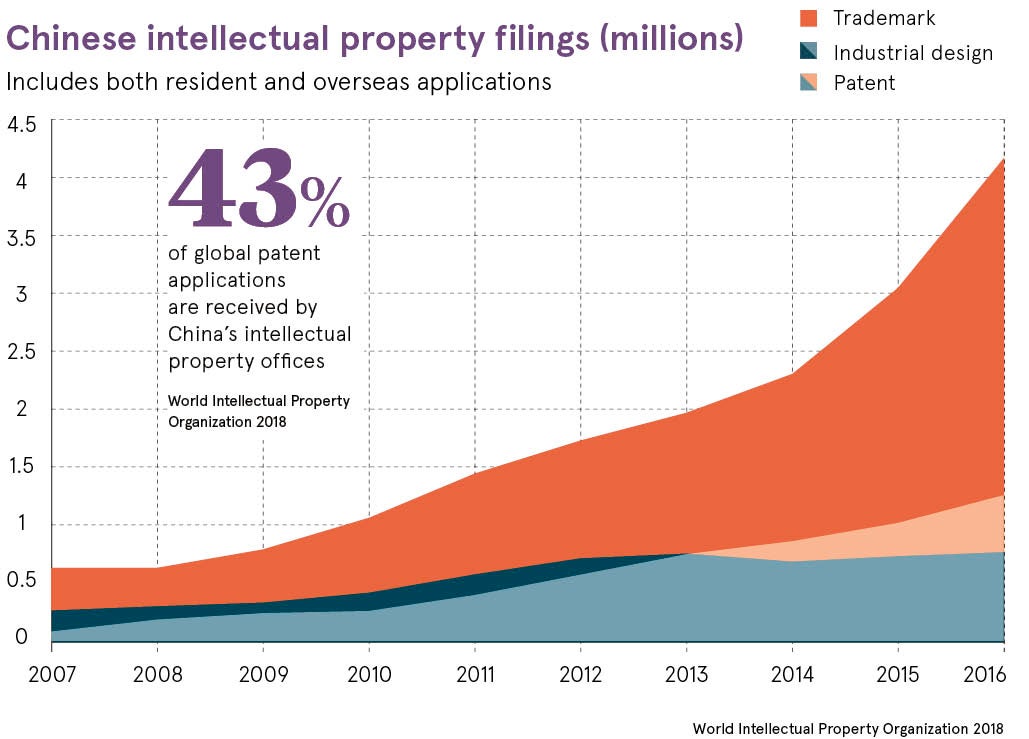

China has evolved from a produce-and-copy economy, which turned a blind eye to copyright infringements in the pursuit of growth at any cost, to one that is focused on high-quality development, as the current official Chinese government slogan puts it. According to the latest figures from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) from 2015, China filed the most patents of any country worldwide. In 2017, Chinese companies registered more than 1.3 million patents, an increase of 14.2 per cent year on year.

China has evolved from a produce-and-copy economy, which turned a blind eye to copyright infringements in the pursuit of growth at any cost, to one that is focused on high-quality development, as the current official Chinese government slogan puts it. According to the latest figures from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) from 2015, China filed the most patents of any country worldwide. In 2017, Chinese companies registered more than 1.3 million patents, an increase of 14.2 per cent year on year.

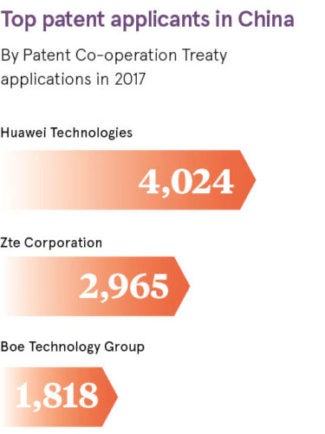

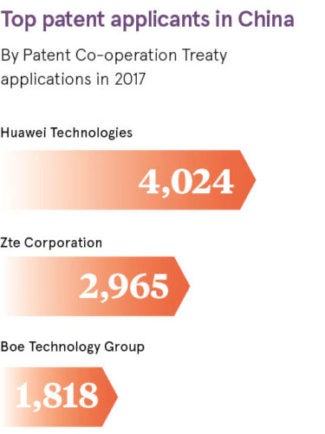

The top filing company at the European Patent Office in 2017 was the Chinese technology giant Huawei. And in high-growth sectors such as blockchain, China dominates as more than half of the 406 blockchain-related patent applications in 2017 were from China, WIPO reports.

Many of the issues raised by foreign companies operating in China have already begun to be addressed by legal reforms and stronger enforcement mechanisms

As Chinese companies focus on global expansion abroad and high-tech innovation at home, they have increasingly called on the government for more robust IP protection. In fact, many of the issues raised by foreign companies operating in China have already begun to be addressed by legal reforms and stronger enforcement mechanisms.

Since 2014, China has opened specialised IP courts and tribunals in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, training attorneys and judges in technical cases. These courts accepted 109,386 civil IP cases in 2015, up 6 per cent on the previous year and which included more than 11,000 patent cases. Whereas in the past, barriers to IP progress stemmed primarily from lack of political will and prioritisation, present hurdles appear in the form of capacity, expertise and scale across the world’s most populous nation, its second-largest economy and a leading global trader.

China’s first intellectual property court opened in Beijing in 2014

“China has a difficult task as it has huge numbers of applications to deal with, a consequence of the government’s drive to increase numbers, but they are having trouble recruiting enough examiners. You need experience to examine well,” says Nick Noble, counsel at patent and trademark firm Kilburn & Strode, and China lead at the Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys.

To this end, China’s State Intellectual Property Office is making great efforts to improve the quality of China’s IP rulings. It sends frequent and large delegations to Germany, on whose legal system China’s is based, the UK and other markets to share and learn best practice.

To act as a deterrent to infringers and to justify plaintiffs’ court fees, the damages awarded by courts are growing. In 2017, amendments to IP legislation increased statutory damages five-fold to RMB5 million or $727,000. In a landmark 2017 ruling that made foreign observers take note, three Chinese shoemakers were ordered to pay New Balance RMB10 million ($1.5 million) for copying the sneaker brand’s logo.

Still, the spectre of corruption haunts China’s law courts. “China has a reputation that local judges are more likely to find in favour of a local company than an oversees one,” explains Mr Nobel, who notes local officials would rather upset a foreign company that is headquartered further away than close-to-home companies in which local vested interests may be entangled.

Corruption rates, however, continue to improve under Premier Xi Jinping’s aggressive anti-graft campaign which began six years ago. Although foreign plaintiffs make up a fraction of the cases seen in China, those suing Chinese companies won some 81 per cent of their patent cases, roughly the same as domestic Chinese plaintiffs. A reputation for fairness is even making China a preferred arbitrator for patent litigation between non-Chinese companies. In 2015, 65 foreign plaintiffs won all their cases against other foreign companies before Beijing’s IP court.

Less than 40 years ago, the concept of IP rights was unheard of in China – now China tutors other nations in its uses

China’s legal reforms and its anti-corruption push form part of a consolidated effort to strengthen the reach and efficacy of the rule of law in China. While rule of law under a one-party state might seem oxymoronic, especially given the party’s historic intolerance of judicial independence as a potential threat to its authority, the current leadership recognises the need to provide predictable, fair and efficient dispute resolution mechanisms if China is to develop further.

According to Professor Rachel Stern of the US University of Berkeley, the Chinese communist party’s approach to the law is quite different from that of Western democracies. For the party, the law is a tool to realise its policies and objectives. In this instance, the strong legal enforcement of IP will provide security and certainty for domestic and foreign investment and competition.

The deepening friction between the US and China over trade, technology and IP is evidence that we’re entering an era in which national security will override trade priorities. While US President Donald Trump’s administration’s most vocal condemnation has been directed at historic abuses and small-fry counterfeiting and piracy, experts observe that a far greater concern for Washington is Beijing’s strategic investments in the decisive technologies of the future. China is consolidating its position as a high-tech superpower in artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, chip making, semiconductors and bioscience.

One of China’s more controversial growth tactics is the practice of requiring foreign companies to partner with domestic firms and in some cases license or transfer their IP. For years the practice was reluctantly accepted by foreign firms as the price of doing business in China, but under the hawkish Trump administration it is again subject to scrutiny. China now bears little resemblance to its 1980s self when the policy was introduced, with a view to investing knowledge and skills in the local Chinese market.

“I think this law will be carefully reviewed and cautiously reformed.” says Abel & Imray’s Ms Huang. “It will get more realistic and reasonable. But for political reasons, it will not be abolished outright.”

At the same time, pending legislation in the US will subject IP deals and technology transactions with foreign entities to even greater scrutiny. In early-April 2018, China announced that it too would follow a similar route. Under new regulations issued by the State Council, technology and IP transfers that are part of acquisitions made by foreign firms in key areas, such as patents, integrated circuit layout design, computer software copyright and plant varieties, will be approved on a case-by-case basis according to their impact on national security.

Foreign businesses operating in less commercially sensitive areas will find that if they make the effort and devote the resources to registering their IP in China properly, protection does exist and enforcement is improving. Less than 40 years ago, the concept of IP rights was unheard of in China – now China tutors other nations in its uses.