Booking a summer holiday for 2016 is fraught with potential problems. If you opt for any time between the August 5 and 21, you’ll be away during the Rio de Janeiro Olympic and Paralympic Games. But if you’re keen to get away before the schools break up, there’s a chance you’ll be watching the 2016 European Championship football final on July 10 from a bar stool in Spain.

Holiday planning logistics aside, this summer promises to be another exciting time for the sporting spectator. But what impact does staging these types of major sporting tournaments have on the host cities themselves? And why do countries place such importance on winning major event bids?

According to Bloomberg Business, Brazil spent $11 billion on hosting the World Cup in 2014. It was money spent in a push to increase the nation’s visibility, consolidate “an image of happiness” and boost the country’s tourism potential, according to a government-sponsored preamble.

So is the high cost of staging the world’s pre-eminent football tournament worth it? The FIFA World Cup does have a precedent for improving overseas visits to emerging destinations. After hosting the 2010 tournament, South Africa’s international tourist arrivals grew at an annual average rate of 7.4 per cent in the three years through to 2013 when it received 9.6 million foreign visitors, the World Bank says.

Brazil hasn’t been so fortunate. The flow of tourists remained flat over the 12 months since the July 2014 final.

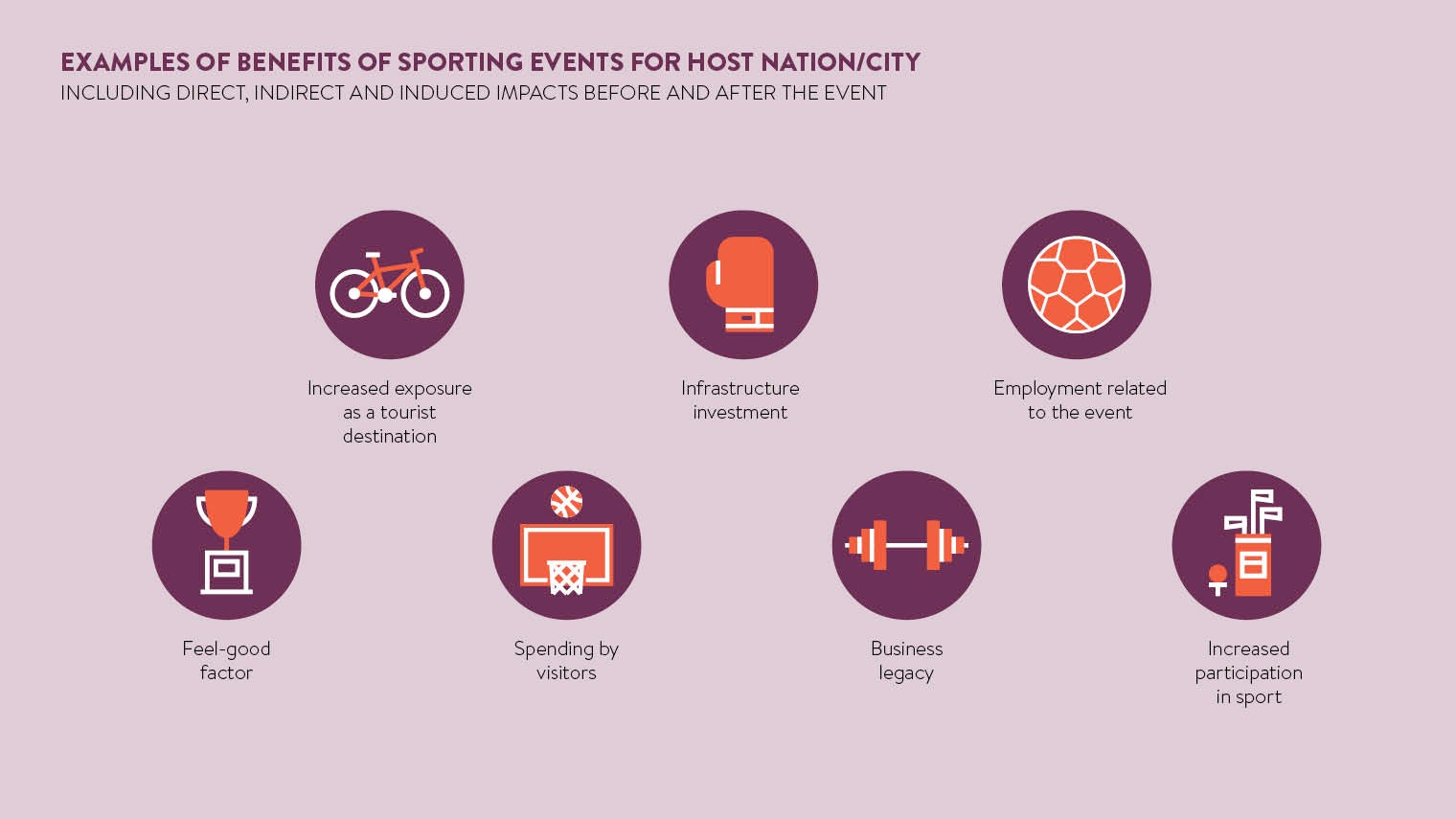

Click here for the full infographic

Measuring return on investment

According to a 2015 joint report by hospitality consultant HVS and advisory service for hotel investment in South America Hotelinvest: “The World Cup’s impact on tourism and hospitality in Brazil was fleeting, and its legacy was a little frustrating. Beyond the renovation of a few airports and modernisation of part of the hospitality infrastructure, probably the most lasting milestone was the 7-1 defeat that Brazil suffered at the hands of Germany.”

However, it hasn’t curtailed hotel groups such as Hyatt, InterContinental and Accor SA from continued opening sprees of new properties across Brazil’s major cities.

Hilton Worldwide opened its debut property in Rio de Janeiro in April last year, citing this year’s Olympic Games and a combined visitor legacy from both the World Cup and Olympics as key reasons for its decision to expand into Brazil’s tourism capital.

The nine-storey Hilton Barra Rio de Janeiro is a stone’s throw from the Olympic Park and just 15 minutes to the best beaches in Barra.

“Hotel groups still believe there’s systemic growth in the Brazilian market, driven by the added halo effect of this year’s Olympics, plus a decline in inflation and tentative growth in the Brazilian economy,” says David Hornby, founder and chief executive of Why Not, a consultancy business for the sports, tourism and events industry. “It’s true that a major event will often act as the catalyst for looking at opening hotels in certain cities, but the longer-term business case still has to stack up.”

Assessing the social impact

For the Chinese capital Beijing, which last year secured the 2022 Winter Olympics despite a dearth of natural snowfall in the region, being named as host city by the International Olympic Committee is as much about the global prestige as it is about the local economic and social impact.

That said, however, a key component of Beijing’s winning bid was its pledge to tackle the city’s air pollution, which was so visible to global television audiences during the 2008 Olympic Games.

Beijing’s victory over Kazakhstan to stage the 2022 Olympic event is also seen as a huge boost to China’s attempts to build a £500-billion sports industry that would create millions of new jobs.

Gaining a significant national and regional economic return, along with increased participation at grass-roots level, was part of the strategy for hosting last year’s Rugby World Cup in England and Wales

Closer to home, France’s successful bid to host this summer’s European Football Championship was centred around developing a modern generation of sports venues for the regions.

Having hosted major international sporting events in the past, such as Euro’84 and the World Cup in 1998, France was able to highlight its experience and expertise. But its stadiums had grown old and tired.

According to official French government figures, building new stadiums and modernising historic grounds, such as Marseille’s Stade Velodrome, has cost €1.6 billion (£1.2 billion). But it will result in the biggest-ever Euro Finals come June 10, with 51 games staged in ten different locations, including new stadiums in Bordeaux, Lille, Lyon and Nice.

It’s hoped that the new stadiums will bring new impetus to French football, both amateur and professional. The average capacity of French stadiums has now expanded from 27,000 to 35,000 spectators, which in itself should generate €183 million in additional revenue for the clubs.

Pulling in the international crowds

Gaining a significant national and regional economic return, along with increased participation at grass-roots level, was also part of the strategy for hosting last year’s Rugby World Cup in England and Wales.

The tournament was staged across 11 cities and 13 different venues, from Brighton on the south coast to Leicester in the Midlands and Newcastle in the north.

“An Olympics is rarely held outside one city, but the wider geographic coverage of something like a European championships or the Rugby World Cup has helped to ensure the economic benefits can be more broadly spread,” says Why Not’s Mr Hornby. “Last year’s tournament provided rugby fans across England and Wales with accessible venues to support their team.”

Rugby World Cup 2015 saw record demand for tickets and an estimated extra 466,000 overseas visitors arriving in Britain during the tournament.

Calculating the likely number of international visitors was based upon the total number of tickets available, plus a survey of interest in purchasing tickets among worldwide rugby fans, carried out by the tournament’s database holder Front Row.

EY predicted visitors would spend up to £869 million in host cities during the tournament. While overall, Rugby World Cup 2015 is thought to have generated up to £2.2 billion from ticket

sales, stadium spending, infrastructure investment and indirect effects such as hotel stays, restaurant bookings and money spent on the high street.

So were these predictions correct? EY’s economic advisory director Peter Arnold says we’ll have to wait a little longer for the firm’s post-event study which is due out in April.

He says: “What we do know now is that organisers sold 2.4 million tickets, compared with an anticipated 2.2 million, so every game was full. The key indicators for us are how many people came from overseas and how much did they spend. With the tournament achieving everything it set out to do and more, our predictions should be pretty similar to the actuals.”

According to tourism body VisitBritain, tourists who come to the UK for these major sporting events are among the most beneficial to the economy because they traditionally stay for longer, have a propensity to travel around the country and spend more money when doing so.

VisitBritain’s director Patricia Yates says: “The Rugby World Cup drew significant volumes of visitors from Australasia, Africa, North America and Europe, staying an average of 24 nights. And with 48 matches spread across 11 host cities, the benefits were felt right across the regions.”

VisitBritain’s research recorded a record-breaking 12 per cent rise (3.4 million) in the number of inbound visitors for October 2015, compared with the same month the year before. It’s fair to assume that a significant proportion of this figure would have come to experience the thrill of a major sporting event that saw New Zealand lift the Webb Ellis Cup for a record third time on October 31 at Twickenham.

Let’s face it, they won’t have come to get a sun tan.

Measuring return on investment

Assessing the social impact