Asset management has always been about more than simply managing assets. There is a strategic dimension to the discipline. It is this intrinsic connection to the bigger corporate picture, though, that means as the wider business world changes, so must asset management evolve too.

The challenge is to think beyond risk and count in metrics other than cash, says Richard Edwards, president of the Institute of Asset Management. “Risk is an important consideration in decision-making, but asset management is about delivering value and is defined as such in ISO 55000,” he says. “This requires real clarity about what constitutes value for each organisation and its stakeholders. Money is likely to be part of this, but value means much more, including reputation, safety, sustainability, community and wellbeing.”

According to Mr Edwards, the overall shift in focus from risk to value has been most prevalent initially in strongly regulated industries, such as energy, water and transport, in the UK and Europe, as well as in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, where it is the public sector that has taken the lead.

Other countries leading on implementation in asset management include the Netherlands, China, and some in the Middle East, says Norberto J. Levin, chief executive of Levin Global, an asset management consulting firm, working mostly in Latin America, but also in the United States and Europe.

Non-physical assets

As the professional remit expands, Mr Levin sees a move away from exclusively physical assets as inevitable. “Currently, asset management is still mostly focused on physical assets, but down the road that focus will expand to include non-physical, which in many cases can be valued significantly higher,” he says.

As a result, interest and investment in enterprise asset management is strong and growing, says Steve Treagust, global industry director of finance, human capital management and strategy at IFS. For businesses managing asset optimisation of ageing infrastructure, alongside demands of corporate social responsibility and sustainability regulation, the approach to intangibles still follows fundamentally familiar lines, he says.

“If you have heavy, tangible assets, typically your perception is based on sweating those assets,” says Mr Treagust. “Moving towards more intangible assets, this perception is likely to carry through. Organisations will look to get value out of those intangible assets, like skills, training and branding. This thinking is becoming more prominent in the boardroom. Drivers include ethical investment portfolios.”

When it comes to environmental and ethical exposure, investment community keywords are responsibility and resilience, transparency and trust. The objective, however, is still one of contextualising and quantifying risk, with implications for asset management, says Jacob Messina, head of sustainability investing research at RobecoSAM. “Sustainability challenges are shaping the competitive landscape, and companies that take the lead in seizing opportunities and managing risks are best positioned to outperform their peers,” he says. “As more asset managers adopt this view, companies will benefit with longer-term shareholders.”

External factors

Asset management does not happen in a vacuum. The environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria used to assess risk and opportunities cover issues from climate change and urbanisation to poverty and diversity.

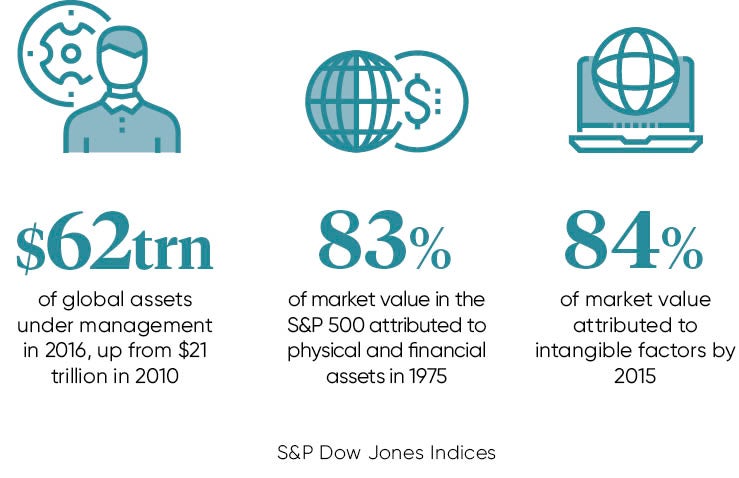

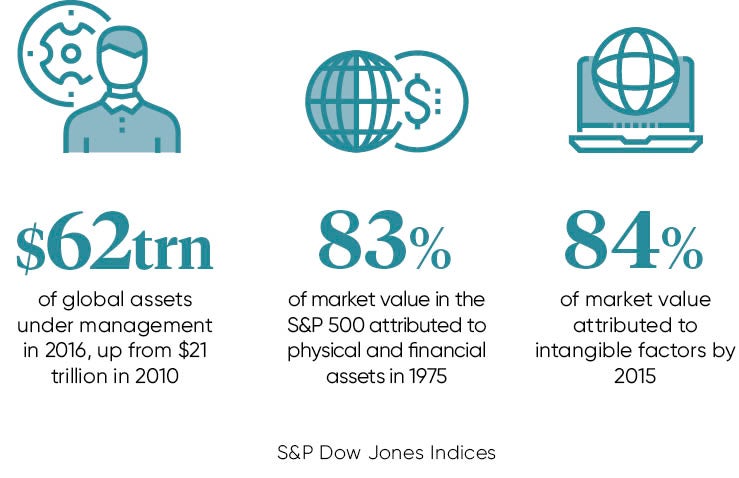

Significant market growth in sustainable investing is impacting the whole value chain, as evidenced by figures for the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), argues Martina Macpherson, head of ESG at S&P Dow Jones Indices. “Global assets under management linked with companies that are signatories to the PRI almost tripled to $62 trillion in 2016 from $21 trillion in 2010,” she says. “Responsible investment now stands at 26 per cent of all professionally managed assets globally, with Japan the fastest-growing region.”

Digital transformation has definitely elevated the importance of asset management

The shift has been dramatic, with near-inversion of the original order, adds Ms Macpherson:

“In 1975, 83 per cent of market value in the S&P 500 was attributed to physical and financial assets; in contrast, as of January 2015, an average of 84 per cent of market value was attributed to intangible factors, which may be bolstered by companies’ commitment to ESG.”

The picture is one of a market not just changed, but transformed, says Mr Treagust. “This is a huge swing, although it took about a quarter of a century. Where this is most evident is in social media companies. Snapchat, for instance, has no tangible assets and its entire value is made up of intangibles. Twitter and Facebook are a similar story,” he says.

Board buy-in

Against this backdrop of integrated reporting, intangibles and sustainable investment, appreciation of asset management amongst the C-suite remains poor, however, Mr Levin concedes. “Boards and C-levels are generally focused on the short term – quarter and year profits, EBITDA [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation] and share value – rather than total cost of ownership and maximising shareholder value for the long term.”

There is still a sales job to be done pitching the case upstream, adds Mr Edwards. “Understanding and adoption of asset management rarely begins at the C-suite; it typically starts somewhere in middle management,” he says. “Those organisations that successfully ‘sell’ concepts upwards to the C-suite are able to articulate in business and financial terms the implications of different funding strategies in the long term, for example a maintenance department able to demonstrate increased capital costs and risks in the future that result from underinvestment.”

One potential game-changer for leveraging benefits of more joined-up thinking and working is maybe not so much investment in human networks as digital ones. Mr Treagust concludes: “Digital transformation has definitely elevated the importance of asset management. If organisations begin to tie physical assets together, implementing the internet of things, blockchain and analysing big data, they will have gained a tangible asset in-between their assets. We will see physical assets speaking to each other, to create a network between them.”

This effectively describes the connective tissue of an “internet of assets”. For the modern asset manager, armed with algorithm-based analytics and data-driven intelligence, it perhaps promises some much-needed muscle in fighting to be heard by the C-suite.