The Uber-driving, Amazon-delivering gig economy has attracted enough scathing comment to embarrass even a thick-skinned disruptive entrepreneur. Yet a picture of low-skilled, exploited masses controlled by platform capitalism and zero-hours contracts is only part of the picture. The story of independent, highly-paid project managers utilised where their skills are needed most, fuelling an agile and flexible economy is largely under-reported.

The Uber-driving, Amazon-delivering gig economy has attracted enough scathing comment to embarrass even a thick-skinned disruptive entrepreneur. Yet a picture of low-skilled, exploited masses controlled by platform capitalism and zero-hours contracts is only part of the picture. The story of independent, highly-paid project managers utilised where their skills are needed most, fuelling an agile and flexible economy is largely under-reported.

However, this on-demand, mutually beneficial slice of the economy is increasingly the lifeblood of many projects across the globe. It’s now pairing world-class expertise with some of the most demanding and complex jobs on the planet, powered, in many cases, by digital technology.

“We are seeing an increase in freelance work at the top end, where individuals have the competences, confidence and demand in the marketplace to give them as much work as they want and when they want it,” says Alan Macklin, deputy chairman of the Association for Project Managers.

UK businesses have spent years trying to become lean and mean in the wake of the financial crisis a decade ago, desperately trying to avoid piling on full-time workers. This has been a bid to keep costs down during the hard times, with a view to springing back during a recovery, but it’s yet to fully materialise. This has fuelled the gig economy.

Why go freelance?

That’s why it’s a great time to be part of the freelancing project management elite; if you have decades of experience and flexibility around where you can work, even better. For example, in management consultancy the average annual full-time equivalent salary when leaving employment and entering the freelance sphere is £127,000 for men and £84,000 for women, according to a survey by consultancy firm Eden McCallum.

This trend will only continue as more businesses see that having fixed roles is ineffective

Increasingly, project management is also the kind of role that businesses see no need to hire as a permanent position. It is now viewed as costly and inefficient to have such people sitting underutilised on the corporate bench.

“At the top end, project managers come in and are able to start work effectively on day one. This model is also faster than full-time hiring. For a business, the ability to have the best resources available instantly is gold dust. It also means they can plan for the total project duration,” explains Charlotte Bohlman, head of customer success at TalMix.

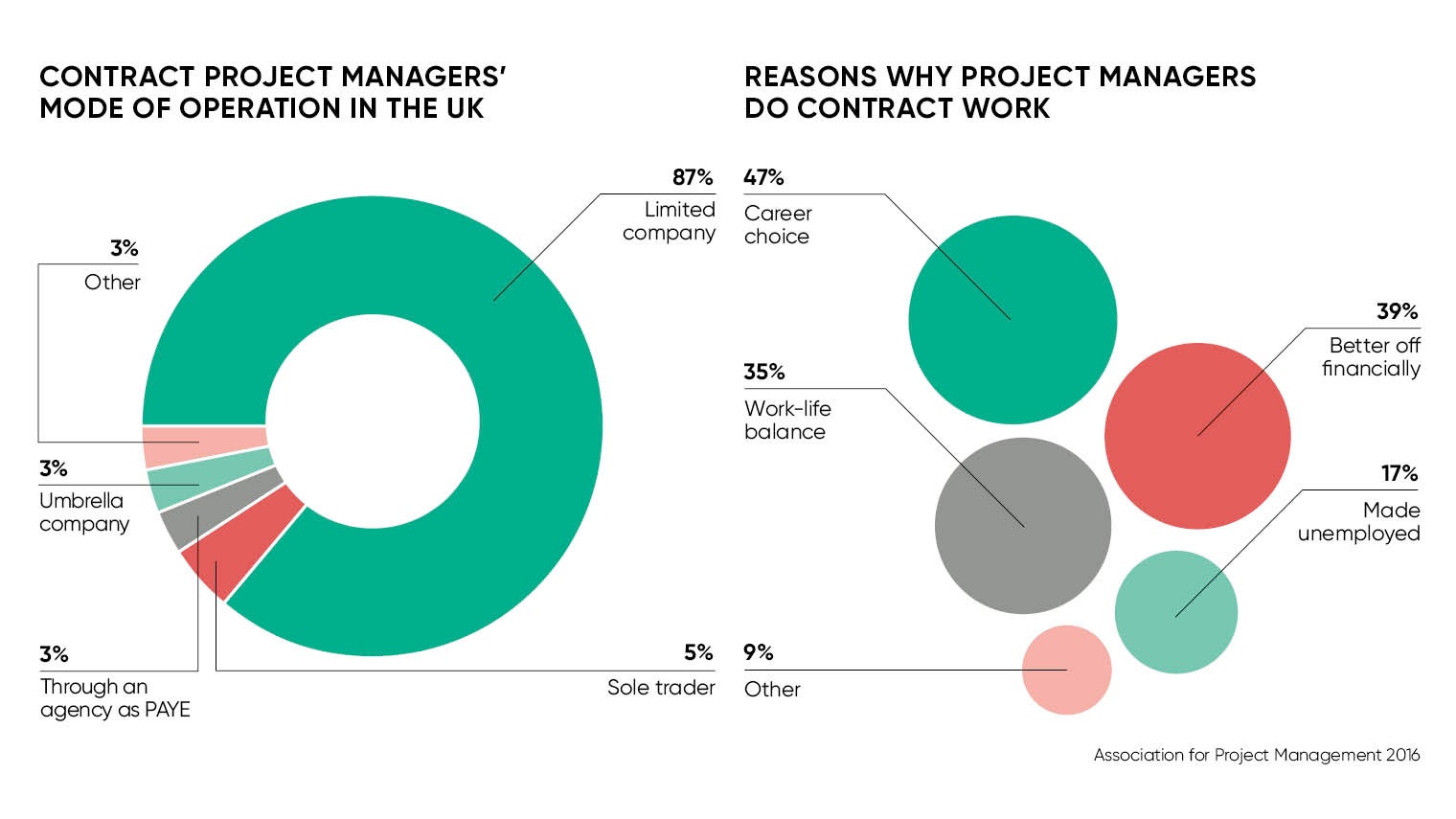

Most independent consultants have left highly paid, senior positions and set up as limited companies, addressing the issues most commonly condemned at the Uber end of the gig economy. The scale of this segment is not to be sniffed at as up to 30 per cent of the working-age population in the United States and 15 European Union founding states now engage in freelance work, according to a report by McKinsey. Also, the UK government has recognised that jobs in the gig economy have played a significant role in current record employment levels.

“This trend will only continue as more businesses see that having fixed roles is ineffective. The gig economy is just the natural partner to the fluid workforce,” says Ms Bohlman. “I believe the gig economy will lose its poor reputation and become a more generic way of describing freelance work.”

The negatives

While gigging could be the cornerstone in a new industrial revolution or growth economy, it is not the panacea to an inefficient labour market as there are downsides: “It displaces the risk on to workers, many of whom are not in a position to deal with it,” explains Professor Birgitte Andersen, chief executive of the Big Innovation Centre.

“Many looking for tenure in a permanent job may instead end up doing endless gigging with no options for pension, sick pay, holiday entitlement, parental leave, or even the likelihood for a skills training course or a stable salary to get a mortgage.”

There is also a reputational risk to companies that bring in talent to manage projects. Permanent staff are more accountable, caring more about a corporation’s long-term standing with clients than freelancers who move from gig to gig.

Permanent managers also have more familiarity and compliance with complex internal systems than those parachuted in, as well as the ability to convince clients about the available skills in-house. The fact is increased freelancing of top-end skills can pose a threat to companies and their ability to sustain the development of more junior staff and marketing their developing skills to clients. There are also other issues.

“There will always be a tension between permanent and gig economy staff, but we are seeing the emergence of more knowledge management systems that support mobile and flexible working,” says Margarete McGrath, digital director at EY.

Certainly, when there is a high demand for projects, there are more project managers who move into the gig economy in a bid to capitalise on this environment. But, when times are tough, companies go to great pains to retain talent, since it gives them a competitive advantage.

Increasingly, there are also disruptive employment models out there taking the gig economy to the next level. For instance, Eden McCallum offers the skills and experience of a major consulting firm, but all its workforce is independent, with the company vouching for the people it takes on.

“When we began the business, saying you were a freelancer was another way of saying you were unemployed; now it’s a recognised and valued career path,” says Dena McCallum, co-founder of the company.

When they first started surveying their consultants ten years ago, only about 30 per cent said they would remain independent for more than three years. Now 60 per cent say they will and only around 5 per cent would consider going back into traditional employment. The gig economy looks like it’s here to stay.

Why go freelance?