Over the last few years, a new phenomenon has hit the UK retail scene, imported from the United States. Black Friday had its first, tentative UK manifestation at the beginning of the decade, when Amazon UK started mimicking its US operation by offering discounts over the weekend after Thanksgiving.

A couple of years later the idea was taken up by Currys and PC World, which advertised an online “price crash” in November 2012 and, by 2014, thanks largely to Walmart-owned Asda, the idea had really taken hold. Excitement about Black Friday was whipped up to fever pitch and riots were even reported at Tesco stores in several parts of the country.

This year, according to a Periscope By McKinsey report, 44 per cent of US shoppers plan to go Black Friday shopping online and in stores, nearly twice as many as last year. In the UK, though, the figure is far higher at 81 per cent.

“Consumer appetite for Black Friday in the US and UK has surged this year, with more planning to shop, in more categories, with more disposable budget,” says Brian Elliott, managing partner of Periscope By McKinsey.

But is this necessarily good news for UK retailers?

In the United States, Black Friday boosts sales at a critical time and has been described as the day retailers begin to turn a profit for the year. However, as Professor Joshua Bamfield, director of the Centre for Retail Research points out, US shopping patterns are very different from those this side of the pond.

“In America, they don’t start Christmas until the day after Thanksgiving, so their Christmas is much more attenuated than in the UK,” he says.

As a result, there’s some evidence that Black Friday simply cannibalises Christmas sales in the UK. It’s certainly something that worries UK businesses. This time last year, a report from LCP Consulting revealed that 61 per cent of UK retailers believed Black Friday was unprofitable and unsustainable, up from 32 per cent in 2015.

Part of the reason is the high level of returns, with LCP Consulting’s analysis indicating that five million parcels purchased on Black Friday last year were returned, 50 per cent more than usual across the year as a whole.

“The true profit impact of Black Friday is not driven by sales increases and gross margin; it is driven by the additional operating cost and the complexity of managing operational peaks,” says LCP retail analyst Stuart Higgins.

Professor Bamfield agrees that Black Friday, which falls on November 24 this year, is not the bonanza that many UK retailers have been led to expect.

“There’s no evidence that it increases Christmas spend at all. There’s a focus on companies offering discounts, but no evidence that it improves profits; in fact, probably the opposite,” he says. “The problem is that customers now expect it, and retailers aren’t allowed to collaborate with each other and say ‘we’re killing ourselves’, so they really are stuck with it.”

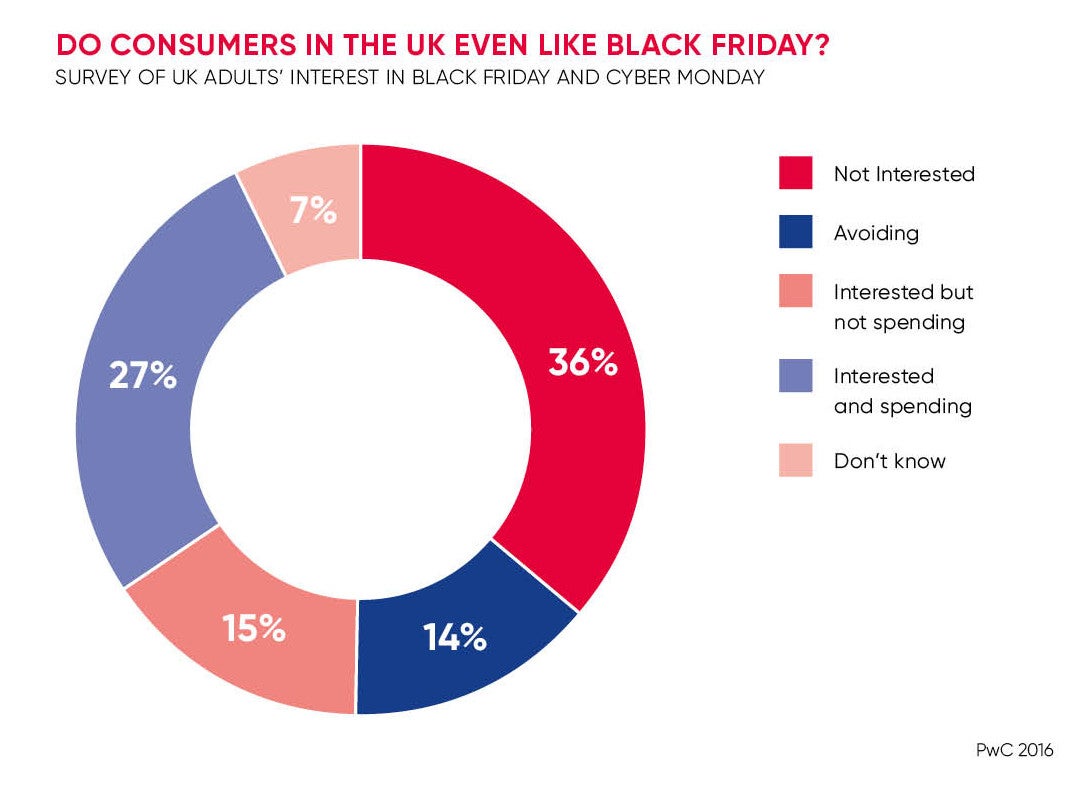

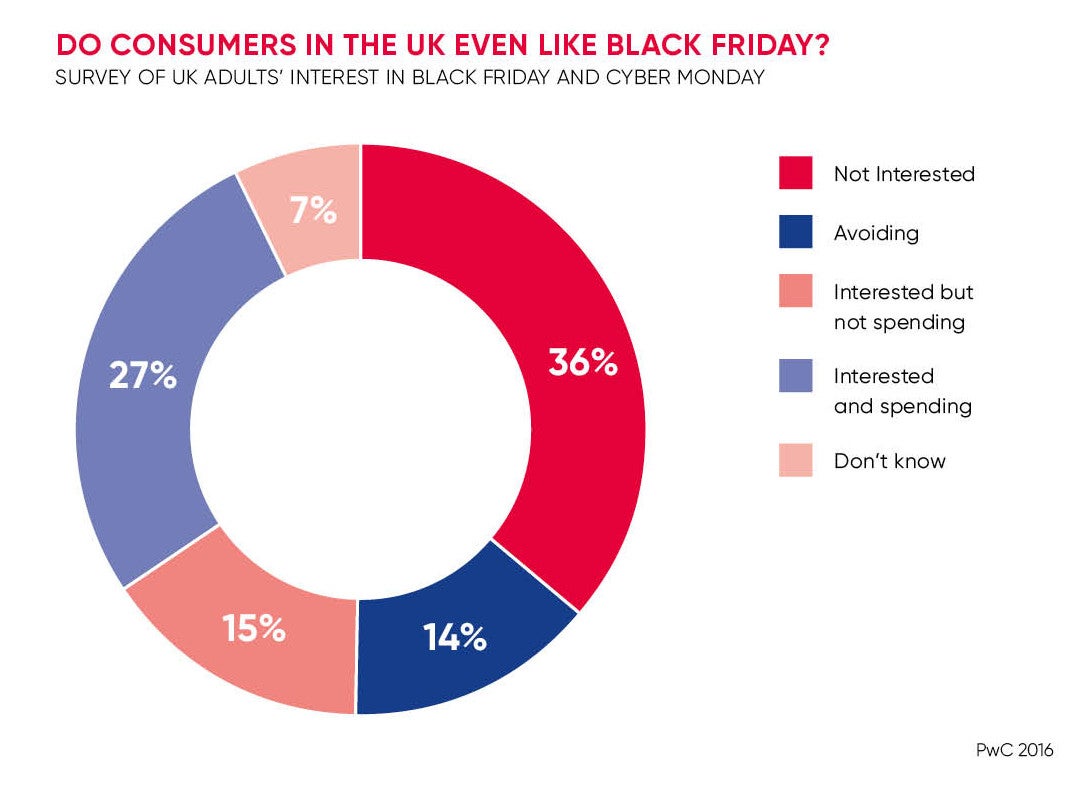

Ridiculously, there’s a fair bit of evidence that even customers don’t actually like Black Friday all that much. Last year, a survey conducted for PwC found that more than a third of Brits weren’t interested in Black Friday or Cyber Monday, with one in seven people saying they purposely avoided the events.

“Black Friday is very much a phenomenon for C2s, Ds and Es [socio-economic grades],” says Professor Bamfield. “I think that AB and C1s probably plan their Christmas longer in advance or don’t want to get caught up in the frenzy.”

This year, PwC believes there will be rather more enthusiasm for Black Friday, but it remains to be seen whether shoppers will actually follow through.

According to retail research firm Mintel, one in five people who browsed Black Friday offers last year didn’t actually end up buying anything, with more than a quarter of these people saying they didn’t believe the offers were really genuine. And of those who did, more than a third said they regretted their purchase, indicating they may be a bit more selective this year.

“It is likely that 2016 marked the peak for Black Friday shopping,” says Richard Perks, Mintel’s director of retail research. “Black Friday has been a major distorting factor in Christmas demand over the last few years and there are some signs of disillusionment creeping in.”

Retailers have got to get out of this, and they’re making it into a longer period and reducing the size of the discounts available

When US social media intelligence tracker Crimson Hexagon examined sentiment about Black Friday, it found that in 2010 only 20 per cent of social media posts were negative. By 2015, however, this proportion had doubled, with most conversations focused on “anger, sadness, fear and despair”.

“I think it was absolutely thrilling for the first couple of years; it combined the joys of shopping with the joys of a football match,” says Professor Bamfield. “But we send people round the shops on Black Friday, and it wasn’t as busy last year as it was in 2014 and 2015. I wonder whether consumers are fatigued by the whole thing.”

As a result, some retailers are now attempting to step away from Black Friday sales. Two years ago, for example, managing director of John Lewis Andy Street said he had concerns about the effects of Black Friday on profitability and expressed regret that it wasn’t possible to “put the genie back in the bottle”.

Asda, too, has stepped back from Black Friday, despite being one of the retailers that brought it to the UK in the first place, and now says it prefers to focus on good deals all year round.

Others are attempting to wean customers off Black Friday more subtly, by diluting the experience, says Professor Bamfield.

“A week before Black Friday, a lot of retailers say ‘why wait?’ and many offers on Black Friday are still available on Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday,” he says. “Retailers have got to get out of this, and they’re doing it by making it into a longer period and reducing the size of the discounts available.”