Fashion retailer River Island is attaching radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags to every item of clothing it stocks.

The tags enable a store’s staff to identify all items of clothing on the shop’s shelves and racks, and in stockrooms and fitting rooms, using a remote RFID reader. Just switch on the reader and it sends out radio waves which identify a unique code embedded in every tag. In just a few minutes, store managers can conduct a stock check and identify every item of stock in-store, a process that done manually takes many hours. The stores used to carry out a stock take just once or twice a year. Now they do it every week.

Jon Wright, River Island’s head of loss prevention and safety, says the technology is transforming the chain’s business, helping make sure the stock customers want is available in stores and online. The chain began testing RFID tags four years ago and is now rolling the technology out across 280 stores and its warehouses. “The main goal was to fix some of the stock accuracy issues in our business,” he says.

Jon Wright, River Island’s head of loss prevention and safety, says the technology is transforming the chain’s business, helping make sure the stock customers want is available in stores and online. The chain began testing RFID tags four years ago and is now rolling the technology out across 280 stores and its warehouses. “The main goal was to fix some of the stock accuracy issues in our business,” he says.

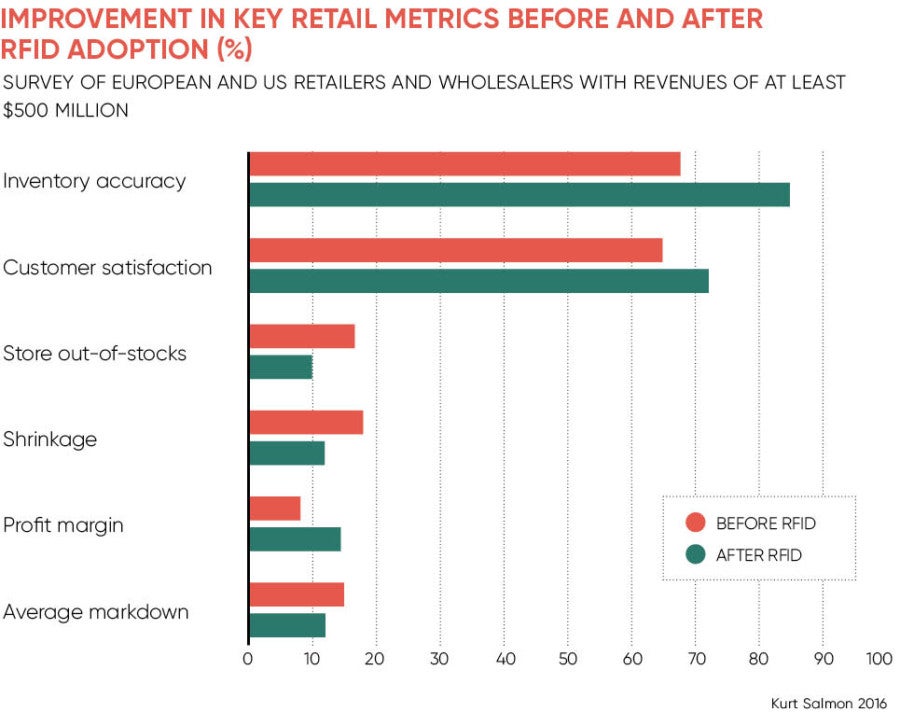

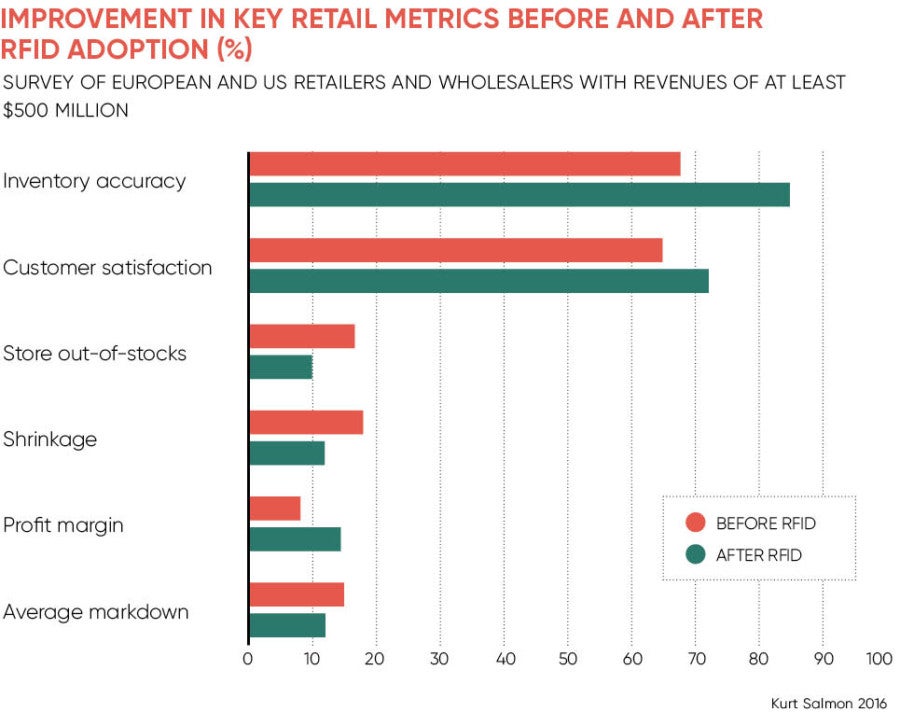

Mr Wright says stock accuracy – whether the stock in-store matches the retailer’s records – was typically about 70 per cent under the old manual stock-checking system. RFID tags enable the stores to check their stock continually and make sure they have the right lines on show. RFID technology has helped boost the stock accuracy figure to 98 per cent, he says. This in turn has helped boost store sales significantly as they are able to ensure the most popular lines are in stock.

Consumers are pushing the retailers to know what product they have and where they have it at any given moment

RFID tagging is a growing trend among clothes retailers as the cost of the tags comes down and the technology improves.

Along with River Island, other chains such as Marks & Spencer and John Lewis have tested the tags and are introducing them across their stores. US department giant Macy’s is launching the technology across its business. Tesco, Asda and many others are also getting involved.

RFID technology has been on offer to retailers for more than a decade, but is only just starting to catch on. One reason is the huge growth in shopping via mobiles, tablets, desktops, and even messaging services and social media. This has led to the growth of omnichannel retailing, having a single view of products and customers across all these shopping channels and warehouses. That forces retailers to have clear knowledge about where every individual piece of stock is situated in the supply chain. When a shopper orders an item, the chain can locate it and get it to a nearby store for them to pick up.

As Mr Wright says: “The consumer’s mindset has changed so much that they do not accept the product is not available when they want it. There is so much competition that they can get a pair of jeans anywhere. Consumers are pushing the retailers to know what product they have and where they have it at any given moment.”

Department store chain John Lewis has been experimenting with RFID for about ten years, and is now trialling the technology and introducing it to some 30 of its stores. Most of its fashion range will be RFID-enabled by the end of this year.

But this is not without its challenges, says Simon Russell, the chain’s director of retail operations development. He says implementing RFID is easier for retailers that sell their own branded stock as they control the entire supply chain, so can attach tags at source.

“If you are a department store like us and you are dealing with multiple brands, it is a lot more challenging to negotiate with every single supplier to ask if they would be willing to put the tags on at source or whether you need to have an ancillary distribution centre to be able to attach the tags,” he says. “We are gradually overcoming those challenges and I think RFID is having its coming of age – it is much more widespread among retailers.”

But Francisco Melo, leader of global RFID at Avery Dennison, warns: “RFID exposes the ugly.” By telling retailers where they are overstocked and understocked, it exposes their weaknesses. “Therefore, you have to be able to embrace that change, and adapt those processes and ways of working to do that,” he says.

More than 100 billion items of apparel are sold a year globally, while RFID tagging is in single percentage figures, so there is much room for expansion.

The key move which unleashed RFID was the creation of a single global standard, says Jacky Broomhead, UK market development manager for apparel at GS1, which creates supply chain standards for retailers. Before 2005, there was no single standard and retailers used a variety of tags. But the Electronic Product Code (EPC) was launched in 2005 and refined in 2008 as EPC Generation 2. “We got the industry to unite globally under a radio frequency for the tags to operate. The benefit is the tags will work anywhere in the world,” she says.

Having one standard reduces the price of the tags, which has come down by 75 per cent in the past five years. The cost varies by volume, but it was on average about 12p a tag and now retailers are getting them for 5p or 6p, says Ms Broomhead. The cost of implementing the hardware – buying the readers – is also relatively low.

RFID tags could have wide uses in the future, beyond just checking stock. They could replace bar codes for payment and act as security tags.

Jim Prewitt, vice president of retail industry strategy for North America at JDA, believes the use of the tags will spread beyond fashion into other areas of retail. “RFID is one piece in the broader adoption of internet of things devices, including sensors, beacons, cameras and smart shelves,” he says. “The combination of these technologies will drive adoption into more stock keeping unit-intensive retail sectors like grocery.”

The RFID industry will have to overcome the perception that this is a costly, complex technology which is hard to deliver. The experiences of retailers such as River Island and John Lewis suggest those perceptions are changing.