Natural disasters may be unavoidable, but they do not have to be overwhelming. Businesses are not doomed to suffer in the aftermath, so long as plans have been made to minimise the risks and manage the knock-on impacts as effectively as possible.

The huge challenges posed by Mother Nature should not be underestimated, however. As supply chain managers know all too well, an interconnected global economy means the financial consequences of any catastrophe ripple around the world very quickly.

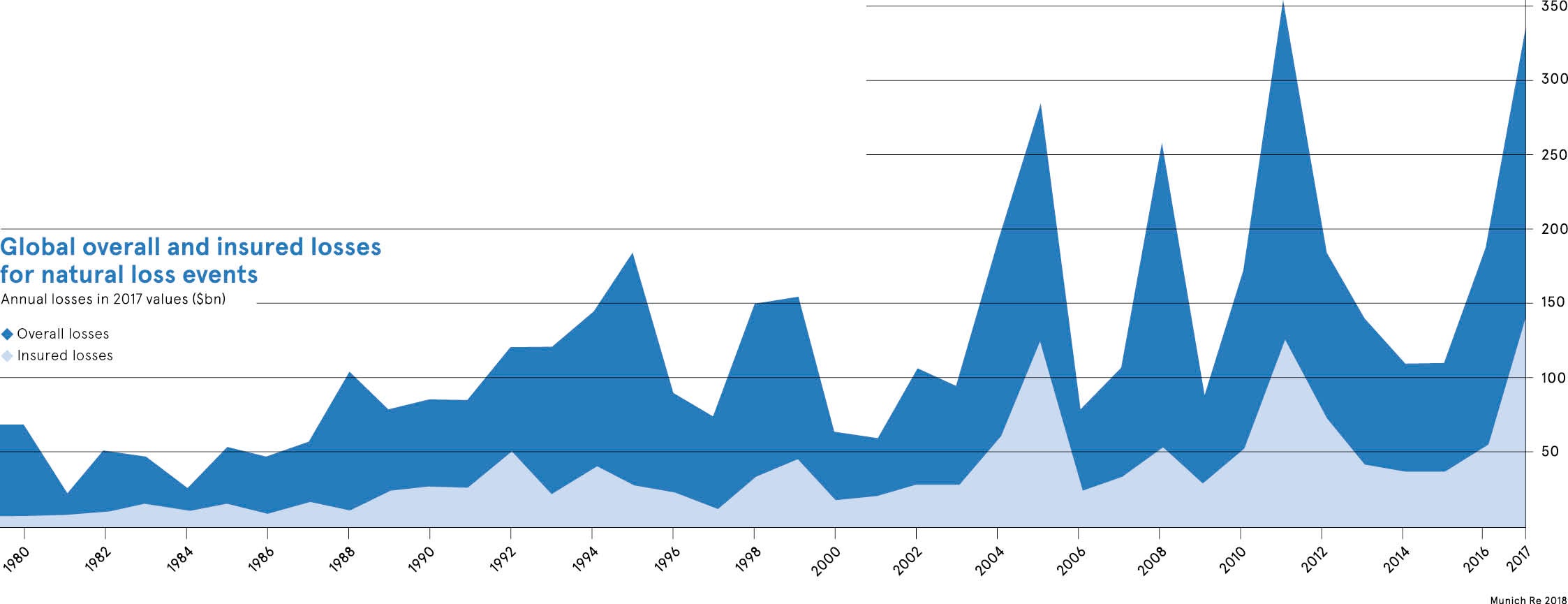

There is also growing concern about the increased frequency of extreme weather events. Reinsurer Munich Re says climate change could mean the fierce hurricanes in the Caribbean and United States, and severe flooding in South Asia during 2017 could be a “foretaste of the future”. The latest Allianz Risk Barometer puts natural catastrophes among the top three global business risks for 2018.

According to Munich Re’s annual review, natural disasters caused $330 billion (£231 billion) in overall losses last year. Such events often result in the interruption of supplies and can leave some companies unable to fulfil their commitments to customers, leading to subsequent losses in revenue and profit. There is also the danger of reputational damage. If a crisis is handled badly, it can mean a permanent loss of market share.

The stakes, then, are extremely high. So what can those in charge of supply chains learn from recent natural disasters? How might they utilise the latest risk management techniques and advances in technology to prepare much stronger contingency plans?

Catastrophes can sink those caught off guard, but a well-prepared company should feel confident about filling the void left by less nimble competitors

The US response to the hurricane season of 2017 offers plenty of good lessons. Across Texas, roads were badly flooded and the Port of Houston was closed for almost a week after Hurricane Harvey hit, causing major delays in shipments. The three category 4 hurricanes that swept across the Caribbean and America during September – Harvey, Irma and Maria – eventually caused $215 billion (£150 billion) in overall losses, according to Munich Re.

Yet given the enormous scale of these events, US businesses coped reasonably well because of detailed contingency plans. Many companies had arranged for alternative trucking and shipping routes, and managed to move materials, consumer goods and personnel before the worst of the weather hit.

Delivery giant UPS saw profits fall in the third quarter of 2017, partly as a result of problems caused by the hurricanes. The company sought to reassure customers it would be ready to withstand more such weather events in future, announcing major investment in storage capacity for 2018.

“Having excess capacity in place is an expensive decision, but companies have learnt how useful it can be,” says Dr Panos Kouvelis, director of the Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation at Washington University in St Louis. “I think businesses in the US have become better at anticipating and planning for hurricanes. Many companies were surprised by the magnitude of the impacts of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, but they have learnt a lot of lessons and have been building more resilience in the supply chain.”

Building resilience can involve big strategic decisions. If natural disasters remain a strong possibility in part of the world where key suppliers exist, companies may be wise to consider moving a proportion of their business to suppliers elsewhere. “With really critical products, even if it costs a bit more, it’s worth thinking about diversifying your suppliers that way,” says Professor Brian Squire, who leads the HPC Supply Chain Innovation Lab at the University of Bath School of Management.

Technology has given businesses tremendous opportunities to reduce risk. Advances in satellite imagery have supplied companies with more detailed weather forecasts and the chance to assess likely impacts on particular geographical locations. Data analytics and modelling software let supply chain managers see how a potential problem in one area affects every other aspect of the business.

“The modelling tools can help you to map out your supply chain vulnerabilities with incredible accuracy,” says Julia Graham, deputy chief executive and technical director at the Association of Insurance and Risk Managers (Airmic). “I see organisations doing incredibly sophisticated work these days, mapping dependencies and eventualities in great detail.”

The larger the business, the greater the need to think holistically about the supply chain. Digitisation can help fuse different aspects of a business together to make sure there are no gaps in information if a disaster should strike.

“When an organisation is small, everyone tends to know what’s going on,” says Suki Basi, chief executive of Russell Group, the risk management and software services company. “As it grows larger, there is a tendency for the left hand not to know what the right hand is doing. But technology can help larger organisations integrate operations and increase the speed of decision-making.”

Agility in a time of crisis can also depend on forging relationships with leading charities working on the ground. “Some of the NGOs are heavily involved in data analytics and they can help businesses understand what’s likely in the aftermath of an extreme event,” says Ms Graham. “Risk is more connected than ever before and if you want connected answers to risks, you have to be open to collaboration.”

The havoc wreaked by natural disasters might lead to some mutually beneficial partnerships, but the battle for customers never stops. Catastrophes can sink those caught off guard, but a well-prepared company should feel confident about filling the void left by less nimble competitors.