As the fourth industrial revolution, characterised by smart factories and digital manufacturing, makes its presence felt globally, there is an upsurge in handwringing about the notion that technology will eliminate human jobs.

Labour’s deputy leader Tom Watson has even launched a new commission to study the future of work and tackle fears about the rise of the machines. Yet these concerns aren’t new; they go back to the first Industrial Revolution some 250 years ago and the Canut revolts in France, as well as the Luddite resistance in Britain.

“Nowadays, people who worry about new technologies are often dismissed as living in the past. That would not be fair; such concerns must be addressed seriously,” Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund, said at a conference recently.

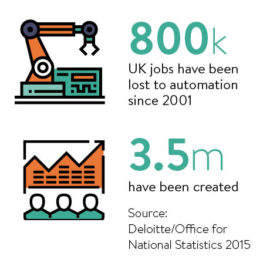

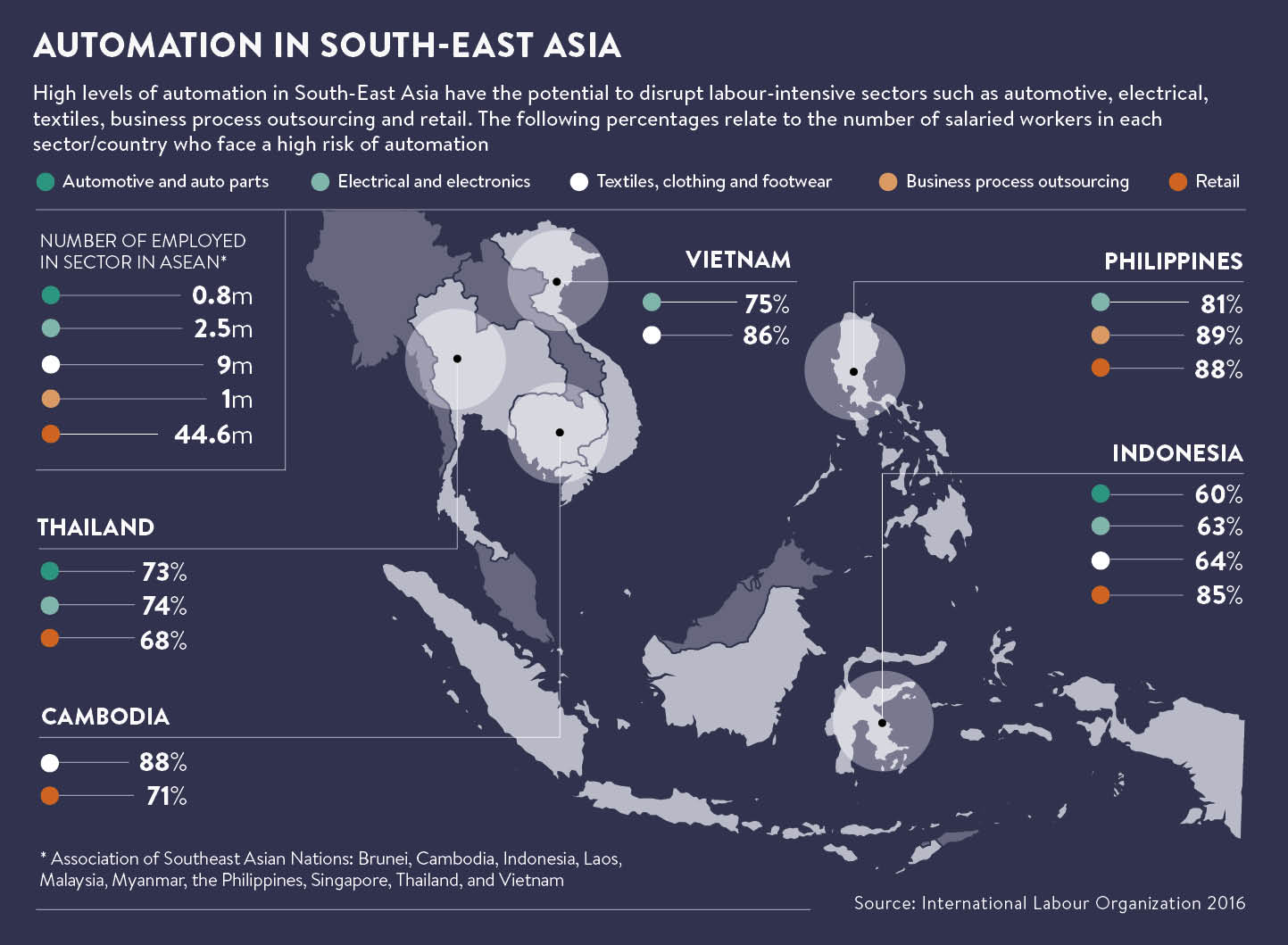

In the last 15 years, 800,000 British jobs have been automated, according to research by Deloitte. Roles as secretaries, counter clerks, filing clerks and travel agents have evaporated, largely due to advances in technology. A recent report from the International Labour Organization found that more than two-thirds of South-East Asia’s nine million textile jobs are also now under threat.

It’s been coined the Industrial Internet in the United States or Industry 4.0 in Germany. This new revolution in automation involves data exchange in cyber-physical systems, the internet of things and cloud computing. Manufacturing technologies communicate and co-operate with each other and with humans in real time, spearheaded by companies such as Siemens and General Electric.

Job losses

“One common fallacy is that machines are replacing people. The reality is that machines don’t work without humans. A more accurate description is that a large number of people are being replaced by a smaller number of people using machines, explains Thomas Frey, futurist and founder of the DaVinci Institute.

“One common fallacy is that machines are replacing people. The reality is that machines don’t work without humans. A more accurate description is that a large number of people are being replaced by a smaller number of people using machines, explains Thomas Frey, futurist and founder of the DaVinci Institute.

Visit a garment factory in Indonesia producing adidas sports products and you’ll see that cutting fabric is a tedious and time-consuming task. Now the company plans to slash manual labour for its cutting processes to 30 per cent. Some factories in Cambodia have already ditched cutting by human hand altogether; the heyday of the Asian sweatshop is over.

Globally, the jobs that have disappeared are concentrated in the clerical, administrative and retail sectors, as well as in low-skilled manufacturing. Any ex-checkout operator or junior lawyer will tell you that a computer in the form an automated, self-service till or document auto-scanner is more cost effective than a human.

Transport, distribution, hotel and food services are now in line for an automaton makeover; routine human work is disappearing very quickly and never coming back.

“From a technology point of view, 35 per cent of today’s jobs are highly automatable in the next ten to twenty years,” says Angus Knowles-Cutler, vice chairman at Deloitte.

If the cost of labour rises with inflation and with the implementation of the national living wage, automation is likely to accelerate this process. “If the availability of qualified labour is reduced as the UK leaves the EU, then jobs that have traditionally been done by migrants are as likely to go to machines as to British workers,” says Mr Knowles-Cutler.

Are we facing a global jobless crisis?

A few years ago Mr Frey predicted that over two billion jobs will disappear by 2030, roughly 50 per cent of all the workers on the planet. Yet this frightening prospect of job annihilation is only part of the picture.

“It does not necessarily mean that the workforce become totally redundant and replaced. More accurately it means the skillsets change in the workforce to support the replacement technology,” says Roger O’Brien, director at the Institute for Automotive and Manufacturing Advanced Practice, University of Sunderland.

“If you consider the third industrial revolution, which happened with digital technologies and electronics from the late-1960s onwards, robots started to become commonplace in factories, then new skills where required by workers in order to program and maintain them effectively.”

There’s an increasing positive belief among industrialists that technology has the potential to extend human capability, not curtail it

If you look at economies such as South Korea, Japan and Germany, where there is the highest utilisation of robots and automation, you can observe some of the lowest unemployment rates. These countries show that embracing the latest technology smartly can create new jobs.

“Roughly 65 per cent of today’s jobs in the US are information jobs that didn’t exist 25 years ago and we keep increasing the sophistication of jobs as we improve our overall intelligence,” says Mr Frey.

In the not too distant future we can expect courier drivers to retrain as drone pilots, Indonesian fabric cutters to reskill as 3D printer managers and car production line fitters to become robot operators. There’s an increasing positive belief among industrialists that technology has the potential to extend human capability, not curtail it.

Job vs work

There is also recognition that there’s a difference between jobs and work. Work will always be there; it’s the jobs that change in an industrial revolution. “The UK has a great history of creating new jobs faster than the ones being destroyed by technology,” says Mr Knowles-Cutler.

“Compare those 800,000 jobs displaced by automation to the 3.5 million new jobs that have been created to replace them in the creative, technology, business services and caring sectors. The good news is that that the new jobs pay around £10,000 more a year than the ones that have gone, adding about £140 billion to the British economy.”

There’s also no resting on our laurels as humans. If you have managed to upskill from the factory floor and on to an office computer thinking your job is safe, think again. The hundreds of millions of so-called knowledge workers around the globe are now threatened with automation. Artificial intelligence and machine-learning are in the process of automating tasks that rely on subtle judgments, analysis and creative problem-solving.

“The next economic sector to be disrupted will be the automation of professional and public services, and regular, routine office work in companies,” says Professor Birgitte Andersen, chief executive of the Big Innovation Centre. “We need to embrace change and not pretend it’s not happening. The winners are those who can adjust fast. History has shown this again and again.”

The awareness of both the possibilities and threats of technology and automation in the workplace is fast moving up government agendas around the world. Continually investing in education, training and skills was the most important response to each industrial revolution. It’s no different today.

“The UK is actually one of the best positioned major economies in the world to not only cope with technological advances, but also profit from them,” says Mr Knowles-Cutler.

“The main building blocks are there – one of the highest graduate or equivalent level workforces, a disproportionate number of world-beating universities and research centres, leadership in a wide range of high-skill service sectors and a flexible labour market.”

The question is how can us humans future-proof ourselves in the great technology takeover of the global labour market? The answer lies in two words – being human. The skills and attributes that make us human and not robotic will be the ones in most demand.

“In the future, those who are highly adaptable will rise to the top,” says Mr Frey. As automation eats into each new business role and creates new ones, we can expect to reskill a number of times during our careers. Uniquely human skills, such as critical thinking, personal service, comprehension and expression, are likely to remain in great demand.

Job losses