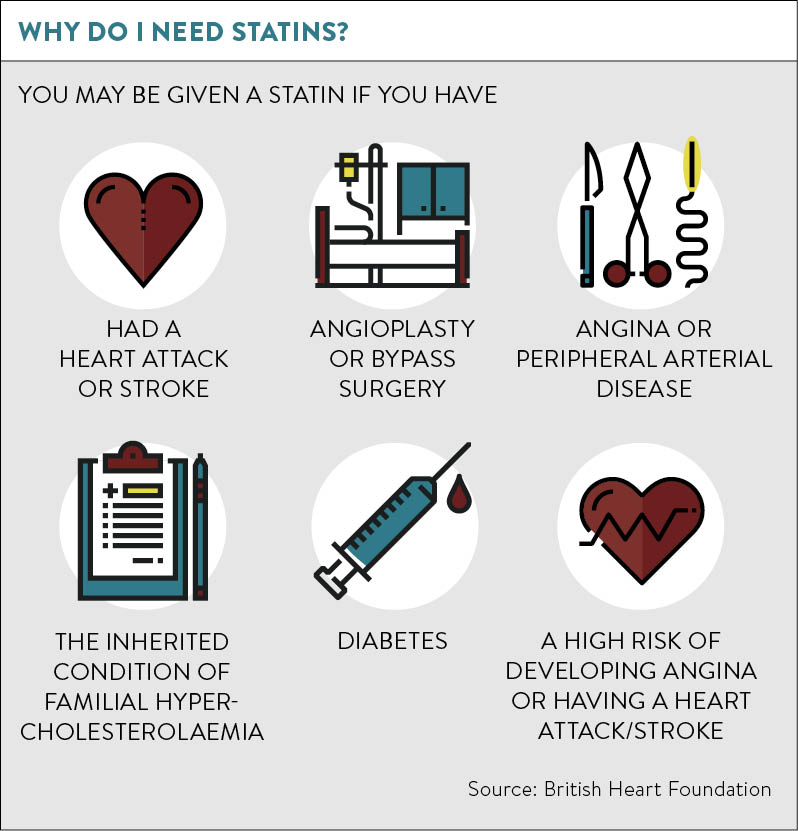

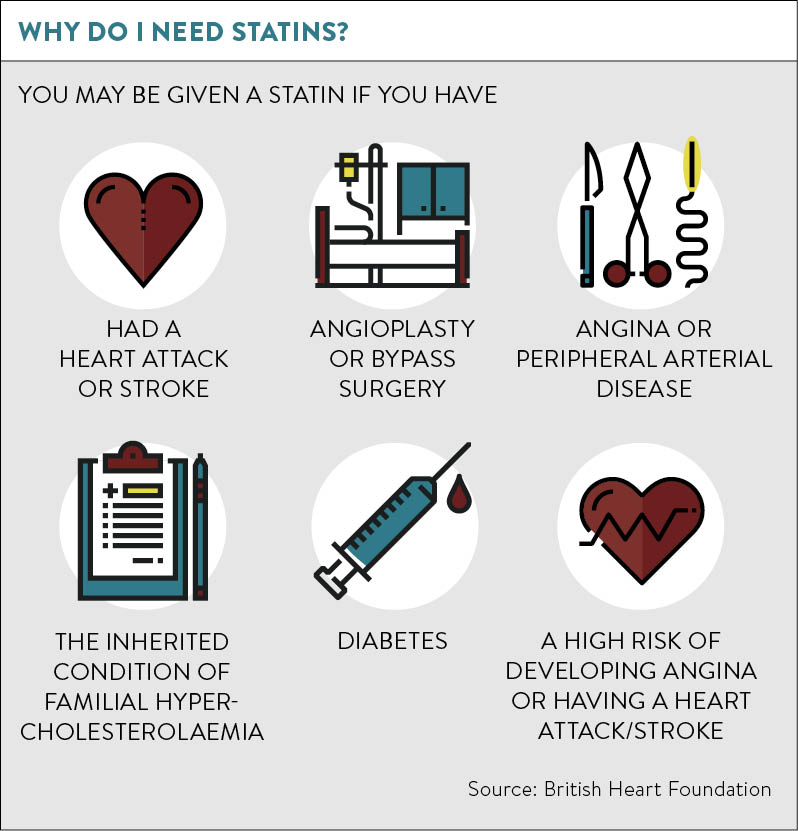

Few drugs have been tested as comprehensively as statins. Trials involving hundreds of thousands of people have shown that even those with no history of heart disease can cut their risk of a heart attack or stroke by 20 per cent if they take statins. And since heart attacks and strokes account for a third of all deaths, the overall benefits are huge – in the UK, statins are reckoned to save 9,000 lives a year.

Yet every day, people who have been prescribed statins by their GPs give them up. This even applies to people who have had a stroke, says Peter Sever, professor of clinical pharmacology at Imperial College London. “These are patients who have had a stroke, recovered the use of their limbs and been prescribed a statin because it reduces their risk of a second stroke by 25 per cent,” he says. “Yet within a year, 80 per cent of them are no longer taking it – that is a terrible statistic.”

Understanding why so many people give up a potentially life-saving drug is a conundrum that puzzles those like Professor Sever who have been involved in the trials. “It’s easy to blame the patients for not listening to what we tell them, but sometimes we don’t tell them the right things,” he says.

“Some physicians and specialists are actually not very good at explaining these things. Stroke patients are treated by neurologists then sent home to the care of their GPs and some are just not focused enough on the need for these people to stay on statins for the rest of their lives.”

“Some physicians and specialists are actually not very good at explaining these things. Stroke patients are treated by neurologists then sent home to the care of their GPs and some are just not focused enough on the need for these people to stay on statins for the rest of their lives.”

From the perspective of the trialists, it’s an open-and-shut case. Some have become very critical of any countervailing views, says Sir Rory Collins, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the Clinical Trial Service Unit within the University of Oxford, comparing those who cast doubt on statins as being as irresponsible as those who put children at risk by falsely claiming a link between MMR vaccine and autism.

Influenced by studies

Sir Rory and Professor Sever are among the authors of a new review of the evidence, published earlier this month in The Lancet. This argues that patients and some doctors have been overly influenced by studies linking statins to muscle pains, when the gold standard of evidence, from randomised controlled trials, shows no such link. Launching the review on September 7, Sir Rory said he had complete confidence from the trial evidence that muscle pain was a rare consequence of taking statins.

Publication in The BMJ of two papers that made erroneous claims about the frequency of side effects of statins was a serious disservice to British and international medicine, far worse in the harm done than the MMR scare, he says.

In this high-stakes statins war, proponents battle for the moral high ground. The evidence of benefit may be clear, but many doctors baulk at the proposition that millions of healthy people should be prescribed drugs to protect against diseases they do not yet have and may never get.

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that anybody with a greater than 10 per cent risk of developing cardiovascular disease within the next ten years should be offered statins has been ignored by many GPs. “There should be no automatic prescribing based on slavish devotion to a simplistic mathematical model of risk,” according to Dr Andrew Green of the British Medical Association in October 2014.

Side effect debate

Even more hotly-contested is the issue of side effects. The trials paint an attractive picture, with serious adverse effects being extremely rare, and that is borne out by experience. But patients with more modest side effects such as muscle pain turn up much more often in GPs’ waiting rooms than the trials predict. A recent high-profile casualty was Sir David Nicholson, former chief executive of the NHS, who said in July that he had given up taking statins.

The trials show there is a very small increase in the risks of muscle problems, but it’s absolutely tiny when you look at it in an entirely objective way

Sir David told The Sunday Times: “I was getting muscle and joint pain. It was getting worse and worse. It was mild to begin with and I kind of thought it was because I was getting old. I stopped taking them for a week and I got better.”

His experience perfectly matches that of many people and suggests evidence of minor but debilitating side effects has been missed. Those who carried out the trials deny flatly that this is possible.

“The trials show there is a very small increase in the risks of muscle problems, but it’s absolutely tiny when you look at it in an entirely objective way,” says Professor Sever. The chance of anyone getting muscle problems was between one in a thousand and one in ten thousand – and that was true whether they were taking the drug or taking a placebo.”

He was a chief investigator in the Anglo-Scandinavian Coronary Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) , a part of which was stopped early after three-and-a-half years because the emerging benefits of statins were so great it would have been unethical to continue offering half the participants placebo pills.

“But when we stopped we said to them we are going to offer you statins until the original planned end of the trial, another two-and-a-half years,” says Professor Sever. “About two thirds said yes, and they were all followed up in the same way. Every time they came to the clinic they were asked how they were, had they had any side effects. In the blinded part of the trial – when people didn’t know if they were getting a statin or a placebo – we couldn’t detect any excess muscle problems. But as soon as they knew they were taking a statin, there was a 40 per cent increase in complaints of muscle-related symptoms.”

All that had changed was that participants now knew they were taking a statin, when earlier they hadn’t. “It’s not exactly rocket science to deduce that complaints increased because there has been such intense media publicity about statin-related issues,” he says.

[embed_related]

Many doctors blame newspapers and TV, but the media did not invent the issue. Plenty of studies have been published in the medical literature that show higher rates of side effects than in the trials, but they use less reliable methods. It was one of these observational studies that led to The BMJ reporting in two articles that 18 to 20 per cent of statin-takers suffered side effects, claims since withdrawn because the original study that made them did not prove cause and effect. The problems it found were not imaginary and occurred while people were on statins, but the drug and the side effects could not be unequivocally linked.

Publication in The BMJ and the resultant publicity led to an 11 to 12 per cent rise in people giving up statins in the UK, a study later showed, which could result in 2,000 heart-attack or stroke deaths over the next ten years that otherwise might have been avoided. Sir Rory warns: “The impact worldwide, given the international readership of The BMJ, may well be far greater.”

Patients buffeted about in this war of words may well wonder what they should do, especially if they look at the information leaflet in their pack of statins and read that common side effects such as muscle pain “may affect between one in ten and one in a hundred patients”. If the manufacturers say risks are that common, why should patients believe the trialists who say they are 100 times less likely? Are these leaflets wrong? “Yes, there is a need to review the kind of information provided to patients,” Sir Rory concludes.

HOW DO STATINS WORK?

Statins lower cholesterol, a naturally occurring waxy substance that circulates in the blood. It is made by the body, particularly the liver, but also occurs in food. People with higher levels of cholesterol are more prone to heart disease, so efforts over decades were devoted to finding drugs to lower cholesterol. Many were tested and did indeed lower cholesterol, but had little or no effect on death rates.

Statins were the breakthrough. But since earlier cholesterol-lowering drugs didn’t work, some experts believe that statins have other effects that may be equally important – stabilising the “plaques” that form in the arteries from excess cholesterol and preventing them from breaking away to block the flow of blood. Statins may also reduce levels of inflammation. Be that as it may, doctors still work on the assumption that lowering cholesterol is the key.

Statins were the breakthrough. But since earlier cholesterol-lowering drugs didn’t work, some experts believe that statins have other effects that may be equally important – stabilising the “plaques” that form in the arteries from excess cholesterol and preventing them from breaking away to block the flow of blood. Statins may also reduce levels of inflammation. Be that as it may, doctors still work on the assumption that lowering cholesterol is the key.

Other drugs exist for those who have high cholesterol levels, but cannot tolerate statins. Ezetimibe (Ezetrol) may be used on its own or in conjunction with statins. Evidence shows that when used with a statin it does add some value, but at considerable cost. It is used mainly for patients with inherited high cholesterol levels.

A new group of drugs, the PCSK9 inhibitors, are causing a lot of excitement. They are biological agents (monoclonal antibodies) which target a protein in the liver called proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) and greatly reduce levels of the harmful form of cholesterol.

Trials show they are powerful cholesterol-lowering drugs and, more importantly, there is early evidence that they reduce heart attacks or the development of heart failure. Two PCSK9 inhibitors are licensed in the UK, alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha). The disadvantage is that they are expensive, at £4,000 per patient a year, and have to be given by Injection every two or four weeks. NICE recommends their use only for a small group at extremely high risk and even then only after the manufacturers agreed to a price cut.

Influenced by studies

Side effect debate