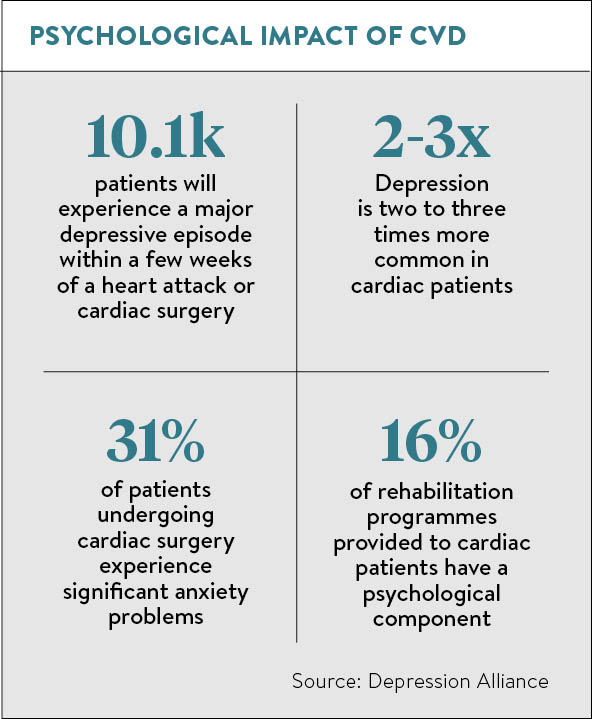

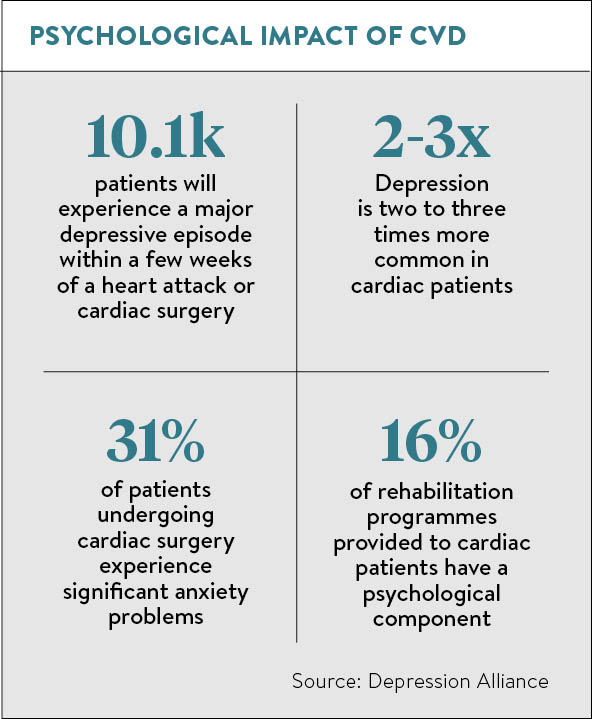

You might imagine that recovering from cardiac surgery or a heart attack would bring feelings of relief, perhaps even elation. Yet almost one in five patients will experience a major depressive episode within a few weeks. And a further 25 per cent of patients will experience minor depression or elevated levels of depressive symptoms, according to the charity Depression Alliance.

You may even be more likely to have a second heart attack if you are suffering from depression, says Andrew Steptoe, British Heart Foundation professor of psychology at University College London. “There is thought to be around a twofold risk [in those people] of having another heart attack or dying of heart disease, and there’s a lot of concern at the moment as to how that link takes place and what we can do about it.”

Dr Mike Knapton, associate medical director at the British Heart Foundation (BHF), says: “It’s a significant problem. There is evidence to suggest if you suffer from mental health problems, you are more likely to suffer cardiovascular disease (CVD), but there is also an increased risk of depression and anxiety following a cardiac event and surgery.”

Quality of life

In simple terms, that depression may be linked to being told you have a life-threatening condition. “But it may also limit your quality of life as can some drugs, such as beta blockers, which have side effects such as tiredness,” he says.

“Cardiac rehabilitation, including psychological rehab, is one of the most important aspects of the treatment pathway. But there is no point in saving lives if you can’t give a quality of life worth living.”

Yet, according to Depression Alliance, figures show that while 42 per cent of cardiac patients are currently provided with rehabilitation, only 16 per cent of these programmes have a psychological component, despite 31 per cent of patients experiencing significant anxiety problems and 19 per cent having depression. The charity warned in its 2012 report Twice as Likely that cardiac patients who are struggling with depression are linked with greater use of health services, poor quality of life and less successful rehabilitation.

Part of the problem may lie in the often acute onset of the condition. Patients whose CVD is diagnosed by a GP and who have already manifested symptoms of depression can be monitored. But, notes Tim Graham, consultant cardiothoracic surgeon at Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham and a council member of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh: “If a patient enters the pathway through an emergency route, much less is known and often in critical cases speaking to family members can be helpful.”

Either way, Mr Graham says: “If depression is suspected, the patient and their family are consulted at length and advised of the potential for the surgery to possibly make the condition worse. Patients also may be on a range of antidepressant medication all of which need careful monitoring during and after surgery as the surgery can affect the levels of these drugs adversely.

“We know that any patient who has surgery under anaesthetic has an increased potential to develop post-operative depression. Cardiac surgery is major surgery which therefore impacts on the potential for this, as well as the usually extended stay in intensive care. We also know that post-operative pain can lead to anxiety or depression, so pain management is a key aspect post-operatively.”

Psychological intervention

How can this be improved? An independent Cochrane Systematic Review points out observational data suggests psychological interventions, either alone or in combination with exercise and education, reduces depression in adults with heart failure. It also suggests that as previous studies have shown exercise improves mood and reduces weight, plus a reduction in depression improves compliance with medication and reduces behavioural risk factors for CVD.

Research comparing the benefits of psychological intervention alone, with comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation, including psychological intervention and/or usual care to identify which component is most important, is overdue.

That information might come from BHF-funded research. Professor Steptoe is involved in detailed lab work looking at the biological processes through which psychological factors might influence heart disease risk. His team is also carrying out clinical studies of people who have experienced a heart attack or had cardiac surgery and the emotional aspects of those experiences.

Dr Peter Brown, 56, a GP and father of four from Plymouth, suffered depression and anxiety for 12 months following emergency seven-hour bypass surgery three years ago. He says: “My father had undergone bypass surgery at 53 and died 11 years later from a massive heart attack the night before he was due to have further cardiac operations. So I was worried before and after surgery.

“It began to feel like a Sword of Damocles was dangling over my head, which wasn’t helped when one of the bypass grafts failed six months later and I was rushed to hospital to get a stent fitted.

“The cardiologist told me it was bad luck, but I became depressed and anxious. I’d think, ‘am I going to die tonight? Will I see my children grow up?’ You try and concentrate on the positives, but it is scary.”

But with support at home from his family, from nurses who taught him an exercise regime and then showed him via heart rate monitors that it was working, and sessions with a specialist cardiac psychologist, Dr Brown began to feel he had recovered after about 12 months.

“You have to build up your confidence slowly,” he says. “I used to get nightmares of boats sinking, cars crashing. But anxieties must be treated as much as physical symptoms – you have to address these fears.”

TREATING THE WHOLE PATIENT

Part of all surgeons’ training focuses on cardiothoracic surgery, says Tim Graham, consultant cardiothoracic surgeon at Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham and a council member of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd).

“As well as having training in the ‘nuts and bolts’ of the surgery, there is also now an additional part of the syllabus which trains the surgeons in ‘human factors’ including how people behave and react to surgery. This is becoming increasingly important, and many courses and toolkits are being put in place by the RCSEd to improve this aspect of training, including the recognition and management of mental health.”

“As well as having training in the ‘nuts and bolts’ of the surgery, there is also now an additional part of the syllabus which trains the surgeons in ‘human factors’ including how people behave and react to surgery. This is becoming increasingly important, and many courses and toolkits are being put in place by the RCSEd to improve this aspect of training, including the recognition and management of mental health.”

After surgery, the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR) has established standards of care which include psychosocial health. For this it recommends comprehensive, holistic assessment of patients as crucial, suggesting individuals with clinical levels of anxiety or depression should have access to appropriately trained psychological practitioners.

Moreover, the standards, which were set in 2012, suggest NHS services help patients develop awareness of ways in which psychological factors affect physical health, including perceptions of illness, stress awareness and development of stress management skills.

The BACPR standards confirm the importance of social support as social isolation or lack of social support is associated with increased mortality, whereas overprotection may adversely affect quality of life, and it notes the value of an agreed referral pathway to provide support and advice.

Dr Peter Brown, a Plymouth GP who suffered prolonged depression and anxiety after heart surgery, would like to see that pathway made more like those set out for cancer cases.

“Training is not good enough among cardiologists and surgeons,” he says. “The specialist nurses are excellent, but funding only allows three or four visits, which is inadequate. I think everyone should see a psychologist, even those patients who may be resistant. The psychological aspect holds back the physical recovery. If you are wound up, you can’t do your physical rehab properly. You need to get both right to make a good recovery.”

Quality of life